Russian gas pipelines to go ahead despite U.S. sanctions

MOSCOW/BRUSSELS — New U.S. sanctions will make it harder for Russia to build two gas export pipelines to Europe but the projects are unlikely to be stopped.

U.S. President Donald Trump has reluctantly signed further sanctions on Russia into law, but some of the measures are discretionary and most White House watchers believe he will not take action against Russia’s energy infrastructure.

This would allow Gazprom’s two big pipeline projects to go ahead — although at a higher price and with some delays.

[Another big win for Russian pipeline politics in Europe?]

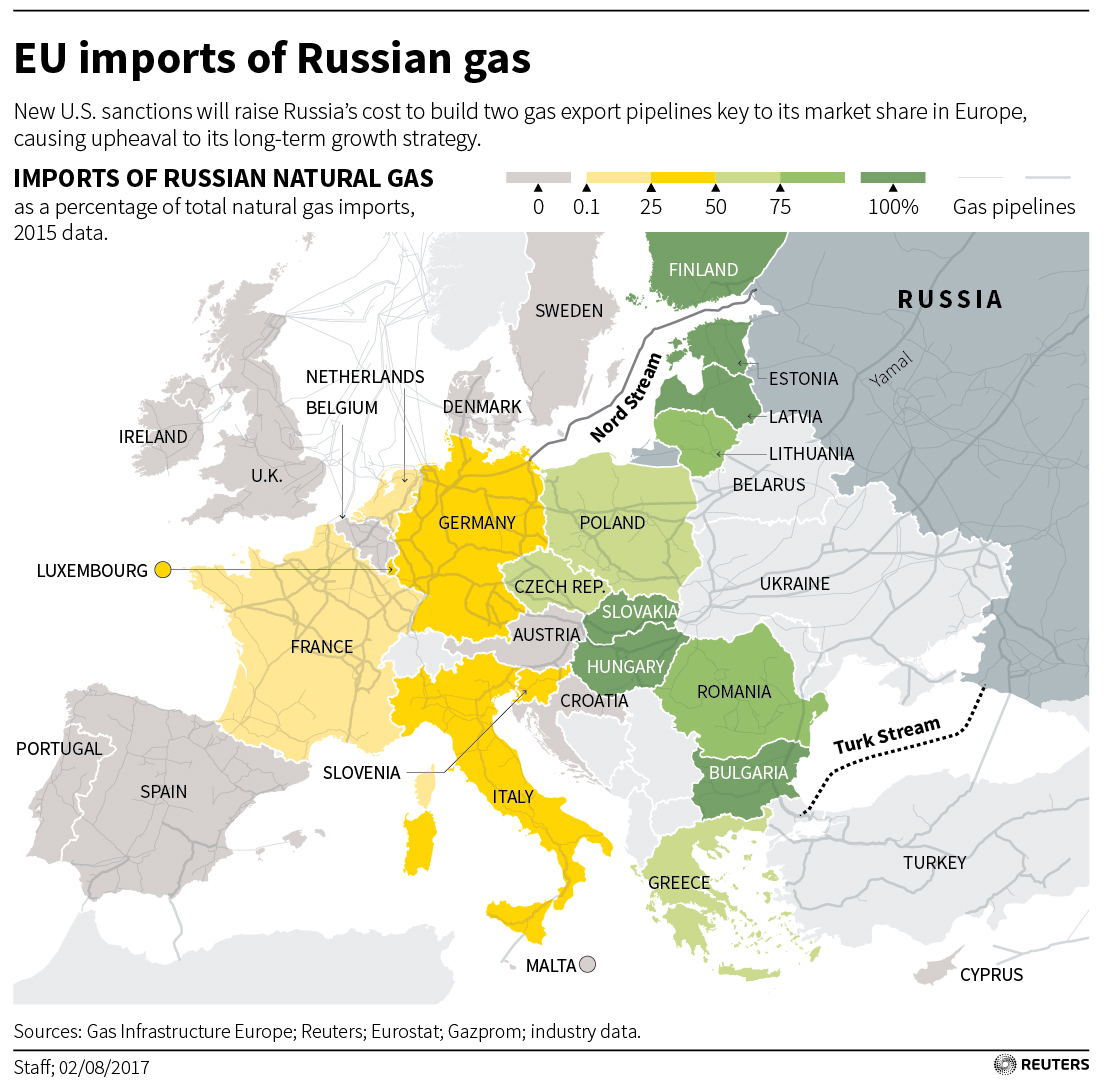

The Kremlin, dependent on oil and gas revenues, sees the pipelines to Germany and Turkey — Nord Stream 2 and TurkStream — as crucial to increasing Russia’s market share in Europe.

It also fears that Western partners – needed to develop the deepwater, shale and Arctic gas deposits that will fill the pipelines – will be scared off by sanctions.

Gazprom warned investors last month that the sanctions “may result in delays, or otherwise impair or prevent the completion of the projects by the group.”

With all that in mind, the Russian gas giant is taking steps to reduce the sanctions’ impact.

It has accelerated pipe-laying by Swiss contractor Allseas Group under the Black Sea for TurkStream – even though there is no final agreement on where the pipeline will make landfall in Turkey. It is also hurriedly building a second TurkStream line to export gas to Europe.

“The construction of the second line is underway just in case the sanctions hit,” a senior Gazprom source told Reuters.

A spokesman for Allseas said 100 kilometers (about 60 miles) of the 900-kilometer (bout 560-mile) first line have been built since June 23 and preparatory work is underway for the second line.

THE UKRAINIAN CONNECTION

The biggest cost of any delays to the new lines could come from increased transit fees paid to Ukraine, the route by which Russian gas has traditionally reached Europe.

Nord Stream 2 and TurkStream bypass Ukraine, but if they are brought into use late, Gazprom will have to continue using the Ukrainian route and may have to pay more for the privilege.

The European Union, fearing sanctions will hurt oil and gas projects on which it depends, said it was ready to retaliate unless it obtained U.S. guarantees that European firms would not be targeted.

Five Western firms that have invested in Nord Stream 2 – Wintershall and Uniper of Germany, Austria’s OMV, Anglo-Dutch Shell, and France’s Engie – say it is too early to judge the impact of sanctions.

For now, they are standing by their pledge of up to 950 million euros ($1.13 billion) each to finance the 1,225-kilometer (760-mile) Nord Stream 2.

Despite Trump’s desire to promote U.S. liquefied natural gas exports to Europe that would compete with the Russian gas, he said he did not want the sanctions to get in the way of efforts to resolve the conflict in Ukraine.

EU officials, industry sources and experts therefore doubt that Trump will use what he regards as “significantly flawed” sanctions to punish Moscow.

“Their approach is going to be strictly by the letter of the law: what do they have to do,” Richard Nephew, a former U.S. deputy chief of sanctions now with Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

RISK PREMIUM

The sanctions law is however expected to hamper Gazprom’s efforts to raise money.

“The price of any project automatically increases,” said Tatiana Mitrova, director of the Skolkovo Energy Center.

“Gazprom’s relationships with partners, subcontractors, and equipment and service providers are severely complicated,” she said. “They will all ask for a risk premium.”

Gazprom will have to take on the additional cost itself, depend on Russian state banks, or seek money at higher rates from Asian lenders, financial analysts said.

“This, however, does not mean that Nord Stream 2 won’t be built,” said Katja Yafimova of the Oxford Energy Institute.

[EU stalls Russian gas pipeline, but probably won’t stop it]

Industry sources say the loans from Western partners for Nord Stream 2 are already at above market rates to reflect the political risk of partnering with Russia in a project that has also faced opposition in Europe.

The added uncertainty ups the stakes further. “It’s like reading tea leaves,” one source with knowledge of the European side of the Nord Stream 2 financing structure told Reuters.

While big players may be able to stomach the risk, analysts say the smaller contractors on which Gazprom depends to build the pipelines may get spooked. “Not all partners can afford to see things through with Gazprom,” said Valery Nesterov, an analyst at Moscow-based Sberbank CIB.

A spokesman for Nord Stream 2 said more than 200 non-Russian companies from 17 countries, most of them European, are building the pipeline. Most of the big contracts for steel, port logistics and construction have already been concluded.

By forcing the pace of construction, Gazprom may have gained enough time to build the new pipelines but longer-term projects will take a hit.

“Unless Trump takes a really sharp turn, it is highly unlikely that companies that are supplying pipeline goods are going to be punished in the next year or so,” Nephew said. “A lot of companies are now thinking: ‘I’ve got maybe 12, maybe 18 months in which I can do some stuff but after that maybe I won’t’.”

Additional reporting by Vladimir Soldatkin in Moscow, Shadia Nasralla in Vienna, Vera Eckert in Frankfurt, Ron Bousso and Nina Chestney in London.