US Arctic research guidelines are getting an overhaul

Federal researchers are updating their research guidelines, and they are asking Arctic communities to weigh in.

For the first time in decades, U.S. federal agencies that conduct research in the Arctic are reexamining the way they do that research.

The Interagency Arctic Research Policy Committee, an organization of 14 federal agencies and offices active in the region, is seeking comment on a draft of new guidelines for conducting research in the Arctic.

The guidelines will replace an outdated version from 1990. The aim is to simplify and update the guidance for researchers, says Renee Crain, program manager at the National Science Foundation’s Office of Polar Programs, who helped oversee the revision.

“In the 1990s document, it talks about ‘informing’ communities if you’re coming to their region to do research,” Crain says. “I think we’ve moved beyond informing to a place where we really want to have dialogue. It’s not adequate to just send an email saying ‘we’re coming.’ What you really need to do is engage in communication.”

Now the committee creating the guidelines wants to hear from as many people as possible about how they might improve them. The official deadline for comments is September 4, 2018. But the committee welcomes feedback even after that date via phone calls and emails.

“It’ll be a better document with more people’s input,” Crain explains. The goal was to make it more useful to researchers and communities alike, with five principles that are “easy to remember and broadly applicable.”

The guidelines first recommend that researchers focus on accountability and two-way communication. “It’s important for researchers to try to engage with people, and communicate in a way that both people have an opportunity to express themselves,” Crain says.

Respect for local culture and knowledge, she says, “doesn’t come as a surprise to anyone, but it’s a good reminder to the research community to remember that there’s a long history of people in the Arctic.” Building and sustaining these relationships with Arctic communities isn’t just polite; it can improve the quality of research.

“We find that it improves the research if you’re able to spend more time and if you’re able to actually build relationships with people,” Crain says. “It’s beneficial to both the research and the people in the Arctic.”

The final tenet, stewardship of the environment, encourages researchers to work on projects that further our understanding of the Arctic environment, while also cautioning them to tread lightly in delicate ecosystems.

“In some cases, there are regulations, and in other cases, it’s really just a matter of paying attention and being mindful of their use of the Arctic and their presence in the Arctic environment,” Crain says.

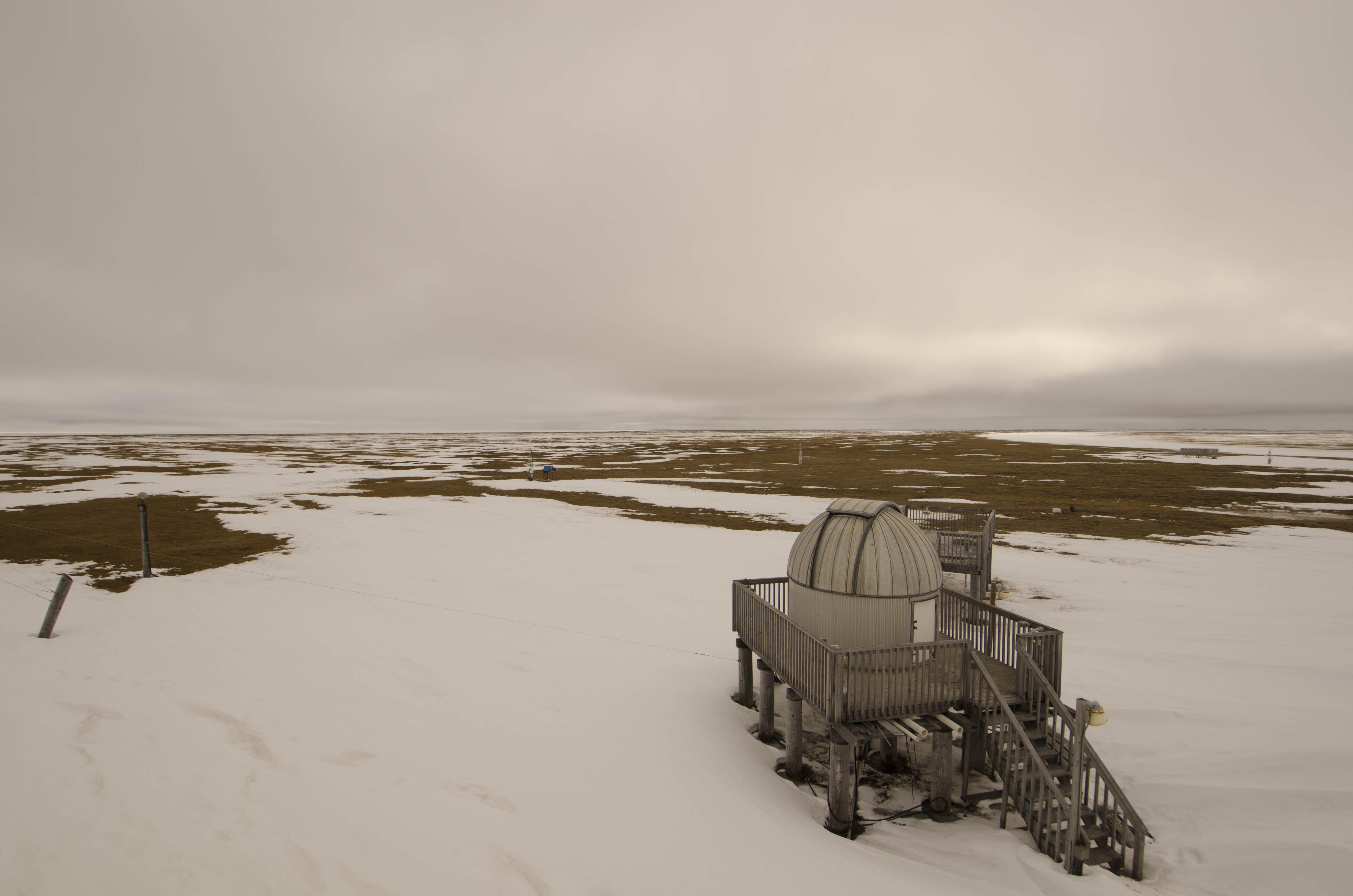

Arctic research methods, both past and present, were a topic of discussion at the recent general assembly of the Inuit Circumpolar Council in Utqiagvik.

“The ethics have not always been good,” said Jim Stotts, president of ICC-Alaska.

Vera Metcalf, an ICC executive board member from Alaska and director of the Eskimo Walrus Commission at Kawerak, urged assembly participants to weigh in on the proposed changes. Metcalf is a former commissioner on the U.S. Arctic Research Commission and also has positions with the North Pacific Research Board and the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy.

Newly elected chair Dalee Sambo Dorough talked about the important role of indigenous knowledge in her closing address to the ICC.

Many countries “have designs for our Arctic homelands,” Dorough said. “Therefore, we must become more assertive about our status and rights to effectively stake what is indeed ours, the land, territories and resources of the Arctic.”

She also quoted from ICC founder Eben Hopson’s welcoming address to the first assembly in 1977. At that time, Alaska’s North Slope oil production boom was just beginning. Hobson was aiming his comments largely at the oil industry, but they are also applicable to researchers working in the Arctic.

“Our language contains the memory of four thousand years of human survival through the conservation and good managing of our Arctic wealth,” Hopson said then. “Our language contains the intricate knowledge of the ice that we have seen no others demonstrate.”

“Without our central involvement, there can be no safe and responsible Arctic resource development.”

The IARPC committee began revising the old guidelines by first asking indigenous communities what should be added and what should be removed. Now the revised document is open for feedback from all who have a stake in Arctic research.

It’s important to open the guidelines to public scrutiny, Crain says, because “there’s a history of making the mistake of assuming what people want — especially for people who are not indigenous to assume things about indigenous communities.”

“If local people don’t find it useful, that’s really important for us to know,” she continues. “We don’t want to be the blundering federal agency.”

“We’ve seen the mistakes,” she adds. “We really want to do the right thing.”

Similar conversations are happening in Canada as well. In March, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, the largest Inuit organization, released a “National Inuit Strategy” intended to guide government and institutions’ research programs and make them a better fit with indigenous people.

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly described Vera Metcalf as a commissioner of the U.S. Arctic Research Commission. She is a former commissioner. This article has been updated to reflect that.