Svalbard’s ‘Doomsday’ seed vault marks 10th anniversary with upgrades to protect it from climate change

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault celebrates its first decade in operation by accepting its millionth sample—and a grant for work to keep those samples safe despite melting permafrost.

On Monday, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault marks its 10th anniversary by accepting new deposits from 26 gene banks around the world.

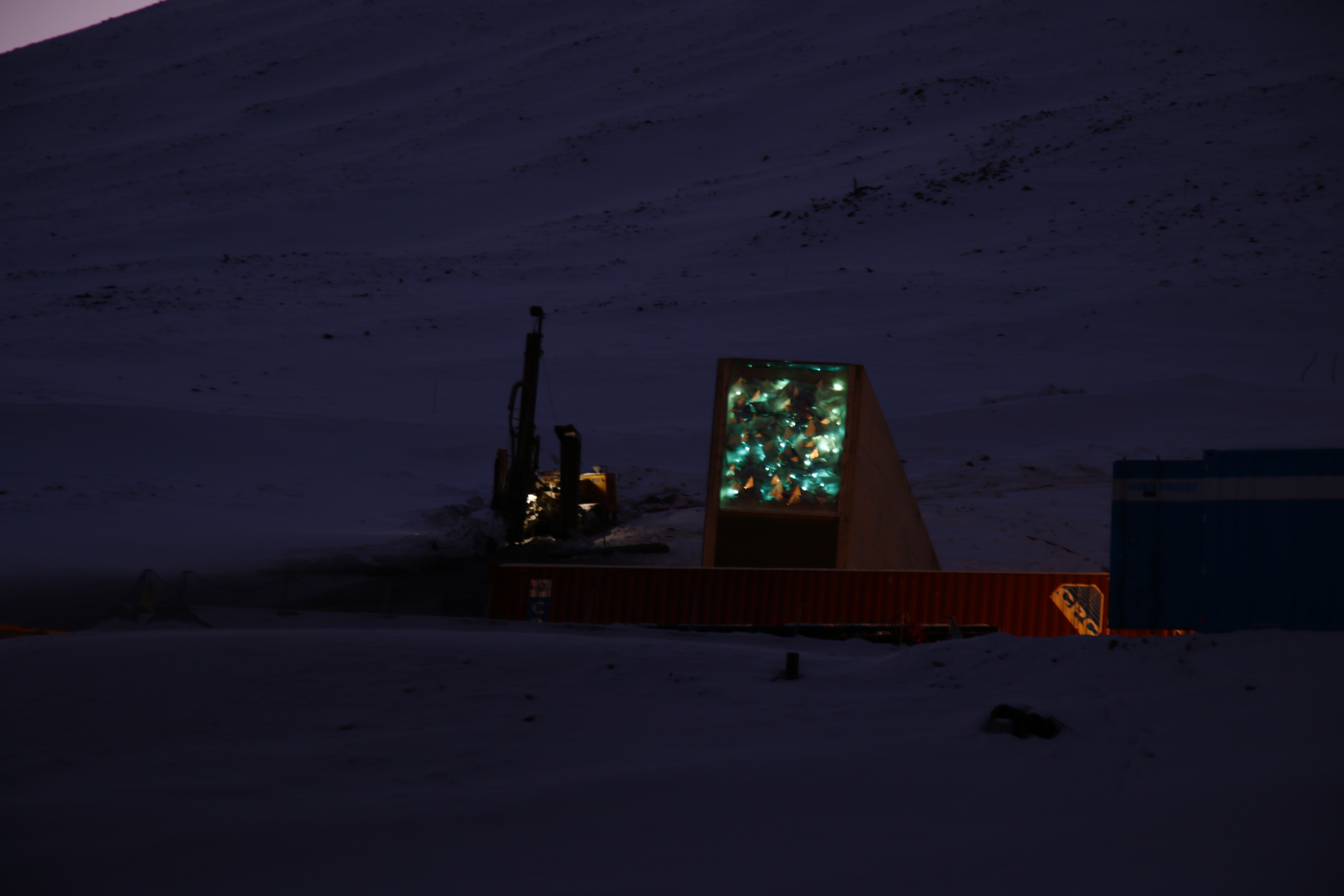

Earlier this month, construction equipment blocked the entrance to the so-called “Doomsday” vault on the Norwegian Arctic archipelago in preparation for critical upgrades after the facility’s entrance flooded last spring because of thawing permafrost. Last week, the Norwegian government announced a major grant to fund those improvements.

The vault accepts the seeds — and the grant — against a backdrop of climate change and geopolitical uncertainty that suggests it will be increasingly relevant in the future.

The seed vault opened in 2008 in a former Svalbard coal mine shaft to provide a backup seed sample catalogue for the more than 1,700 seed gene banks worldwide that store collections of food crops for safekeeping. If seed samples from those banks were lost due to natural catastrophes, war, or even a freezer malfunction, backup samples stored in the Svalbard vault could keep crop varieties from going extinct. The vault, which is managed by the Norwegian government, Nordic Genetic Resource Center, and the Crop Trust, housed roughly 300,000 seed samples at its opening. By early 2018, it held more than 983,000 samples from 73 countries around the world, including 150,000 samples of rice, 140,000 samples of wheat, and 70,000 of barley, as well as the wild relatives of key food crops. The deposits made at the end of this month will push the vault past the 1 million mark.

“The seed vault it is not a very complicated project; it’s not rocket science. It’s just about storing seeds in a frozen hole in the Arctic,” says Åsmund Asdal, coordinator of operation and management for the seed vault, who works to negotiate with gene banks and facilitate shipments of seeds. At the same time, the current geopolitical climate could lend ever more relevance to the vault’s mission. In 2015, agronomists with the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas in Syria became the first to make a withdrawal after losing access to seed samples stored in Aleppo during that nation’s civil war. Meanwhile, in early 2018, after an escalation of threats between the United States and North Korea over nuclear missiles, and an accidental warning that one was headed for Hawaii, the Doomsday Clock, a symbol which represents the likelihood of a man-made global catastrophe, ticked 30 seconds closer to midnight.

Norway, alternatively, exemplifies the relative peace and stability of the Arctic.

“Norway has a high level of confidence all over the world; that countries from east and west, south and north, poor and rich, all trust Norway to take care of these seeds,” says Asdal.

Axel Diederichsen, curator of Plant Gene Resources of Canada, echoed Asdal’s sentiments over security. “Norway is not known to enter many conflicts and wars. It’s stable.”

But the same can’t be said for the permafrost underlying the vault. In 2016, an especially hot year in Svalbard, temperatures regularly approached 13 F degrees higher than normal, and surrounding permafrost began to thaw, flooding the entrance of the 100-meter long tunnel come spring 2017. Though the vault’s Svalbard location was specially chosen for its cool temperatures and permafrost, the seed storage facility itself remains refrigerated. “Not so many places in the world are more suitable than Svalbard,” says Asdal.

Last week, ahead of the anniversary celebrations, the Norwegian government proposed a grant of 100 million kroner (about $12.7 million) to upgrade the vault’s facilities in the face of an uncertain climate future. The grant will fund the construction of a new concrete access tunnel, with waterproof walls, as well as a service building to house emergency power and refrigerating units and other electrical equipment. The upgrades are meant satisfy concerns about the vault’s future ability to safely store seeds in a changing Arctic.

Canada will deposit 3,858 seed samples at the end of the month — about 15 boxes including about 155 different species. This will be the country’s seventh deposit.

“The seed vault is an important symbol of the value of plant genetic resources, plant breeding, food production,” says Asdal. “We can use the seed vault in order convince politicians, organizations, and the public that they should invest money and effort into this conservation initiative.”

The seed vault has served as inspiration for other doomsday storage endeavors, too. Last spring, Norwegian tech company Piql announced plans to develop an “Arctic World Archive,” that will store digitized copies of historically important documents and literature in an old coal mine shaft on the same mountain slope as the seed vault.