Russia extends its claim to the Arctic Ocean seabed

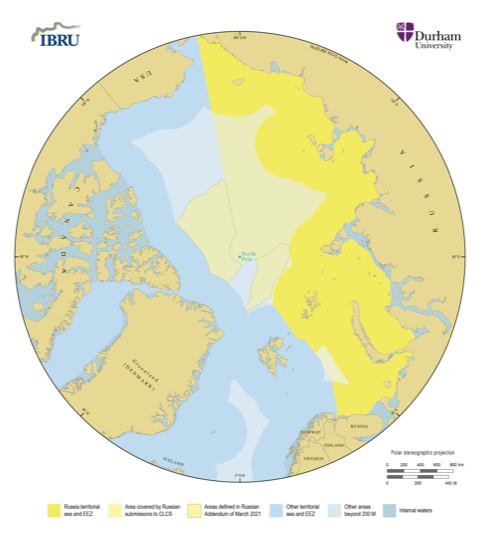

Russia's claim now covers some 70 percent of the seabed in the central parts of the Arctic Ocean and reaches to Canada and Greenland’s exclusive economic zones.

Russia has formally enlarged its claim to the seabed in the Arctic Ocean all the way to Canada’s and Greenland’s exclusive economic zones. The claim is enlarged by two extensions that were filed on Wednesday, stretching from points near the North Pole to Greenland’s and Canada’s exclusive economic zones.

Noticeably, Russia has not extended its claim into waters north of Alaska that are known to be part of the U.S. sphere of interests, even though Russian vessels appear to have collected data about the seabed in these waters in 2020.

Philip Steinberg, professor of political geography and director of the Centre for Border Research at the University of Durham in the U.K., estimated on Saturday that Russia is enlarging its claim by approximately 705,000 square kilometers.

The Russian claim now covers some 70 percent of the seabed in the central parts of the Arctic Ocean outside the EEZs of the Arctic coastal states, Steinberg explained.

2/2: New bits add ca 705k SqKm to Russian seabed, bringing total to 2,103k SqKm. Comparisons: Canada: 1,178k SqKm; Denmark: 907 SqKm. Leaves < 14k SqKm beyond coastal state jurisdiction (using @ibrudurham model of potential US submission). Russian submission = 70% of CAO seabed. https://t.co/2ZSCrS0YRR

— Phil Steinberg (@philbey2) April 3, 2021

The Russian enlargement will significantly increase the overlap between Russia’s claim to the Arctic seabed and the claims filed by Canada and the Kingdom of Denmark.

Those three claims already overlap at the North Pole. The Russian claim now overlaps with the Danish claim with approximately 800,000 square kilometers, up from some 600,000 square kilometers, according to one expert in Denmark, speaking on condition of anonymity because the estimate is unofficial.

Russia filed its enlargement to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf in New York in the form of two so-called addenda. According to the rules of the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea, the enlargement described by the two documents will be dealt with as part of Russia’s existing claim and is not expected to delay the process.

Mission in ice

According to the publicly available summary of the two documents, the enlargement is based on new data collected after 2015. Most recently, between August and October last year, a Russian nuclear icebreaker 50 Let Pobedy broke sea ice between the North Pole and Greenland and Canada, including at points only about 60 nautical miles from Greenland’s EEZ. The ice in this region can still be several years old and several meters thick.

The icebreaker cleared tracks for the Akademik Fedorov, a research vessel with a multibeam echosounder embedded in the hull. This vessel has previously been used by Russia to collect data about the seabed in the Arctic Ocean. The two vessels operated in the characteristic zig-zag pattern also known from Danish-Greenlandic and Canadian data collecting missions in the same waters.

The ships ventured over sections of the Lomonosov Ridge, a subsea mountain range that stretches across the North Pole between Russia, Greenland and Canada, and is a key part of all three claims. The ridge pushes 3,700-meter-tall peaks up from the otherwise flat region of seabed, and the geological nature of the connection between this ridge and the landmasses at either end will help determine which nation has the rights to any potential resources under the seabed.

In November, after the two vessels returned to Russia, the Russian Ministry of Defense published a news release, explaining that the vessels had returned from a three-month mission along the Lomonosov Ridge, as well as the Gakkel Ridge and further west over the Chukchi Plateau north of Alaska.

Closer neighbors

The underlying interests are substantial. A successful claim will bring with it exclusive rights to all resources below the seabed, such as oil and gas, minerals or any other resources — though not resources in the water column, on the ocean surface or in the airspace above. With the rights to the resources on the seabed follow also certain rights to regulate traffic in the area in order to protect those riches on the seabed.

Most experts expect the process to continue peacefully, as the states involved seem determined to follow the rules of the UN. The two Russian documents are written in strict accordance with established procedures and no comments from either Ottawa, Copenhagen or Nuuk have been forthcoming since Wednesday. There is little tradition for quick responses in these proceedings. In 2015, the other Arctic coastal states officially acknowledged a renewed claim by Russia, but only after considerably longer time. A source in Nuuk would only confirm to ArcticToday that Naalakkersuisut, Greenland’s self-rule authority, has been informed about Russia’s enlarged claim (Greenland is party to the process through Denmark).

When I spoke to various experts in January, before the expanded claimed was filed, most suggested that such an expansion didn’t run the risk of inflaming tensions between Russia and other Arctic states, so long as the process continued to play out under UNCLOS rules.

“If Russia enlarges its submission based on new scientific grounds, I cannot see that this needs to have any security implications,” Martin Lidegaard, who is the chairman of the Foreign Policy Committee of the Danish parliament and was Denmark’s minister of foreign affairs when Denmark and Greenland submitted their submission in 2014, said in January. “The Danish Kingdom itself has put forward a large demand, and I assume that we are heading towards difficult negotiations under all circumstances.”

The five Arctic coastal states, Canada, the Danish Kingdom, Norway, Russia and the US have long acknowledged the potential for disagreements over the still undetermined claims to the seabed, and experts and diplomats meet regularly to prevent misunderstandings.

Russia filed its first claim with the CLCS in 2001 and further enlarged its claim in 2015. At this stage, the claim covered the seabed from Russia’s EEZ to the North Pole and a little beyond.

Denmark and Greenland filed their joint claim in 2014, while Canada submitted its claim in 2019. The Danish-Greenlandic claim stretches from Greenland’s EEZ, across the North Pole and to Russia’s EEZ. Canada’s claim covers the North Pole, but does not reach the Russian EEZ.

According to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea the claims, formally known as submissions, can be extended if new data becomes available.

On the basis of the claims, the CLCS will determine to what extent the continental shelf in the Arctic Ocean is a natural prolongation of the bedrock of the states involved.

The CLCS may find that parts of the seabed are firmly connected to more than one state. If this happens, the governments involved will negotiate directly over where exactly to draw the final delineating lines on the seabed.

Flag on the bottom

Russia’s interest in the Arctic seabed has long been evident. In 2007, two small Russian submarines dove 4,300 meters to the bottom of the Arctic Ocean at the North Pole, planting a Russian flag.

Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov called for calm: The U.S. flag on the moon did not lead to any U.S. claims of ownership either, he said, and Russia has since adhered scrupulously to the rules of the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea.

More recently, Russia aired its confidence that the CLCS will eventually determine in Russia’s favour.

In 2019, the Russian Ministry of Natural Resources issued a statement indicating that the 50th session of the CLCS in August 2019 had resulted in the approval of key points in Russia’s submission. According to the Barents Observer, the Ministry said that the CLCS had agreed that the Lomonosov Ridge, the Mendeleev Ridge, as well as the Provodnikov Basin are underwater plateaus and natural extensions of the Russian shelf.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story incorrectly reported that Martin Lidegaard was the former chairman of the Foreign Policy Committee of the Danish parliament at the time of publication. The story has been updated to reflect that he holds that position currently.