Ships are venturing closer to North Pole thanks to climate change

Researchers have shown that ship traffic in the Arctic between 2009 and 2016 has moved north and east.

Since the early 2000s, scientists have observed historical records being set, then set again in the Arctic as temperatures warm and sea ice continues to shrink. Last month, Arctic sea ice was 7.3 percent below average, landing it in the No. 2 spot of the smallest extent of sea ice during March. From 2015 to 2018, the planet has witnessed four of the lowest peak Arctic sea ice extents in recorded history.

March 2018 Arctic sea ice extent was 7.3% below average—the 2nd smallest extent on record for the month: https://t.co/ZsdqKsFXEy #StateOfClimate pic.twitter.com/SEuq0UM9J3

— NOAA NCEI Climate (@NOAANCEIclimate) April 18, 2018

Shipping businesses and national leaders are paying attention to this decline.

While a lack of sea ice has started to affect some indigenous hunters and wildlife in the area, it could also clear up some vital shipping passages in the Arctic, including the Northwest Passage and Northern Sea Route. Traveling these routes could save shipping businesses both time and money, as they are far shorter than the current routes between Asia, Europe and North America.

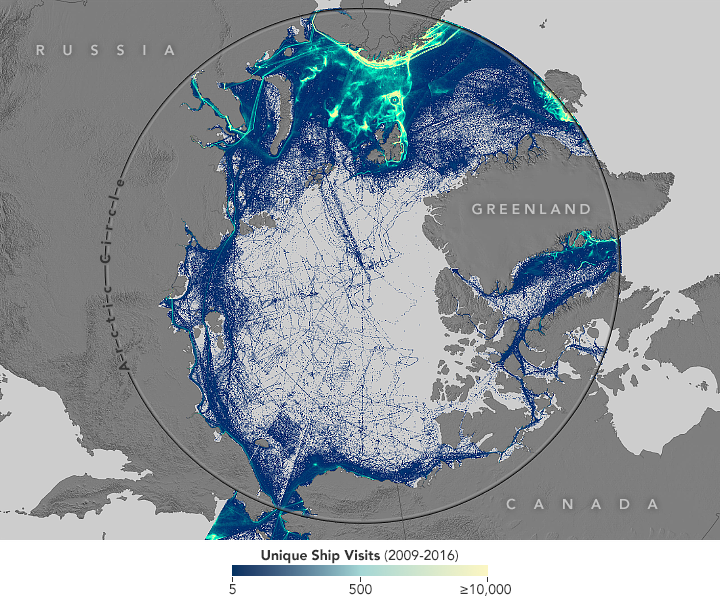

To illustrate how this decrease in winter sea ice is affecting the shipping industry, two professors recently released a map of unique ship visits to the Arctic between Sep 1, 2009, and Dec 31, 2016 (see above). Using millions of data points from Automatic Identification System signals from ships, Paul Berkman from Tufts University and Greg Fisk from Woods Hole Research Center plotted them on a map while also comparing them against sea ice data from the National Snow and Ice Data Center.

The data show that the average center of shipping activity in the region has moved closer to the North Pole — 300 kilometers north and east — since 2009, into waters that were once unnavigable. They also observed that there were more smaller ships like fishing vessels traversing farther north, and ships, in general, were encountering ice more often.

In an interview with Pacific Standard, Berkman said he hopes that this information will inform Arctic nations of the infrastructure needed as more ships travel north in the winter—increasing the chance of a spill or rescue operation.

The U.S. and Canada have conducted winter exercises for oil spills and rescues, and just last week the International Maritime Organization agreed to ban the use of the highly polluting heavy fuel oil in the Arctic.

“Knowing where ships are and how they’re increasing over time is necessary for nations to understand where to place their investments in terms of infrastructure development,” Berkman told Pacific Standard.