Svalbard Treaty doesn’t apply beyond coastal waters, signals Norwegian high-court ruling in snow crab case

Because crabs move on Norway’s continental shelf, not in the international waters above it, Oslo may limit who can catch them, according to a unanimous court ruling.

A Supreme Court of Norway ruling Thursday appears to support Oslo’s claim that it alone has the right to grant permission to exploit resources on the seabed surrounding Svalbard.

The unanimous decision by 11 Høyesterett justices applies directly to crab fishing, but the ruling could provide a precedent that could be used in cases involving other resources on the continental shelf, including oil and minerals. (See ‘Equal justice under water’ in this week’s Week Ahead feature for more background.)

It can also be seen as strengthening Norway’s argument that the 1920 Svalbard Treaty, which gives countries the right to conduct economic activity in the Oslo-administered territory, does not apply beyond its territorial waters, extending 12 nautical miles (22 kilometers) from shore.

[Norway risks having to share Svalbard resources with the EU]

In the case decided today, the issue boiled down to a question of whether crabs, when they move, remain in contact with the seabed at all times, making them what is known, in legal terms, as a ‘sedentary’ species, or whether they, like fish, are caught in the water column.

If they can be defined as the former, Norway argues, then they are resource that belongs to its continental shelf, and thus cannot be exploited without its permission.

The Høyesterett decision upholds a lower court’s ruling that Norwegian officials acted properly when in January 2017, they fined a Latvian fishing crew and seized their boat, along with its load of snow crabs after they were stopped for fishing without a permit.

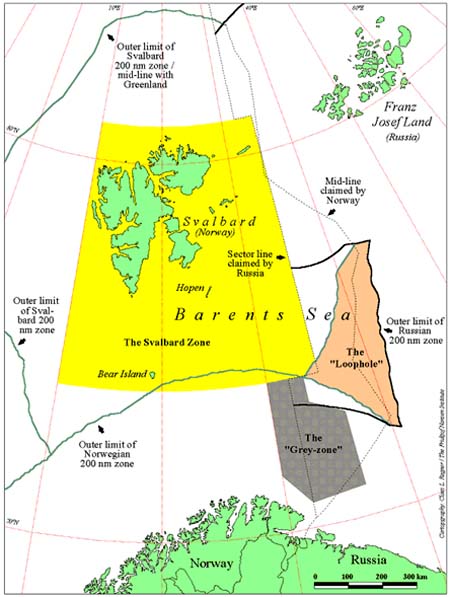

The crew of the Latvian vessel admitted to not having a Norwegian permit, but argued that their EU-issued fishing license was sufficient, because they had been operating in a sliver of international water in the Barents Sea beyond the territorial waters Norway, on the one side, and Russia, on the other. (See map below.)

Oslo and Brussels have been at odds over snow crab fishing since 2015, when the species first began to appear near Svalbard in large numbers. Oslo has taken a cautious approach to opening snow crab fishing, choosing, for the time being, to grant permits only to Norwegian boats.

Although the EU disagrees with the practice, the European Commission, the union’s executive arm, has chosen to avoid a direct conflict. However, several member states, led by Poland and Latvia, have chosen to openly challenge the practice, arguing that it discriminates against foreign fishermen.

It is unlikely that today’s decision will change how the commission has chosen to deal with the issue, according to Andreas Raspotnik, an academic specialising in the EU’s Arctic policy, although he believes the discussion about where the the century-old Svalbard Treaty’s jurisdiction ends may be a sign it is showing its age.

“What’s at issue here is whether the treaty applies to water as well as to land. Norway says no, but it appears they are quite alone in that position.”