Scientists amazed as Canadian permafrost thaws 70 years early

Latest evidence of global warming suggests the temperatures are warmer than at any time in the past 5,000 years.

LONDON (Reuters) — Permafrost at outposts in the Canadian Arctic is thawing 70 years earlier than predicted, an expedition has discovered, in the latest sign that the global climate crisis is accelerating even faster than scientists had feared.

A team from the University of Alaska Fairbanks said they were astounded by how quickly a succession of unusually hot summers had destabilized the upper layers of giant subterranean ice blocks that had been frozen solid for millennia.

“What we saw was amazing,” Vladimir E. Romanovsky, a professor of geophysics at the university, told Reuters by telephone. “It’s an indication that the climate is now warmer than at any time in the last 5,000 or more years.”

With governments meeting in Bonn this week to try to ratchet up ambitions in United Nations climate negotiations, the team’s findings, published on June 10 in Geophysical Research Letters, offered a further sign of a growing climate emergency.

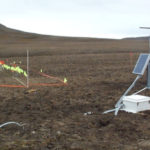

The paper was based on data Romanovsky and his colleagues had been analyzing since their last expedition to the area in 2016. The team used a modified propeller plane to visit exceptionally remote sites, including an abandoned Cold War-era radar base more than 185 miles (300 km) from the nearest human settlement.

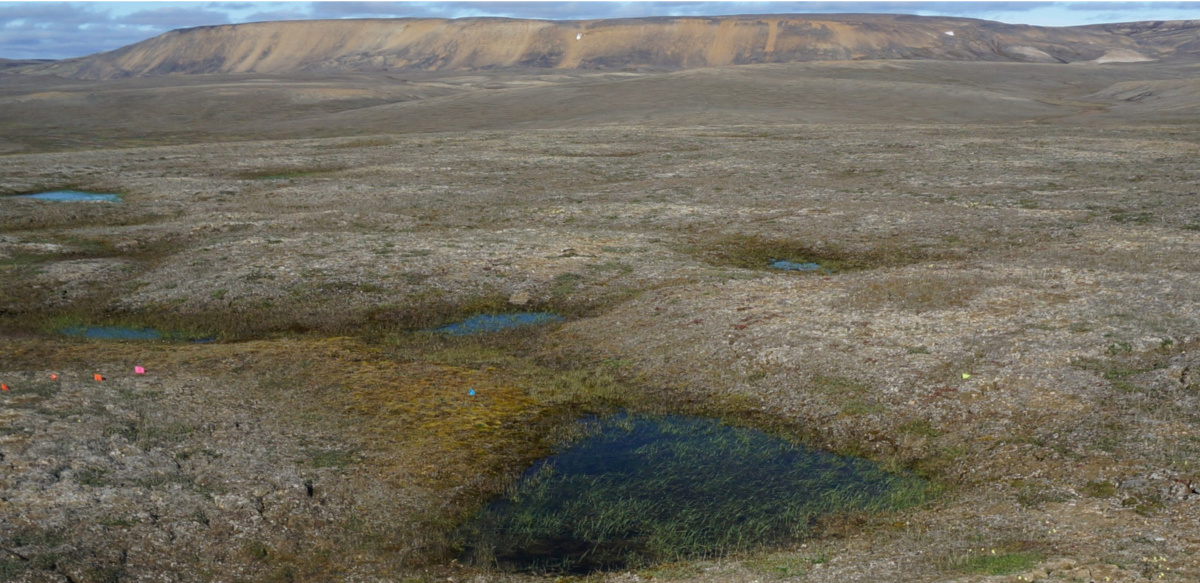

Diving through a lucky break in the clouds, Romanovsky and his colleagues said they were confronted with a landscape that was unrecognizable from the pristine Arctic terrain they had encountered during initial visits a decade or so earlier.

The vista had dissolved into an undulating sea of hummocks — waist-high depressions and ponds known as thermokarst. Vegetation, once sparse, had begun to flourish in the shelter provided from the constant wind.

Torn between professional excitement and foreboding, Romanovsky said the scene had reminded him of the aftermath of a bombardment.

“It’s a canary in the coalmine,” said Louise Farquharson, a post-doctoral researcher and co-author of the study. “It’s very likely that this phenomenon is affecting a much more extensive region and that’s what we’re going to look at next.”

Scientists are concerned about the stability of permafrost because of the risk that rapid thawing could release vast quantities of heat-trapping gases, unleashing a feedback loop that would in turn fuel even faster temperature rises.

Even if current commitments to cut emissions under the 2015 Paris Agreement are implemented, the world is still far from averting the risk that these kinds of feedback loops will trigger runaway warming, according to models used by the U.N.-backed Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

With scientists warning that sharply higher temperatures would devastate the global south and threaten the viability of industrial civilization in the northern hemisphere, campaigners said the new paper reinforced the imperative to cut emissions.

“Thawing permafrost is one of the tipping points for climate breakdown and it’s happening before our very eyes,” said Jennifer Morgan, executive director of Greenpeace International. “This premature thawing is another clear signal that we must decarbonize our economies, and immediately.”

(Reporting by Matthew Green; Editing by Mark Heinrich)