Seismic surveys on the coastal plain of Alaska’s Arctic refuge would cause long-lasting damage, study says

The study builds on earlier work that found the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge's terrain far less conducive to seismic exploration than other parts of Arctic Alaska.

When a team of Alaska scientists warned more than a year ago that seismic surveys for oil in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge coastal plain would have dire environmental consequences, a top Department of the Interior official shrugged off the findings.

“It appears to be, on its face, anyway, something that has a specific purpose and agenda. That’s not really the way science is conducted. Normally you start out with a hypothesis, gather your data, test it against your hypothesis and report your results,” Joe Balash, then the Department of the Interior’s assistant secretary for minerals and management, said shortly after the team’s white paper came out.

Now that work by the Alaska scientists, who are Arctic specialists mostly affiliated with the University of Alaska Fairbanks, has been checked and validated by scientific peers. The findings of the white paper, released near the end of 2018, are detailed in a study published in the journal Ecological Applications.

“Really, the main difference is peer review and the quality control. So the words are bearing more weight in the report,” said co-author Anna Liljedahl of the Woods Hole Research Center and UAF.

Momentum for oil exploration in the refuge, meanwhile, has slowed. Though Balash last year vowed that a lease sale would be held before the end of 2019, no sale has yet been scheduled. Though geologic exploration company SAExploration applied in 2018 for approval to send “thumper” vehicles across the coastal plain to conduct seismic surveys for oil potential, that application has languished.

The hiatus allowed scientific research to catch up a bit to the oil development process, said Martha Raynolds of UAF’s Institute of Arctic Biology, the first author of the newly published peer-reviewed paper.

“Academia sort of crawls along at this pace and sometimes industry leaps,” Raynolds said.

As the scientists’ white paper did, the newly published peer-reviewed study warns that the type of vehicle travel and industrial activity routinely used for exploration and development on flat expanses of the North Slope cannot safely be used on the hilly, varied and distinct terrain of the Arctic refuge coastline.

While oil companies use snow and hard-frozen ground to support their travels around Prudhoe Bay, other established oil fields and the frontier areas on the western North Slope, the refuge coastal plain on the eastern North Slope is different in important ways, the scientists point out.

That starts with the slope, Liljedahl said. “Really, that gradient is just a whole other game when it comes to hydrology,” she said. “It can increase the disturbance ten-fold.”

Snow, vegetation, permafrost, wildlife populations and other characteristics also add to the vulnerability, putting the refuge’s coastal plain at extra risk of impacts from vehicles traversing the tundra to conduct seismic surveys and other industrial activities, the newly published paper says.

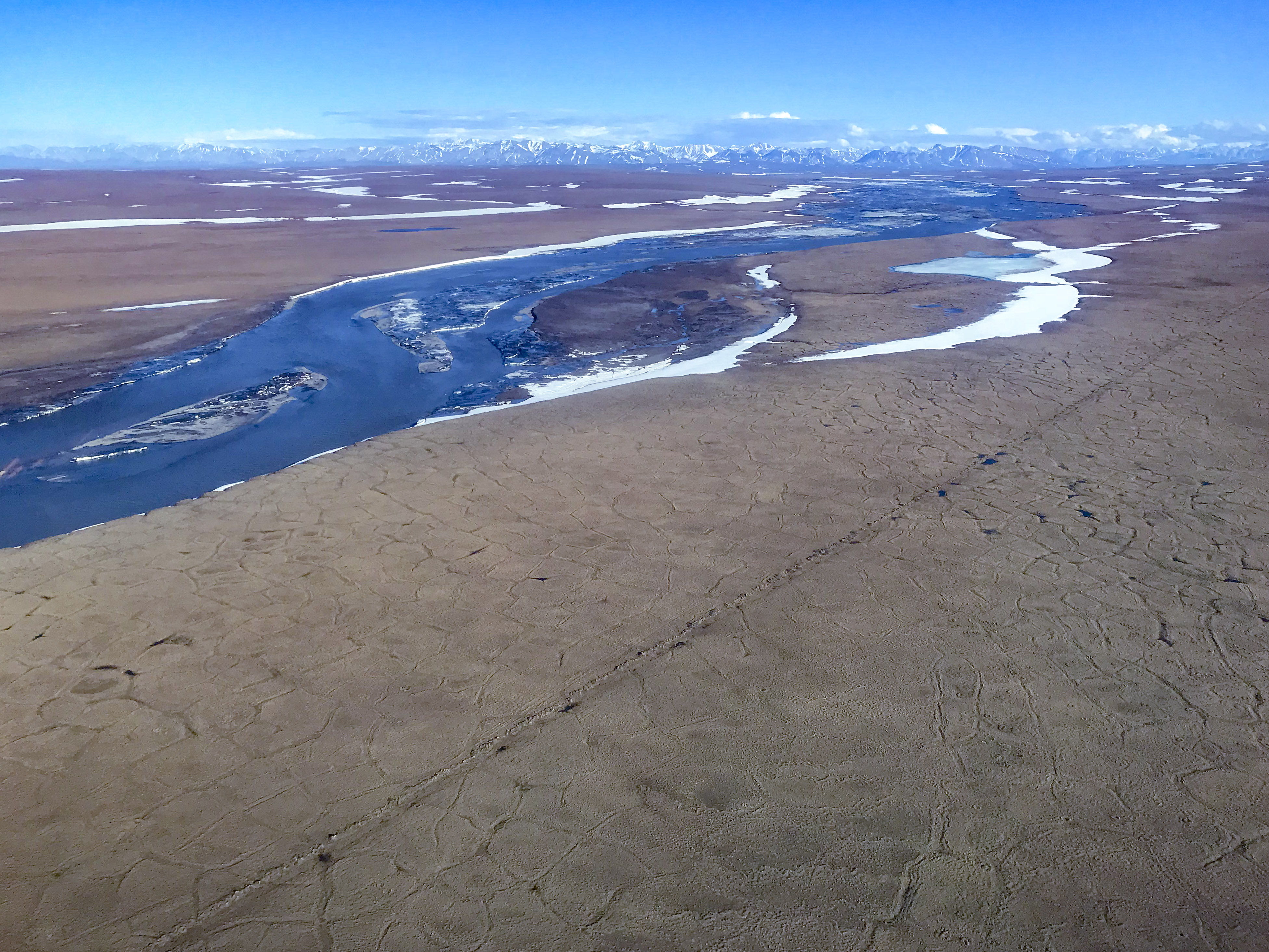

The refuge coastal plain is a relatively narrow area wedged between the ocean and the Brooks Range mountains, a contrast with the Prudhoe Bay area.

The proximity of mountain peaks, looming within sight of the coastline, funnels winds that scour parts of the tundra, removing snow from some areas and depositing it in others. Those high winds remove snow that, elsewhere on the North Slope, is used as a buffer to protect the delicate tundra from the weight of industrial vehicles, the study said.

The coastal plain also lacks the freshwater or gravel sources that are abundant farther west on the North Slope. Water from lakes is needed to build temporary ice roads and pads that the industry uses for winter travel, and gravel is used for permanent roads, pads and airstrips.

When it comes to gravel, Prudhoe Bay’s location is serendipitous, Raynolds said. Alaska’s biggest oil field is blessed with plentiful gravel located relatively near the ground surface — the product of ancient erosion into rivers from an earlier, bigger version of today’s Brooks Range, she said.

“At Prudhoe Bay, when they want to build a pad, there’s gravel everywhere,” she said.

In contrast, gravel in the refuge coastal plain would have to be mined from bedrock, she said.

To help understand the potential impacts of future seismic surveys in the refuge coastal plain, the scientists evaluated the environmental legacy of past seismic surveys on the North Slope. Those include the 2-D surveys that were done on Native-owned land within the refuge coastal plain prior to the drilling of a single exploration well in 1986.

In some of those sites, including the areas explored in the 1980s, survey lines compressed the ground and the delicate, slow-growing plants on it, becoming scars on the tundra that took years and sometimes decades to heal, the paper notes.

The 3-D surveys that SAExploration proposed to do had the potential to cause even worse harm that past surveys, the study authors said. The company’s plans were for a much tighter grid of survey lines made by bigger vehicles and served by bigger crew camps, they noted.

Additionally, permafrost is much warmer than it was in the 1980s, when the old 2-D surveys were conducted, the paper noted.

Warming permafrost is a concern beyond the Arctic refuge coastal plain, Liljedahl said. “For any level of disturbance that is done, we’re just really closer to the threshold,” she said. “I totally think there ought to be a review of what’s always been done.”

Since last year, when oil exploration appeared imminent on the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge coastal plain, much has changed.

Prices for oil that were already low because of a glut on world markets fell further as the coronavirus pandemic spread. Opportunities for financing Arctic refuge oil development or any new Arctic oil development have dwindled as numerous financial institutions announced policies forbidding lending for such projects. In Alaska, companies have reduced operations drastically, abruptly ending exploration drilling and cutting output.

The oil industry that emerges from the coronavirus pandemic will likely have fewer companies because many will have been bought out, as has happened in past shakeups, one expert said at a conference held last month by the Wilson Center on COVID-19 impacts in the Arctic.

“The big fish eat the little fish, the vulnerable fish,” Mark Myers, former head of the U.S. Geological Survey, the Alaska Division of Oil and Gas and a past chancellor for research at UAF, said at the online conference.

There will be little incentive for exploration for an extended period, he predicted, as companies that are able to do so will buy new reserves instead of drilling for them.

Within Alaska, the big discoveries recently announced on the western side of the North Slope, in the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska and adjacent state land, are likely to go forward, Myers said. To the east, however, the situation is will probably be different, he said.

“New exploration projects, new areas open like the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, may not see the same level of interest they would have seen in other venues,” he said.

SAExploration is under federal and state investigation for possible financial misstatements. It has new leadership but said in a recent financial disclosure that results of the investigations “could include sanctions or other actions against us and our officers and directors, civil lawsuits, and penalties.”

And Balash is no longer in a position to preside over any ANWR lease sale. He left Interior for a job with Oil Search, an Australian company planning large developments on the western side of the North Slope. Those developments are currently on hold; Oil Search in March suspended all its work except that needed to maintain operations at producing oil and gas sites in Papua New Guinea.