Russia’s extension of US overflight rights hurts the Arctic

ANALYSIS: A deal to allow overflights of Russian airspace by American passenger planes is good for international relations — but bad for the Arctic environment.

Every week, hundreds of flights on U.S. airlines pass through Russian airspace. Only a handful of these flights actually start or end in Russia. Most are between the U.S. and Asia or the Middle East, for which the fastest routes necessitate flying over the Arctic and across Russia’s vast Siberian tundra. The Russian Arctic and the Russian Far East might be far from most people’s minds, but for trans-Pacific travelers, these regions form a shortcut that makes long-haul travel just a little bit more bearable. For the Arctic, however, cross-polar flights bring black carbon and harmful emissions and very few tangible benefits.

Permission to fly over a country’s territory generally requires permission from the national government. That permission generally needs to be re-approved every few months, something that can’t always be counted on if relations between two countries are in a downward spiral. Russian’s overflight approvals for U.S. airlines were due to expire on April 17. With relations between the U.S. and Russia having imploded over the past few months, a situation that the U.S. missile strikes in Syria over the weekend exacerbated, the re-approval outlook was not looking good. First, Russian civil aviation officials had pulled out of a scheduled meeting in Washington, D.C. to discuss overflight agreements. Second, on Saturday, April 14, American Airlines’ three flights that overfly Russia – Dallas-Beijing, Dallas-Hong Kong, and Chicago-Beijing – were rerouted to avoid Russian airspace. It’s not clear whether American Airlines had actively decided to avoid Russian airspace following the heightening of tensions between the U.S. and Russia in Syria or whether Russia had temporarily rescinded that airline’s permission to fly over. In any case, all three flights had to stop on the West Coast to refuel before taking the second legs of their journeys directly across the Pacific Ocean to their destinations. In some cases, the extra stop added up to eight hours of travel time.

[U.S. airline group says deal reached to fly in Russian airspace]

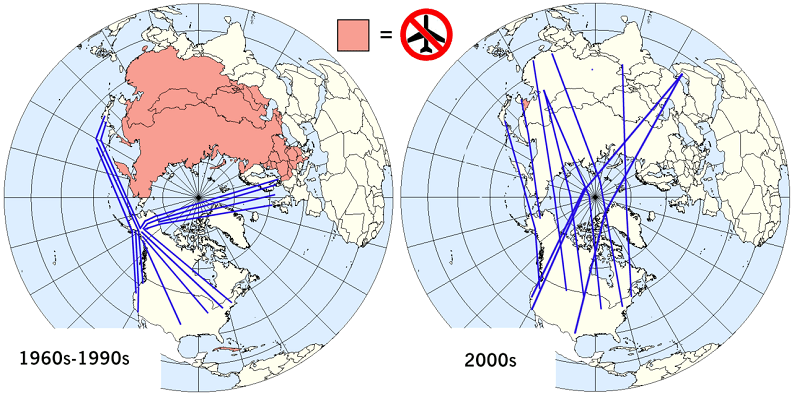

In light of the possibility for souring geopolitics to severely curtail American aviation, government officials, airline representatives, and frequent flyers were left waiting in suspense to see if travel between the U.S. and Asia would be rocketed out of the 21st century Russian Arctic and back to the 20th century Cold War. Until the early 1990s, U.S. airlines had to stop in Anchorage to refuel before flying around the borders of the Soviet Union en route to places like Japan rather than flying more directly over Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula. This series of maps from Wikipedia shows how air traffic has been redirected to more efficient routes thanks to geopolitical rather than technological improvements.

In the end, the looming crisis was avoided. Russia came around and decided to extend the overflight rights of U.S. airlines by another six months. Heather Nauert, a spokesperson for the U.S. State Department, expressed, “The Russian government did say to our embassy, when we spoke with them: ‘Don’t panic, we’re not going to do anything to harm the U.S. aviation sector.’” These days, it seems it’s the Kremlin that is more level-headed than the Oval Office.

The environmental toll of cross-polar aviation

As the Cold War came to a close, the emergence of favorable relations between Russia and the West opened the door to faster routes. These end up being better for the planet’s overall environment since they require less fuel and generate fewer carbon emissions. Specifically for the Arctic, however, the expansion of cross-polar aviation has increased the amount of emissions released in the region, which take a more severe toll than they would elsewhere. The Arctic has less precipitation then more southern latitudes, meaning that there are fewer occasions for the weather to literally help clear the air. One studyby researchers at Stanford found that aircraft vapor trails were responsible for 15-20% of warming in certain parts of the Arctic. Their follow-up work, published in the journal Climactic Change, concluded that while rerouting planes to avoid the area north of the Arctic Circle would increase global fuel usage by 0.056% on average, it would reduce fuel use and emissions north of the Arctic Circle by 83%. Their model suggests that rerouting planes could cost $99 million a year in additional fuel, but that the value to the U.S. alone in terms of slowing climate change and reducing the melting of the Arctic ice cap could be up to 55 times greater than that seemingly hefty price tag.

While passengers and airline CEOs can breathe a sigh of relief that their travel times and bottom lines will not be disrupted by a need to reroute around Russia, the Arctic – specifically Alaska and the Canadian and Russian Arctic, the areas that airplanes fly over between the U.S. and Asia – will continue to bear the brunt of these rapid connections. The story is much the same with polar shipping: as more maritime vessels seek shorter routes between Asia, Europe, and North America via the Arctic, more pollution will end up in the Arctic’s waterways, with Arctic communities receiving little of the benefit of their home becoming a global shortcut. Pollution from vessels that go by like ships and planes in the night may be invisible to travelers sitting in their seats 30,000 feet above Siberia, glued to the in-flight entertainment system and loading up on pretzels. But contrails and their consequences are highly visible to the Arctic’s residents down below, who reap none of the rewards of these overhead flights (save for some trickle-down economics from overflight fees).

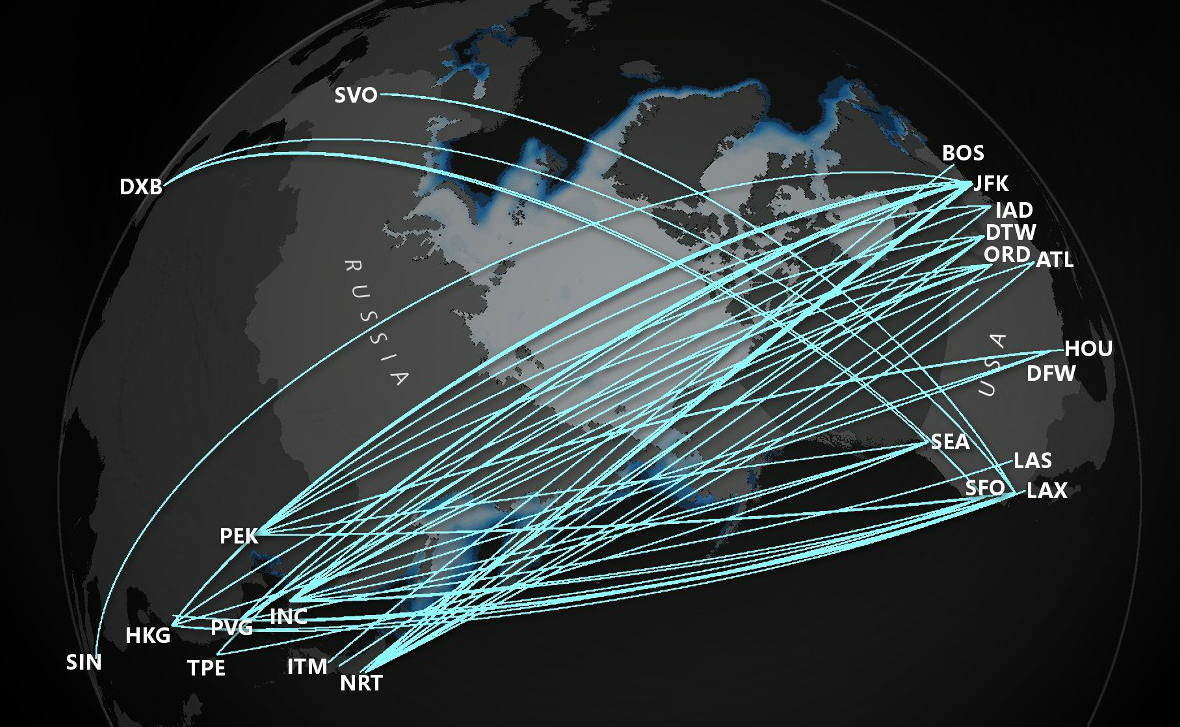

I tried to visualize the impact of pollution from cross-polar aviation in the infographic below. While most aviation maps, like the second figure below, emphasize connectivity, by removing the lines connecting airports together and instead only showing their shadows – a symbol for their contrails and emissions – the resulting image better conveys the environmental consequences of humanity’s race to connect ever more places.

30,000 feet over Yakutsk

As it turns out, I was one of those passengers scheduled to fly from Dallas to Hong Kong on American Airlines this past weekend. Fortunately, my flight was booked for Sunday rather than Saturday. After American Airlines rerouted its flights from Texas to Asia through Los Angeles on Saturday, things were surprisingly already back to normal on Sunday. I therefore had the opportunity to fly over Siberia. For the 17-hour flight, despite wanting to take in the view as much as possible, I chose an aisle rather than a window seat so that my legs would not completely turn into jello by the time I got to Hong Kong. As the pixellated plane inched forward on the digital flight map, finally, I saw, we were going to zoom right over Yakutsk – the city where I’d done research two years before. I walked to the back of the plane and opened a window in the galley. The blinding whiteness of the monochrome vista swiftly poured into the back of the airplane. Though it was a gray and foggy day, sunlight bounced off the snow and ice in every direction. Below the plane was the enormous, and still deeply frozen, Lena River. A few straight black lines etched across it were the telltale signs of ice roads. The city of Yakutsk spread out on its western bank, gray rectangles whose geometry contrasted with the curvilinear river. Frozen lakes pockmarked the permafrost-laden landscape. All seemed peaceful below, but the Boeing 777 encapsulating us was spewing at least 50 pounds of carbon dioxide for every mile traveled.

A view from the ground

As I went back to my aisle seat, I remembered how a few summers ago on a hot and buggy day, I was sitting in a boat in northwest Canada’s Mackenzie Delta. A plane flew overhead, scraping a straight white line into the blue sky. Floating on the water, I imagined a couple hundred people bunched together with not quite enough legroom. Some passengers were probably trying to pass out on the free alcohol, while others were strategizing how they would defeat jet lag. Maybe they would try to stay up for the entire flight drinking copious amounts of coffee and binge-watching whatever series was available. At the time, I’d wondered where the plane was headed. Now, I have a better idea. It was likely bound for somewhere over Russia, and then, probably Asia.

It’s pretty weird to think that only vertical miles were separating these two vastly different spaces: a jumbo jet and a little boat on an Arctic river. They’re only brought together in dramatic fashion in times of emergencies and unscheduled landings, as I’ve written about before. High above my little boat in the Mackenzie River were people raking in frequent flyer miles and free food and drink (however much they’d complain about the quality), watching movies and maybe even using the satellite wifi, while on their way to an Asian megalopolis. On the ground were people in the Arctic whose mobility tends to be severely limited by the high cost of plane flights, where milk costs an arm and a leg, and where internet access can’t always be relied upon. All in all, I consider myself extremely fortunate to have experienced life both in and above the Arctic. With that comes the realization that the privileges and efficiencies of the space above come at the cost of those below.

Mia Bennet is assistant professor of geography at Hong Kong University’s School of Modern Languages and Cultures, and writes at Cryopolitics, where this piece first appeared. It is republished here with permission.

The views expressed here are the writer’s and are not necessarily endorsed by ArcticToday, which welcomes a broad range of viewpoints. To submit a piece for consideration, email commentary (at) arctictoday.com.