Study finds record amount of microplastics in Arctic sea ice

Ice cores from the Transpolar Drift Stream contained pollution from many sources, including cigarette filters, paint and nylon.

The Arctic may be thousands of miles from the planet’s largest cities and fastest booming populations, but that doesn’t mean it’s free of human junk.

A new study looking at microplastics in Arctic sea ice recently published in the journal Nature Communications found a record amount of the microplastics in the ice, surprising even veteran scientists contributing to the research.

Lead by Ilka Peeken, a biologist with the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany, the researchers wanted to identify any “sinks” where large amounts of small plastic debris in the ocean may be concentrated. Right now, scientists only know where 1 percent of these contaminants are located — at the sea surface.

“There are important unidentified sinks, which we try to find by sampling all spheres in our study area, from the sea surface, through the water column, down to the deep ocean floor,” Melanie Bergmann, a co-author of the study, wrote in an email.

This also included sea ice. Previous studies have shown that Arctic waters near Svalbard had high numbers of microplastics, defined as any plastic particle smaller than five millimeters, or about the size of a pencil eraser. Microplastics can come from a variety of sources, both land and sea. They can be the result of larger plastics degrading in the ocean, or fragments of tires and synthetic textiles floating into the ocean or trickling down sewer networks.

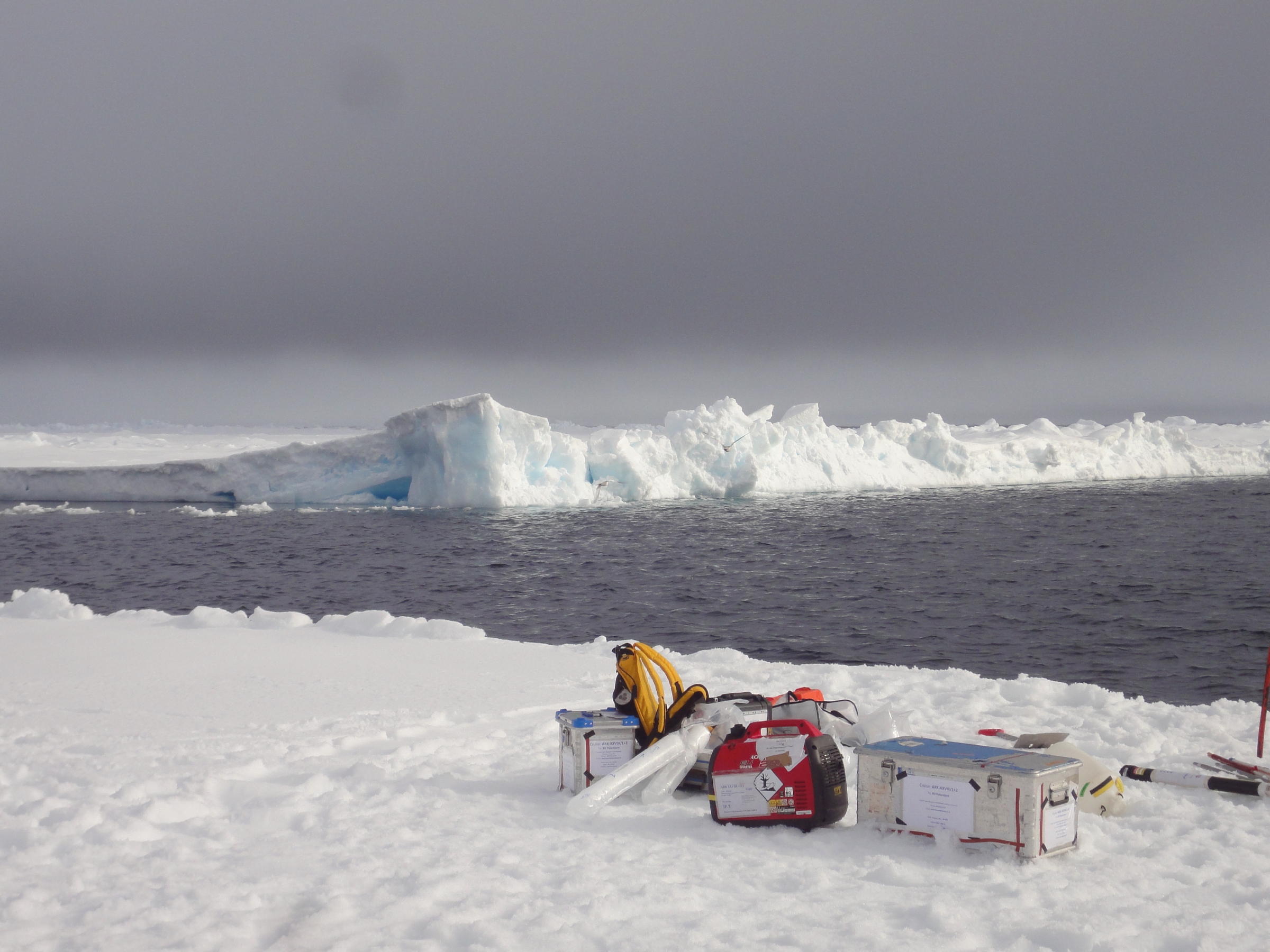

Sailing on the research icebreaker Polarstern in 2014 and 2015, the researchers collected ice samples from five areas in the Transpolar Drift Stream, a major ocean current that transports sea ice from Russia’s Arctic coast and deposits it near the east coast of Greenland.

The team then used Imaging FTIR to detect plastic particles in the sea ice—the first time this technique has been used to analyze sea ice cores layer by layer. Using this method, the researchers were able to spot superfine microplastics, as tiny as one-sixth the diameter of a strand of hair. This explains why the researchers found such high microplastic concentrations compared to past studies that didn’t use Imaging FTIR.

“This is important, as 67 percent of the particles were smaller than 50 micrometers,” wrote Bergmann.

While the concentration of microplastics varied widely in the five ice cores sampled, the highest was found in an ice core from Fram Strait between Greenland and Svalbard, containing 12,000 microplastic particles per liter. The lowest levels were detected in a sample from north of Svalbard, with 1,100 microplastic particles per liter.

“We did not expect to find such high concentrations, especially as we excluded fibers for methodological reasons, which accounted for most of the particles detected in the earlier study [that didn’t use Imaging FTIR],” wrote Bergmann.

The researchers also looked at what kind of particles were clogging up the ice. In total, they found 17 different kinds of plastics in the samples, with the most common including packaging materials, cellulose acetate from cigarette filters, paints and nylon.

These plastics could be from sources both in the Arctic and below. The researchers think that the nylon and paints, for example, could be coming from Arctic ships’ paints and fishing nets, while other materials like polyethylene from packaging material could have been transported from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

Once these particles make their way to the Arctic, they are being picked up and transported from one spot to the other. In dissecting the sea ice samples, the researchers found that the number of microplastics and the kind of microplastics could vary from one layer to the next. This suggests that the sea ice floes could be picking up microplastics in one location, then floating to another and picking up a different type, or amount, of microplastics there.

This finding is backed by another study that found polluted sea ice is moving faster between Arctic destinations, spreading pollution farther in the region.

“We know that long-range transport occurs with chemical pollutants, and this is why we see such high concentrations of contaminants at the top of polar foodwebs,” Chelsea Rochman, assistant professor at University of Toronto and expert in ocean and freshwater pollutants, wrote in an email. “For microplastics, we should be thinking along the same lines.”

While research behind microplastics has recently been growing, it’s still unclear how much of a health effect they have on both humans and marine life. But, the small size of many of the particles detected in the study means that they can be consumed by even the smallest organisms in the ecosystem.

Scientists think these particles may crowd the stomachs of animals, causing them to eat less, or change their behaviors or fertility.

“Although we still have a lot to learn about the effects of microplastics, there is enough evidence for concern — especially in such a vulnerable and remote ecosystem,” Rochman wrote.

And as shipping and fishing are predicted to increase in the Arctic, the presence of microplastics is expected to increase, too — even while melting ice releases more of the particles into the environment.

“We often think about methane releases with ice melting, but now we should also be considering microplastics. It seems sea ice was an ultimate sink, and that melting is altering that fate,” Rochman wrote.

Correction: An earlier version of this article mistakenly attributed quotes from Melanie Bergmann to Ilka Peeken. The article has been updated to correct the attributions.