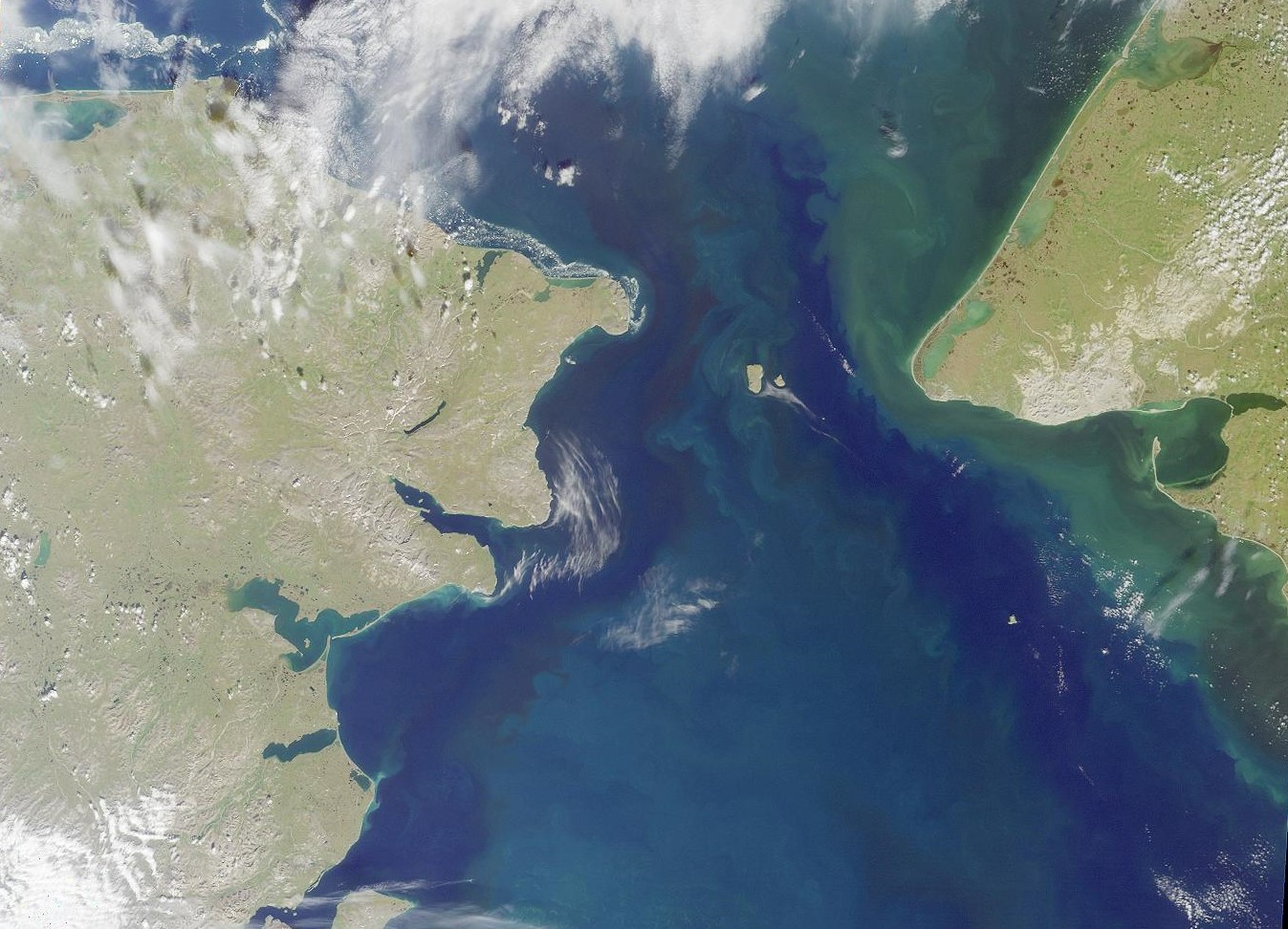

Study: Erosion has made the Bering Strait a meter deeper on the Alaska side than it used to be

A mapping project uses new data and applies new technology to old data to get more precise measurements in the critical Pacific gateway to the Arctic Ocean

The narrow channel of water that separates Alaska from Russia is a little bigger than it used to be, new analysis shows.

A research project found that the Bering Strait is at least a meter deeper on the Alaska side than previously believed, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center. The project evaluated new and old bathymetric surveys, applying modern technology to the latter to more accurately pinpoint locations.

The change is from erosion that took place between 1950 and 2010 and was likely the result of increasing flows of water through the strait, said a newly published study about the project, which NOAA describes as providing the first detailed analysis of the eastern Bering Strait’s seafloor.

“It’s the water, the fast currents, we think, that’s causing this erosion,” said Mark Zimmerman, a NOAA Alaska Fisheries Science Center biologist who is the lead author of the study.

The erosion has increased the underwater size of the strait by about 2%, Zimmerman said.

Increased water flow through the Bering Strait is well-documented through a long-term mooring program managed by the University of Washington oceanographer Rebecca Woodgate, a study coauthor. The program deploys instruments that are temporarily anchored to the sea floor, with floats and scientific sensors placed at various levels of the water column to collect data.

Woodgate’s moorings have been placed in the strait annually since 1990. With them, she and her colleagues have measured a steady increase of water flow northward, a trend likely linked to a longer open-water period without sea ice.

While currents likely caused the erosion, the extra space opened by the erosion could in turn affect currents in the future. The increase in depth might “form a positive feedback loop, exacerbating an established trend of treater northward throughflow in recent decades with significant climate change implications,” the study concluded.

For Zimmerman, who started the project in 2015 after meeting up with Woodgate and discussing her mooring work, the Bering Strait’s significance was a revelation.

“I was just blown away,” he said. “It’s basically the seam of the whole world here.”

He listed some geographic distinctions.

The Russian side, Chukotka’s Cape Dezhnev, is the easternmost point of land in Asia; on the Alaska side, Cape Prince of Wales is the westernmost point of landmass in North America. Within the 2.4 miles that separate the two tiny islands in the center of the strait, Russia’s Big Diomede and Alaska’s Little Diomede, lies the International Date Line. On Alaska’s Seward Peninsula, which points out to the strait, is the northern tip of the Continental Divide, the mountain spine that runs all the way to the southern tip of South America, and Cape Prince of Wales is at the end of another mountain feature called the Arctic Divide, which separates waters that drain into the Arctic Ocean from those that drain farther south.

The strait is also near the Arctic Circle and very close to the 180-degree longitude point, which is the opposite side of Greenwich, England, the designated 0 longitude site, Zimmerman noted.

The strait is a crucial spot biologically, too. It is the migration route for various species, from deep-swimming whales to long-distance traveling seabirds. Along with being the site for the flow of water and heat in the summer, it is the point where winter freeze-up allows formation of sea ice to spread from the Chukchi Sea to the Bering Sea.

Climate change is affecting that dynamic. Research led by Seth Danielson, a University of Alaska Fairbanks oceanographer, has found that the transfer of heat through the strait increased dramatically in recent years; as a result, the Chukchi Sea has warmed significantly over decades, a change that affects the entire Arctic.

The strait holds an important place in geologic history because it was a land link between continents at various times in past ages. That led to one surprising discovery in Zimmerman’s study: The identification on the seafloor channel near three larger channels that extend out of Alaska’s Norton Sound. Taken together, the channels appear to be the product of paleodrainages, which are the remnants of ancient rivers that are now covered with modern sediments. These paleodrainages would have been formed by a river or rivers that flowed when the strait was part of a land bridge connecting Asia to North America.

The last time the land bridge emerged was about 37,500 years ago, according to recent research, and it became submerged again between 11,000 and 13,000 years ago.

The strait is significant in human history and is currently a spot of geopolitical tension.

Cooperative research about the Russian side of the strait, including any potential work on this project, has been halted by the fallout of Russia’s war in Ukraine.

In past years, Woodgate maintained moorings on the Russian side, and she also worked at times with Russian colleagues, Zimmerman said. “But that was a while ago, and right now I think we’re not really in a good situation with sharing things,” he said. “We’re not allowed over there.”

In his follow-up work, Zimmerman is mapping the Chukchi Sea and Kotzebue Sound, a region where datasets are sparser than in the Bering Strait.

In general, Alaska needs much more seafloor mapping, he said, but the older datasets can be useful toward that end. In many cases, old data has been digitized incorrectly, and new technology that is more precise about latitude and longitude can be applied to overcome those flaws, he said.

“And then it fits,” he said. “It’s like a jigsaw puzzle.”

Alaska Beacon is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Alaska Beacon maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Andrew Kitchenman for questions: in**@al**********.com. Follow Alaska Beacon on Facebook and Twitter.

You can read the original here.