Styrofoam igloos: A 1950s cure for the Inuit housing crisis

The shelters were eventually abandoned for more modern housing typical of southern Canada — which in turn caused housing problems that Nunavut is still addressing today.

Content warning: This piece contains an offensive term applied to some Indigenous Arctic peoples in the quotes from historical news coverage.

The COVID-19 pandemic and outbreaks in several communities across Nunavut have brought the Inuit housing crisis into focus. Inadequate and unsafe housing is endemic in many Inuit communities and has been blamed for poor health outcomes and susceptibility to infectious disease for decades.

And these problems have historical roots. Canada has been running federal government housing programs for 65 years in the North, including experimental Styrofoam igloos that were tested at Kinngait, Nunavut from 1956 to 1960.

The only reporting of the Styrofoam igloo project was in the children’s section of The Age, a newspaper in Melbourne, Australia on Sept. 9, 1960. The headline read: “Eskimos Find Plastic Igloo Better Than Snow Houses!” The article informed its young readers that the plastic version of the traditional Inuit housing structure was made from 18 inch by 36 inch Styrofoam blocks, held together by wooden meat skewers and adhesive.

The idea of housing people in Styrofoam huts seems laughably inadequate and even callous today, particularly when compared to housing standards for non-Indigenous Canadians. But the use of Styrofoam igloos is one of the few instances where the Canadian government tried providing Inuit with culturally sensitive housing.

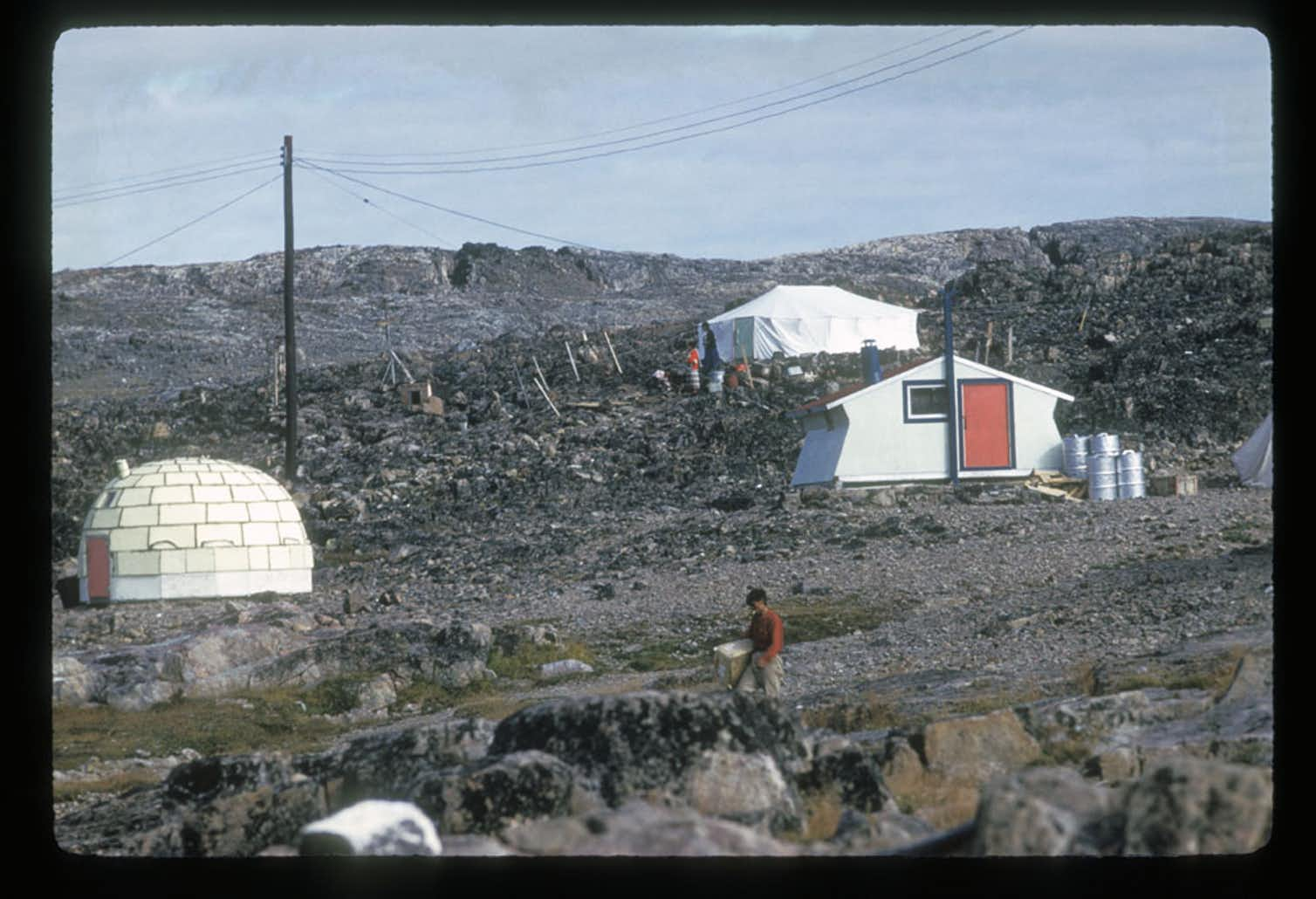

(Library and Archives Canada / National Film Board of Canada fonds / a114847)

Where did Styrofoam igloos come from?

Until the 1950s, it was federal policy that Inuit communities should continue their traditional ways of life with little interference. By 1955, however, there was a growing consensus that the government should provide a basic standard of living to all people living in Canada, convincing the government to change its policy.

Over the next five years, a number of experimental housing structures were tested in Inuit communities, including the Styrofoam igloos, Styrofoam quonset-style huts built in Iqaluit, and double-wall canvas tents. These projects were intended to solve high instances of illness and infant mortality associated with traditional self-built structures while maintaining existing forms of Inuit housing.

The Styrofoam igloos were the brainchild of James Houston of the Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources, who, according to The Age, came upon the idea of using Styrofoam, a petroleum-based product developed in the 1940s, to build a more moisture resistant igloo.

An Inuit man named Pitsulak, who was “famous as a fast builder of snow igloos,” The Age wrote, was brought south to Ottawa to cut the Styrofoam blocks for a test igloo, built “on a circular floor of two layers of plywood with Styrofoam inlaid between them.” The resulting 18-foot (5.5 meter) diameter structure was then disassembled, shipped to Kinngait and reassembled by Pitsulak.

Designed to fit traditional mobility

The Styrofoam igloos and other housing models tested in the 1950s were designed to fit in with traditional Inuit mobility, subsistence practices and mimic existing forms of Inuit housing. They were also developed by people with experience living and working in the Arctic. Houston had travelled throughout the Canadian Arctic and regularly visited Inuit communities as a promoter of Inuit art and printmaking. He considered himself familiar with Inuit housing needs. The involvement of Pitsulak also brought significant knowledge and experience to the project.

The Styrofoam igloos are also a reflection of the post-war ideology of “high modernity,” a belief that science and technology could be used for social benefit. “Suddenly the white man jumped ahead,” The Age declared, producing a Styrofoam igloo “so superior to the one of snow blocks … that the Eskimo has even praised the efficiency of the new invention.”

But what the Inuit community at Kinngait actually thought of the plastic structures is unknown. And it was exactly because the Styrofoam igloos were designed to align with Inuit culture that they were discontinued.

At the end of the 1950s, the government had begun to encourage Inuit communities to abandon the mobility and subsistence practices that culturally sensitive housing supported, and live in permanent settlements where they believed it would be easier to administer social programs and bolster Canada’s Arctic sovereignty claims.

The structures also failed to meet cost-efficiency and durability standards and did not conform to national building codes.

(Library and Archives Canada / Rosemary Gilliat Eaton fonds / e010835896 / Credit: Rosemary Gilliat Eaton)

The case for relevant housing

Housing built in Inuit communities after 1960 mirrored structures found commonly in Canada’s south. But this form of housing has proven ill-suited to Inuit needs.

Early models lacked space for butchering, storing food, repairing hunting equipment and were not built to withstand Arctic weather. Housing designed for southern families was ill-suited to Inuit cultural values like extended family cohesion and preference for open domestic space. Structures were also quickly over-crowded and failed to solve health concerns.

A 2017 Senate report showed that many of these issues persist in Inuit communities, with structures similar to those built in the ‘50s and ’60s still being occupied today. The COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated the issue.

[Read more: Housing is health: Coronavirus highlights the dangers of the housing crisis in Canada’s North]

The Styrofoam igloos may not have been “Better Than Snow Houses,” as The Age boldly stated, but they are an eccentric example of what can happen when Inuit housing projects are developed with cultural sensitivity and lived experience in mind. Solving the Inuit housing crisis will require cultural consultation and well-funded housing that once again reflects Inuit needs.

Scott Dumonceaux is Canada Research Chair in the Study of the Canadian North Postdoctoral Fellow in the School for the Study of Canada at Trent University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.