A test project will use polymers to try to unlock untapped heavy oil on Alaska’s North Slope

U.S. Department of Energy, the University of Alaska Fairbanks and Hilcorp Energy Company will test out a new technique to reach the difficult oil that makes up a large part of Alaska's North Slope reserves.

Overlaying the prolific oil reservoirs that have fed production of the Alaska North Slope oil fields for the past four decades is a completely different and untapped resource — tens of billions of barrels of heavy oil in shallower geologic formations that have, at least so far, confounded the energy companies operating in that Arctic region.

Now the U.S. Department of Energy, the University of Alaska Fairbanks and Hilcorp Energy Company are teaming up to test a method that might unlock that heavy oil.

The DOE’s National Energy Technology Laboratory on Wednesday announced a $9.5 million pilot program that will use an alternative material to try to lift the heavy oil out of the rock. It will be the first polymer flood ever conducted on an oil well in the United States, said Jared Ciferno, oil and gas technology manager for the National Energy Technology Laboratory and one of several DOE officials attending the Alaska National Lab Day events held at UAF on May 30 and 31.

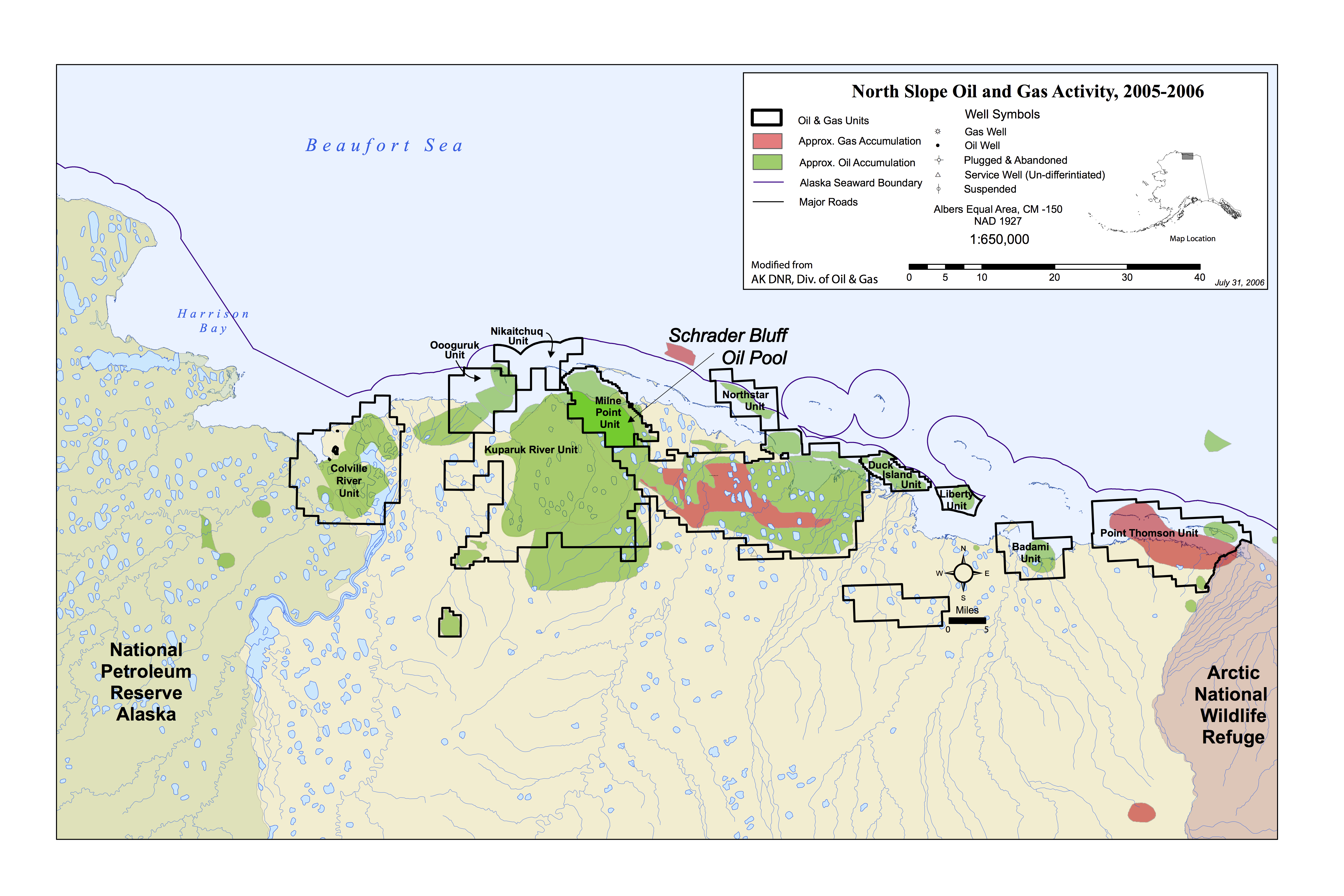

The test drilling will be at the Milne Point, a field that Hilcorp operates, and will be applied to oil from the Schrader Bluff formation, which overlays the Kuparuk River formation. The Shrader Bluff formation holds 15 billion to 20 billion barrels of heavy oil, according to the DOE; another formation, West Sak, holds similarly vast amounts of heavy oil, almost all of it too heavy to be produced with current technology, according to the department.

There has been only a small amount of production out of either the Schrader Bluff or West Sak reservoirs, and that has been limited to the very lightest oil that exists there.

The DOE-funded test program seeks to change that history.

“This field test will advance knowledge of heavy oil’s production viability using polymer floods at ANS and across the United States. Success at this location will strengthen the viability of the Trans Alaska Pipeline System in the upcoming decade and improve royalty and other fees to the U.S. taxpayer,” the National Energy Technology Laboratory said in a statement.

The DOE is providing about $7 million for the project; the other $2.58 million will come from other sources, the department said.

Hilcorp has strong incentives for figuring out how to produce heavy oil, the company’s top Alaska official said.

Heavy oil accounts for 45 percent of Hilcorp’s total North Slope oil reserves, John Barnes, the company’s senior vice president for Alaska, said Wednesday at the National Lab Day conference. Conventional light oil — described as water-like in its flow — accounts for only 34 percent but has supplied 92 percent of the company’s production, Barnes said, and other North Slope companies are in a similar position. Hilcorp and other companies are producing small amounts of oil classified as “viscous,” which has been described as having the consistency of maple syrup.

In contrast, the North Slope’s heavy oil is more like ketchup, Barnes said. The usual methods of oil recovery do not work well with such thick oil, he said.

The typical recovery pattern is to push oil out of the ground with pressure, then augment the reservoir pressure and, once that pressure is depleted, use water flooding to lift the oil, Barnes said.

“The issue is that with these heavy viscous oils, it doesn’t push very well,” he said. “Imagine trying to pump oil through ketchup.”

The DOE-funded test will combine polymers with water to try to create a new fluid to flood the reservoir, Barnes said.

Even if the technology works, applying it will be challenging, he said. Among the challenges are the logistics of bringing needed materials to the remote North Slope, he said. “How do you get polymer to the Slope?” he said. “If someone could figure out how to make polymer out of natural gas on the North Slope, that would be a winner. Otherwise, we have to ship it up.”

Yereth Rosen is a 2018 Alicia Patterson Foundation fellow.