The real question on China’s new Arctic policy will be how the Arctic responds

ANALYSIS: How will the governments, institutions and people of the Arctic react to China's bid for influence in the region?

So, finally, it is official. China is a “Near-Arctic State,” according to itself. One with great plans, ambitions and the wealth to back them in the Arctic. We knew that, but now confirmation is calmly chiseled into China’s first official Arctic strategy, conveniently published in both Mandarin and English on Friday, inclusive of wide clarifications. Most compelling is a preambular paragraph that must have Arctic governments scratching their heads: “The Arctic situation now goes beyond its original inter-Arctic States or regional nature, having a vital bearing on the interests of States outside the region and the interests of the international community as a whole, as well as on the survival, the development, and the shared future for mankind. It is an issue with global implications and international impacts.”

Vital bearing on the survival of mankind! Make no mistake; the Arctic is no small matter to China, and the government in Beijing naturally wants its hand on the wheel to the extent possible.

[A ‘polar silk road’ forms the core of China’s first Arctic policy]

In the measured 5,500-word document China emphasizes its commitment to existing power-sharing structures in the Arctic, the sovereignty of the Arctic States, the Arctic Council and so forth. There are no comparing here, as there has been in past Chinese observations, the Arctic to the moon or other reference to the Arctic as a global commons. (At first back then, I found the moon-reference somewhat odd, but China, of course, had point: In 1979, the world adopted “The Moon Treaty” stipulating our collective ownership to such stellar entities).

China will not rock the Arctic boat per se, but it will, as we have long seen in real life, vigorously pursue its interests through any and all legal channels. Interestingly, the strategy even stresses the role of China as a one of the maintainers of peace in the Arctic, since China is a permanent member of the UN Security Council.

China’s Arctic interests are essentially unlimited: Climate change will affect China’s ability to feed itself, sea level rise will threaten densely populated coastal regions and of course, China wants its share of the riches: Oil, gas, minerals, fish, shipping, tourism, subsea-mining, Arctic enzymes, scientific data etc. The strategy confirms how China has already included the Arctic in its colossal Belt and Road Initiative aimed to embed China’s economy ever deeper into that of Southeast Asia, Central Asia, Africa and Europe through investments in new infrastructure — harbors, roads, railroads, terminals etc.

[How to read China’s newly released Arctic policy]

The interesting scenes to watch for, however, will not be those in which China’s unsurprising quest for influence and resources unfold. The real story is how the governments, peoples and businesses of the Arctic will respond.

Bottom line is that China brings a very different approach to governance and democracy to the Arctic (leaving, for a brief second, Russia out). That is what causes worry and unease. There is no free speech in China. Dissenting lawyers, writers and others are routinely arrested. There are few of the checks and balances on China’s leaders that the Arctic nations — again setting aside Russia for the moment — take for granted. So of course many in less authoritarian Arctic communities worry that China’s Arctic endeavors will slowly undermine democracy, open debate, accountability and transparency.

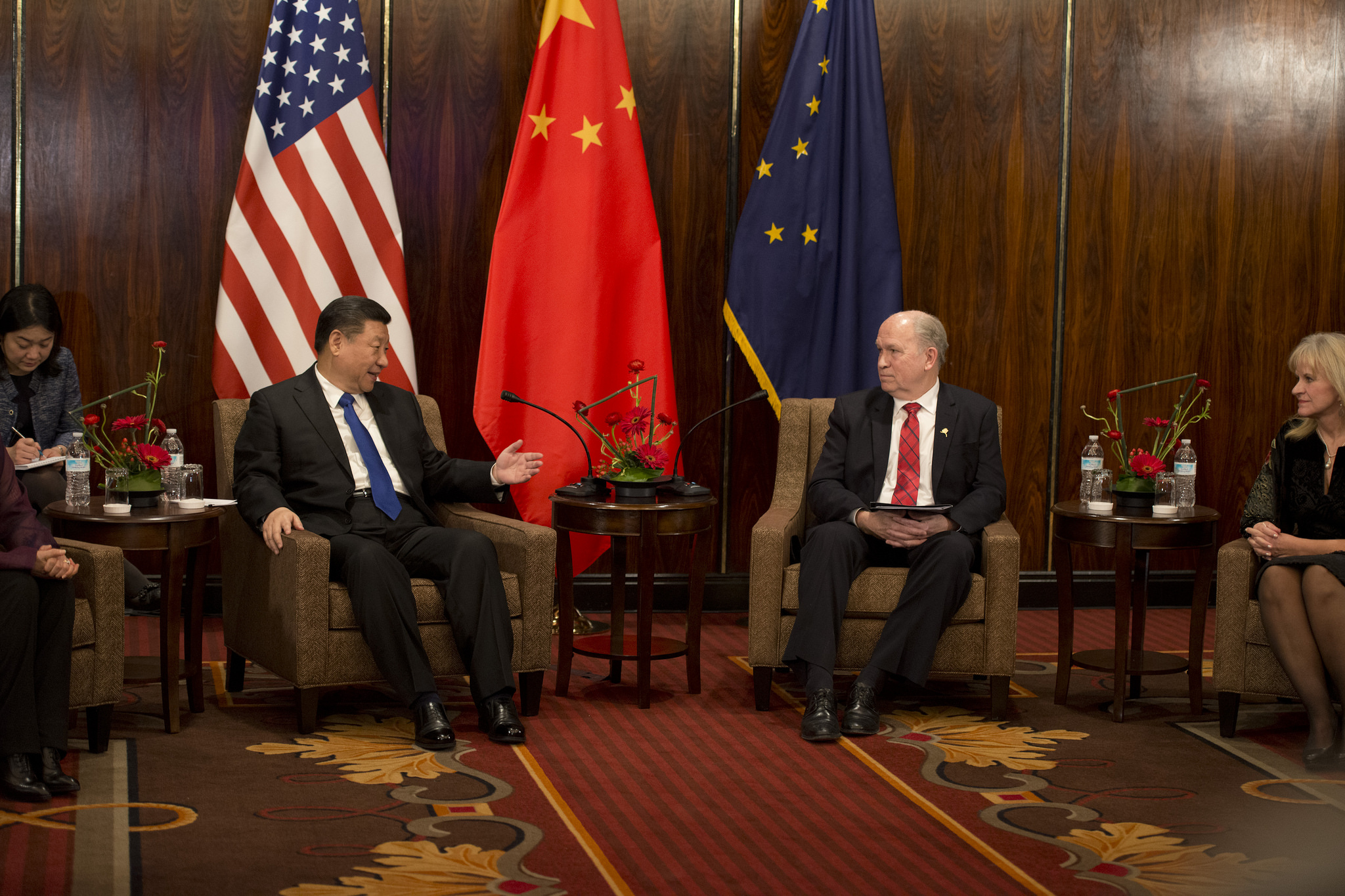

We are all familiar with the trend. I think, for instance, of the governor of Alaska, Bill Walker, who, in April last year, eagerly shook hands with China’s president Xi Jinping. The president was on a refueling stop on his way home from a visit to the U.S. Some months later in Beijing, Bill Walker signed deals that involved China’s oil giant, Sinopec, China Investment Corp. and the Bank of China in a multibillion dollar project to bring natural gas from Alaska to Asia; a project that U.S. investors had reportedly walked away from. I would trust Gov. Walker’s ability to write a fine speech on the disregard for human rights in China with his left hand in less than 12 minutes, and to deliver it at any high school in Anchorage or Fairbanks with conviction. But I do not expect that he will do so, simply because it could be bad for business.

Such accommodation is no longer news and certainly not unique to Alaska. What is really attention-grabbing is the speed with which this bonding with China is becoming a mainstay in the Arctic. China’s willingness to finance huge industrial projects and infrastructure is so tempting that none of the Arctic governments will want to lose out. Even super-rich Norway has adjusted. After 50 years with a hugely successful oil-and-gas sector, Norway commands the largest sovereign wealth fund in the world, holding a staggering $1 trillion and growing by the hour. In 2010 Norway awarded the Nobel Peace Prize to Liu Xiaobo, a Chinese human rights advocate. Then, in 2016, after years of being stonewalled by China and losing business, Norway signed an agreement with China promising basically, if not explicitly, never to do it again.

Norway is now pursuing Arctic cooperation with China at full speed.

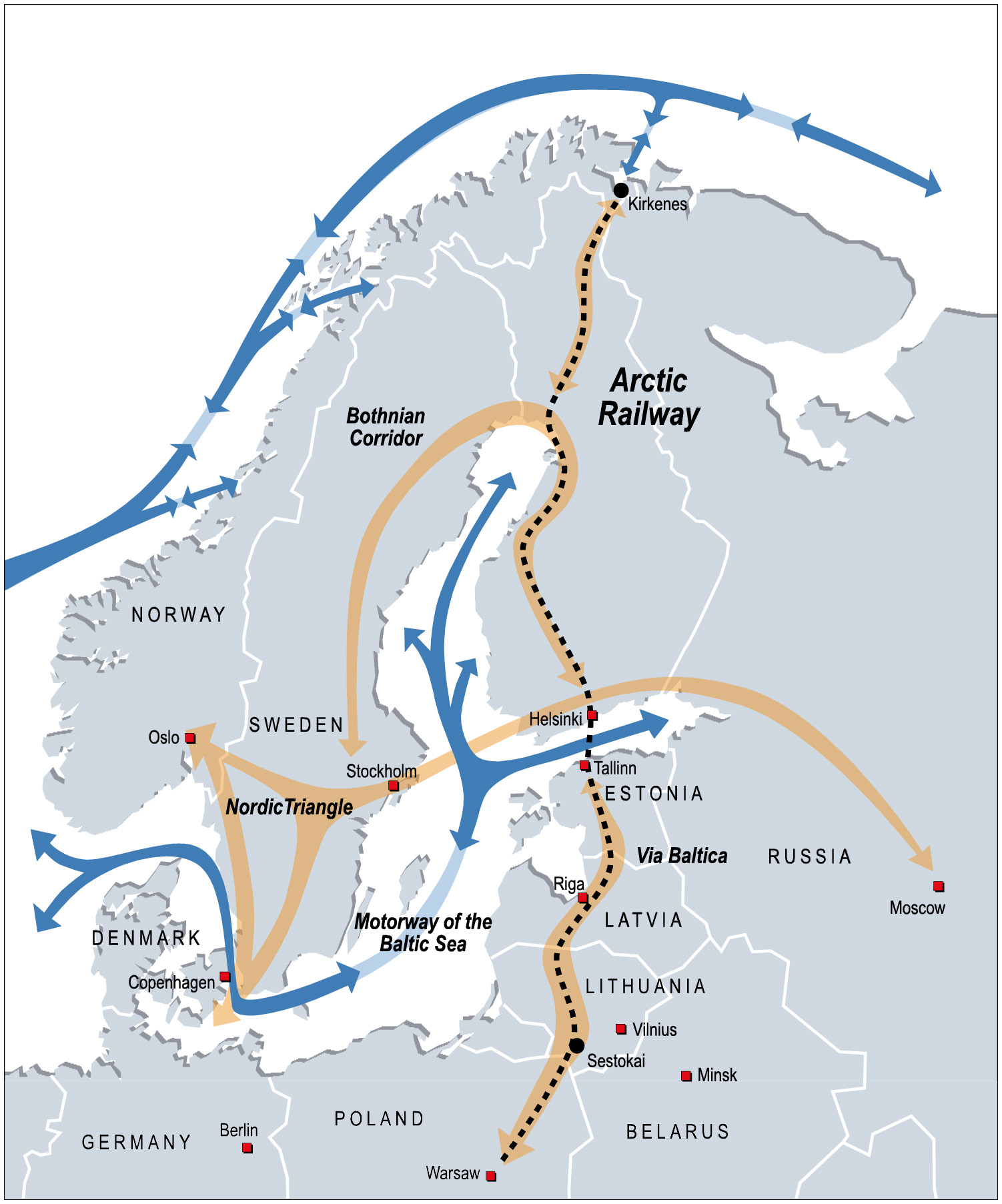

Finland has welcomed large Chinese investments in its Arctic Lapland region for some time. Several billion Euro are financing a new biodiesel and a bio-pulp plant; other Chinese investments fuel a local boom in tourism. Finland now wants to link up to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, hoping for Chinese financing of a railroad, the Arctic Corridor, all the way from Norway’s harbor in Kirkenes, the closest port to Asia in the Scandinavian Arctic, down through Finland and through an 80 kilometer tunnel to Estonia — forging, as we heard at the Arctic Frontiers conference in Tromsø last week, a corridor all the way from the Arctic Ocean to central Europe.

Do not be surprised if Finland becomes the first Arctic state to officially sign on to the Belt and Road Initiative — just shortly before Iceland jumps on board. Already in 2013, Iceland signed a free trade agreement with China, the first European nation to do so. China helped Iceland, when that nation was in dire financial woes in 2008. When former premier Wen Jiabao toured Europe in 2012, his first stop was a three-day tour de force in Iceland. The leaders in Reykjavik hope to one day be the Singapore of the Arctic, servicing, fueling and supplying Chinese and other freighters plying polar cargo-routes. Likewise, in semi-autonomous Greenland hopes are linked to China. Greenland’s premier, Kim Kielsen, head of the Self-Rule government in Nuuk, toured China in late 2017 scouting for investors for Greenland’s emerging mining sector. Chinese mining conglomerates already have stakes in potentially large operations in Greenland, aiming for zinc, uranium, iron-ore and rare earths. Russia, of course, has long enjoyed multi-billion Chinese investments in its Arctic province of Yamal. A 30-year deal, signed in 2014 by the presidents Xi Jingping and Vladimir Putin, exchanged Chinese funds and technical input for promises of LNG, delivered by sea or through a trans-Siberian pipeline to China now under construction.

As Mead Treadwell, former Lieutenant Governor of Alaska and former Chair of the U.S. Arctic Research Commission, explained to me in Iceland last year, China’s Arctic overtures match nicely with the aspirations of many, if not all, the Arctic states. “Asia lagged behind as we developed our global trading routes. Now China, Japan and South Korea are naturally looking at how to make up for lost time, and many of the Arctic governments have ambitions that match China’s long term plans,” Treadwell said.

Only infrequently are the fundamental political differences allowed to surface. As when the Danish Defense Intelligence Service in late 2017 send warning that large Chinese investments into the tiny economy of Greenland and its strategic resources could provide China with an ability to assert “political interference and pressure.” Or as in 2016 when the Danish prime minister, exercising Denmark’s sovereignty over Greenland, intervened to prevent the sale of a derelict former military camp in Greenland to a Chinese mining conglomerate. Greenland is still home to Thule Air Base, an integral part of the missile defense of the U.S., so Denmark must carefully balance its interests. Next challenge may be China’s desire to build a large research station in Greenland. The still sketchy plans would make it the largest research in Greenland, and potentially located — with antennas, drones and all — close to Thule Air Base.

Read China’s new Arctic strategy here.

Martin Breum is a Danish journalist and author specializing in Arctic affairs.

The views expressed here are the writer’s and are not necessarily endorsed by Arctic Today, which welcomes a broad range of viewpoints. To submit a piece for consideration, email commentary (at) arctictoday.com.