Research team injects Inuit views into Ottawa’s plan for safe Arctic shipping

Low-impact shipping corridors informed by local knowledge could go a long way to making shipping in the area safer and less disruptive.

Most Inuit and local informants agree that designated safe shipping corridors planned for Canadian Arctic waters should be set up to protect marine mammals by avoiding sensitive areas wherever possible, while reducing speed and engine noise, a report published late last December says.

They also urge the government to improve safety by doing more charting and getting vessels to avoid certain marine areas that are known to be dangerous.

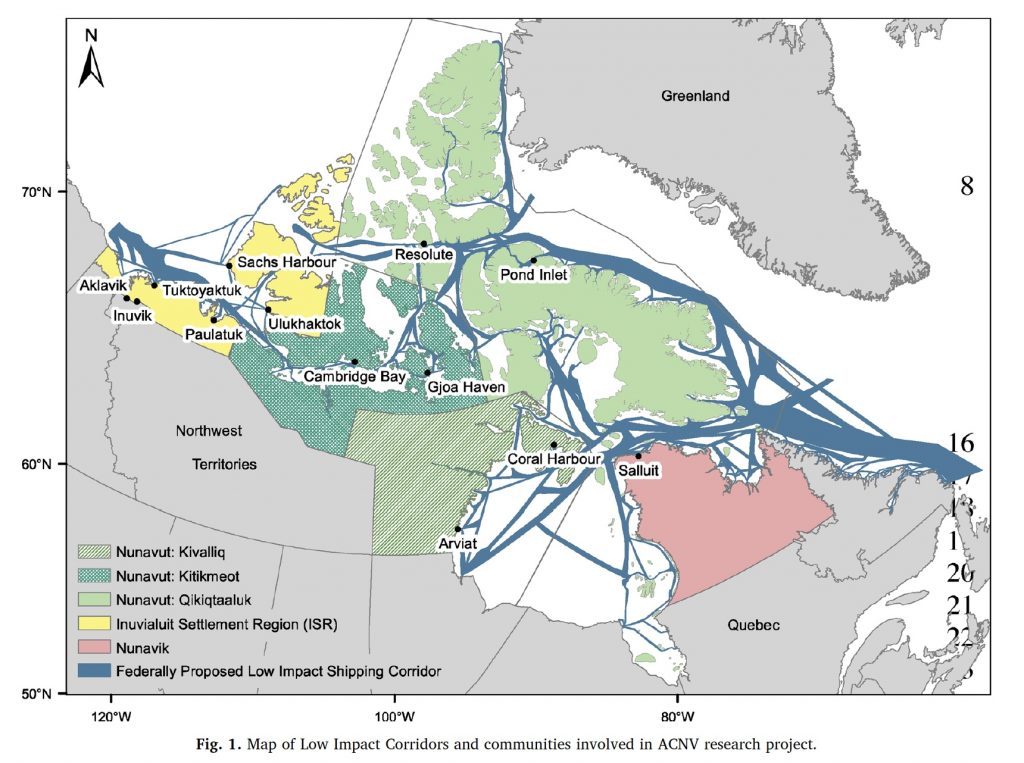

The study, carried out by an eight-person team led by Jackie Dawson, an associate professor at the University of Ottawa’s Department of Geography, summarizes information from people living in 14 coastal communities in the Canadian Arctic.

The report, which includes the views of 126 knowledge holders in 14 communities and reflects the work of 59 community researchers, is part of a project called Arctic Corridors and Northern Voices, also known as “ACNV.”

The ACNV works to ensure Inuit voices are included in a federal government plan to create designated Arctic routes for marine transportation called “low-impact shipping corridors.”

Since shipping volumes in the Canadian Arctic have tripled over the past 10 years, that work is becoming more urgent.

To that end, the federal government has already published maps outlining its preferred routes for Arctic shipping. Those are the corridors that would go to the top of the federal priority list for charting work, infrastructure spending and other activities.

But Ottawa’s work so far hasn’t done much to include the observations of Inuit and other local people.

“The current corridors do not consider the ways in which Arctic communities use the waters located within and around these corridors,” Dawson’s report said.

That’s because, although federal officials used a large amount of information from different sources, they didn’t consider local and traditional knowledge.

So the report by Dawson and her team, published this past Dec. 19, compiles observations and suggestions they’ve gathered so far from Inuit living in the Inuvialuit settlement region, Nunavut and Nunavik.

And they believe that information is essential.

“The findings of the study further reiterate the vital need for meaningful inclusion of northern voices and science alongside federal government agencies in the development of Arctic shipping policy and governance,” Dawson’s report says.

That includes advice on potential dangers to shipping, feeding areas for seals, belugas, narwhal, walrus and bowhead whales, and areas that are culturally important.

For example, people from Resolute and Gjoa Haven recommended that the narrow Bellot Strait be avoided at all times.

The 25-kilometer Bellot Strait is only about 2 kilometers wide and serves as one of the main corridors through the Northwest Passage, but it’s also recognized as hazardous.

“Bellot Strait is well-known by mariners as a difficult area to travel — as dangerous weather conditions and ice can impact safe navigation,” Dawson’s report said.

At the same time, informants from Resolute Bay said that if ships must use Bellot Strait, they should maintain regular contact with the Coast Guard while in the area.

Other suggestions, from the Kivalliq region and Nunavik, urge that vessels avoid an area north of Coats Island, because right now, ships in the area are causing disturbances for marine mammals.

At least four communities — Sachs Harbour, Cambridge Bay, Salluit and Arviat — named specific areas that should be charted, to make corridors safer for ships.

But one area, used frequently for hunting by people from Pond Inlet, is likely to see large amounts of ship traffic anyway.

That’s Eclipse Sound, the main route for mining vessels contracted by Baffinland Iron Mines Corp. that sail in and out of Milne Inlet.

“Pond Inlet community members explained that one of the current corridors is located right in front of the town and directly within the key community hunting area of Eclipse Sound,” the report said.

However, Baffinland’s vessels already have a right of passage through Eclipse Sound, described in the company’s Inuit impact and benefit agreement with the Qikiqtani Inuit Association.

But the report says Pond Inlet community members still suggest that other vessels approach Pond Inlet from the east to minimize travel through the area.

Overall, the report says that people in Arctic communities understand their dependence on marine transportation, but they’re also concerned.

“While communities recognized that shipping can and does provide benefits to their communities — as many of them rely on ships to bring in essential supplies — they more often reflected on the potential negative impacts of shipping,” the report said.

The federal low-impact shipping corridors program, led by Transport Canada, the Canadian Coast Guard and the Canadian Hydrographic Service, started after December 2016, when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Barack Obama, then the United States president, made a joint statement on the Arctic.

In it, Canada and the U.S. promised to establish environmentally sustainable shipping corridors through their Arctic waters.

And once the locations of those corridors are established, the federal government will put those areas at the top of its priority list for charting, navigation infrastructure and other services.

Created in 2014, the ACNV project had already been working with the Coast Guard and people from 14 Inuit communities to gather local knowledge on marine transportation routes prior to that 2106 Trudeau-Obama Arctic announcement.

Their work is funded by Irving Shipbuilding Inc., the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, the Nunavut General Monitoring Program, Oceans North, ArcticNet, the World Wildlife Fund, and many other private and government agencies.