Scientists inside and out of the federal government raise concerns about Arctic refuge drilling

The researchers point to inadequate information about how natural resource exploration would affect the environment, wildlife and Indigenous communities.

Documents released last week by Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility reveal concerns from U.S. government scientists about drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

PEER released memos from scientists in federal agencies, including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, identifying research gaps early last year in preparation for the ANWR scientific review process, which they noted was planned to take five years.

PEER says that these memos were hidden by the Interior Department and that freedom of information requests to access the documents were denied, according to an article from E&E News, which first reported on the memos.

The federal researchers called for detailed analyses prior to seismic testing, infrastructure planning and natural resource exploitation in the 1002 area. In particular, they noted the need for extensive research on potentially disrupting polar bear habitats and caribou ranges in the region, as well as the effects of exploration on water quality and availability, subsistence hunting, and public health, among other topics.

In all, these assessments would cost approximately $5 million to conduct, the scientists estimated.

To reach these conclusions, USFWS scientists consulted with experts in the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Geological Service, Bureau of Ocean Energy and Management and National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, as well as several Alaska state agencies, the North Slope Borough, the oil and gas industry and federal and territorial agencies in Canada.

Separately, 312 scientists signed an open letter to BLM outlining their own concerns with the draft EIS earlier this month.

“I did biological surveys in what is now the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in 1952 and 1956 and again in 2006 and 2008,” said George Schaller, of the Wildlife Conservation Society, in a statement. “Having read the BLM draft environmental impact statement, I’m distressed and disconcerted by the lamentable lack of solid information” about the effects of oil development, he said.

The letter pointed to a lack of adequate data in the draft EIS, including information on snow, water and wildlife populations — not just polar bears and caribou but also fish, birds, grizzly bears, wolves, wolverines and muskoxen.

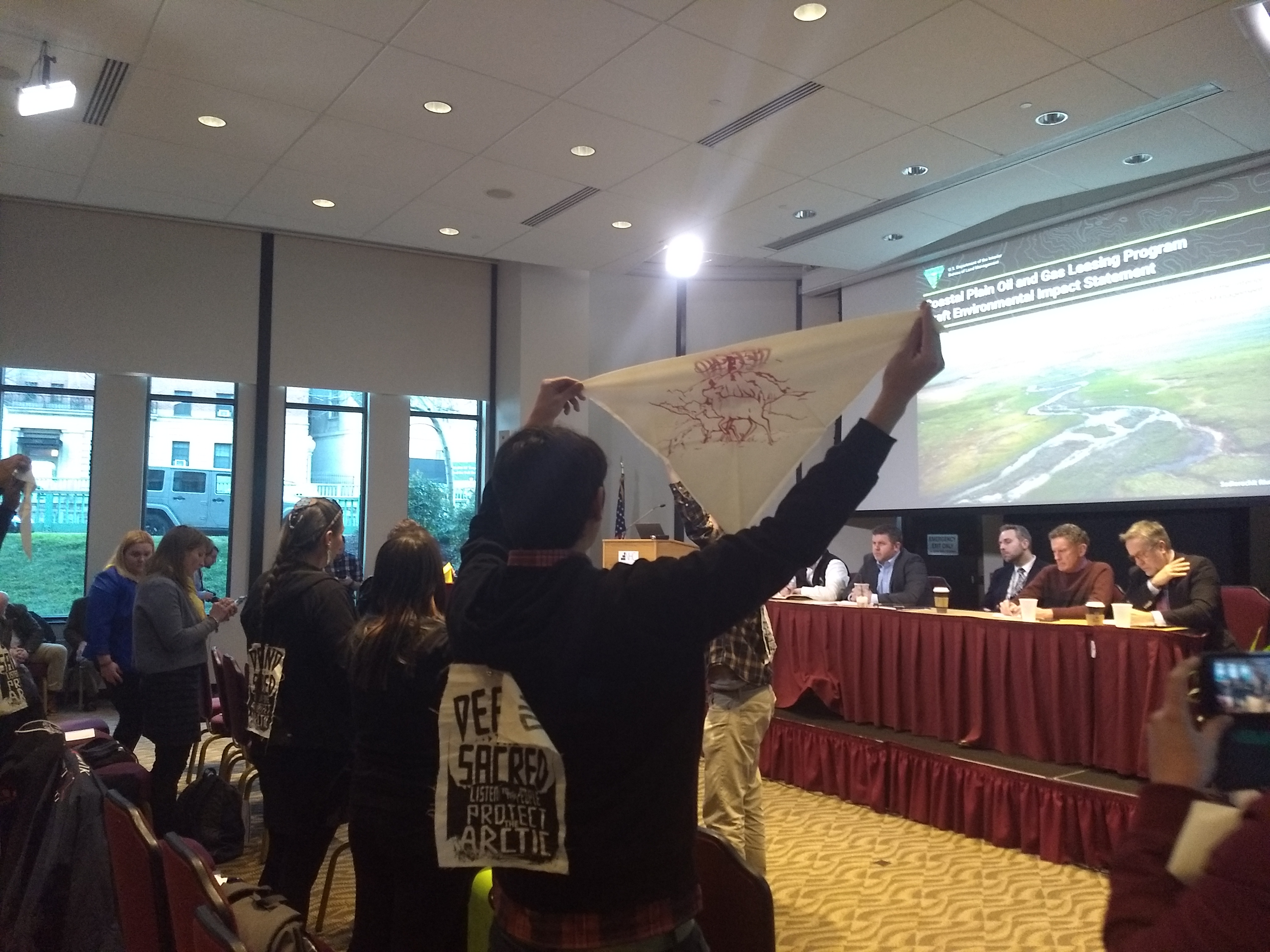

After releasing a draft environmental impact statement late last year, the Bureau of Land Management conducted eight public meetings in ten days, in Fairbanks, Kaktovik, Utqiagvik, Fort Yukon, Arctic Village, Venetie, Anchorage and DC. The official public comment period extended from December 28 to March 13.

Critics contended that the hearings were rushed, without proper consultation with affected communities. The only hearing conducted outside of Alaska took place in Washington, D.C., on February 13.

At the Washington, D.C. hearing, Adam Kolton, the executive director of Alaska Wilderness League, said that the provision to open ANWR up to oil and gas exploration was “jammed in the tax bill without a full fair and open debate” and without a vote in the House of Representatives.

“There was no fair process,” he said. The Trump administration had testified before Congress that there would be a four- to five-year process to examine the effects on the region before conducting a lease sale, he said.

“Well, you’re trying to do it in two years. That’s not what you testified to, and the tax bill actually gave you twice the time,” Kolton said.

Alaska Sen. Lisa Murkowski, a Republican and author of the tax bill’s ANWR drilling provision, told an Anchorage business group last February that the process was moving forward quickly “because once you get those leases out into the hands of those who can then move forward, it’s tougher to throw the roadblocks in place.”

Kolton pointed out, however, that the tax bill requires a similar process in ANWR as the National Petroleum Reserve Act.

“You’re doing nothing like that,” he said. “You’re not following the law.”

But officials say that they are abiding by the tax bill’s provisions.

“Right now, we’re following the law, as Congress has made it. If Congress seeks to change it, we’ll follow the law in the future,” Joe Balash, assistant secretary for land and minerals management in the U.S. Department of the Interior, told ArcticToday in February, at the time of the Washington hearing.

“The only thing that would prevent us from following the law and holding a lease sale within the four years required, would be for Congress to change its mind, whether that be through a change in substantive law or some other means,” he added.

Representatives in the House recently introduced a bill to amend the tax law by removing the ANWR drilling provision, but observers note that the Senate and White House are still controlled by Republicans who support natural resource exploration.

Yet Kolton argued that following the law, and fulfilling the promises made during the tax bill debate, would involve a longer and more detailed review of effects on the land and those who depend upon it.

“We suggest that you scrap the EIS, start over, do a better job,” he said to applause from others at the hearing.

Several speakers also highlighted the lack of attention paid in the EIS to the effects upon indigenous communities in and around the 1002 area.

Donna Tritt, who is Gwich’in from Arctic Village, noted that “there is no direct impact to the native people in the EIS, and that’s completely false.”

Rhonda Anderson, who is Inupiaq Athabaskan originally from Kaktovik, pointed out that the meeting times and places, as well as the languages in which the meetings are conducted, should have been determined by the Indigenous communities.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2007, specific mentions obtaining free, prior, and informed consent from Native communities before conducting any activities that might affect their ancestral lands and livelihoods, she pointed out.

“I have quite a few family members on the North Slope in Kaktovik that had no idea that there was a meeting on Monday in Anchorage,” Anderson said.

Several speakers at the D.C. hearing also testified to the difficulty of cleaning up oil spills and other effects of drilling in a remote and harsh environment.

Chuck Feerick, from Fairfax, Virginia, was an environmental analyst for the oil and gas industry for more than 40 years.

“There is no technology, there is no methodology, there is no approach, there is no way that you can go into a pristine environment like the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and not cause irreparable damage and extensive desecration of the area,” Feerick said. “It cannot be done.”

“The world is awash in cheap oil and gas,” he said. “We really don’t need more oil production; what we need are more national wildlife refuges.”