Thaw along Alaska’s Dalton Highway shows how vulnerable infrastructure on permafrost is

“Unfortunately, there’s no good, cheap solutions.”

Current models are probably underestimating how vulnerable Arctic infrastructure is to climate change, finds a new study that examined the heat-driven deterioration of the sole highway to the oil fields of Alaska’s North Slope.

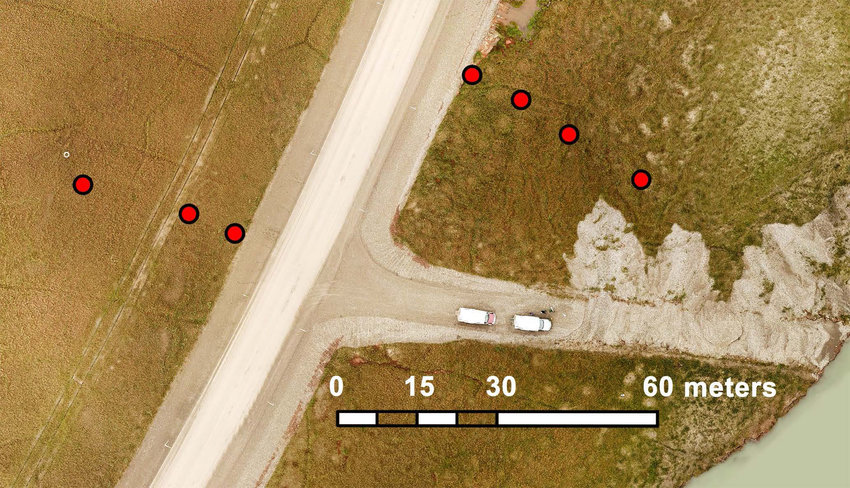

The study focused on a section of the Dalton Highway about 10 miles south of the Prudhoe Bay oil field — an area with permafrost that was once considered safely solid. There, the thaw is not just underneath the road but also on the sides, which means the thaw is moving not just vertically but also laterally, according to the study, published in The Cryosphere.

Rather than happening gradually as long-term climate change sends warmth down into the soil, the thaw is expected to happen in two phases, “an initial phase of slow and gradual thaw, followed by a strong increase in thawing rates after the exceedance of a critical ground warming.”

At this section of the Dalton Highway, that second phase of speedy thaw is triggered by the development of talik — year-round unfrozen ground — at the edge of the roadway.

Vladimir Romanovsky, a permafrost expert at the University of Alaska Fairbank and a co-author of the study, said the study suggests that continuing to operate critical infrastructure in permafrost areas, such as the 414-mile Dalton Highway, will be challenging.

“Unfortunately, there’s no good, cheap solutions,” he said.

What’s more, the mere existence of the road and the effects of its use help tip the scales toward thaw, Romanovsky said.

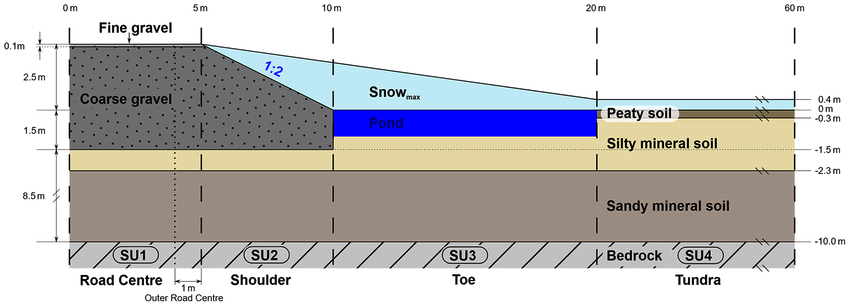

Snowplowing is a significant factor in permafrost thaw, Romanovsky said. The berms of snow piled up along the road serve as insulation in winter that keeps warmth in the ground, protected from the cold air.

Other factors are dust kicked up by traffic, which harms the tundra plants that insulate the ground from the summer heat and therefore act as natural permafrost protection, and water runoff, which is a “very strong agent” that carries heat into the soil, even more efficiently than warm air, Romanovsky said.

That lateral thaw is strongest in the first 10 or 20 meters on either side of the road, he said. But road-related thaw can extend up to 100 meters on either side, he said.

That interaction of the road with the permafrost might not have much been a problem in the past, when the soil at that site was hard–frozen at minus 8 degrees Celsius, Romanovsky said. As the soil has warmed to minus 4 degrees or above, however, it has become much more vulnerable to disturbance. “An increase of 2 or 3 or 4 degrees will bring it to zero,” he said.

Romanovsky knows the Dalton Highway well and has seen the changes to it. He has been driving up and down the highway since the early 1990s to measure permafrost temperatures.

Some attempts to shore up the highway have been successful, while others have backfired, he said.

“When they tried to put asphalt on it, it made the situation even worse,” he said. “In some places, the asphalt was removed.”

The study said lessons from northern section of the Dalton Highway should serve as a warning for future development, including planned development on the North Slope, which envisions yet more roads, oil pads and other structures atop of vulnerable permafrost that is edging toward a thaw threshold.

The results “underline that it is crucial to consider climate change effects when planning and constructing infrastructure on permafrost as a transition from a stable to a highly unstable state can well occur within the infrastructure’s service lifetime,” the study said. For the Dalton Highway study area, that transition could arrive in the coming decade, it said.

Romanovsky said he has also noticed changes to the trans-Alaska pipeline itself, which parallels the highway. Alyeska Pipeline Service Company, the consortium that operates the critical 800-mile artery that ships oil from the North Slope, has so far avoided any major permafrost-related disasters, thanks to lots of protective work, he said.

But the clock is ticking, he said.

“As some permafrost starts to thaw around the pipeline, other problems will develop,” he said.

Alyeska’s work includes a project this summer to refreeze a section of thawing hillside along the midpoint of the pipeline. The company is inserting 60 thermosyphons into the affected site, which is within the pipeline’s right-of-way, said Alyeska spokeswoman Michelle Egan. The thermosyphons are pipes that do precisely what their name suggests: “They draw heat from the ground,” Egan said.

The pipeline was built with such thermosyphons integrated into its design, but these new thermosyphons will be freestanding, according to the company’s plan. Creeping movement in the slope has already caused a few of the pipeline’s vertical supports to bend, and this year’s project is intended to “protect the integrity of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline

mainline from permafrost degradation,” said the company’s planning document that was submitted to the Alaska Department of Natural Resources.

Around the Arctic, permafrost thaw is recognized as a serious risk to existing infrastructure.

In northern Russia, 40 percent of buildings are showing thaw-related damage, Aleksandr Kozlov, the nation’s minister of natural resources, said in May.

For infrastructure in Canada’s Northwest Territories, a 2017 study concluded that permafrost thaw will cause CA$51 million a year in economic losses. The study, by the Northwest Territory’s Association of Communities, put the total foreseeable costs in the 33 communities at CA$1.3 billion.

In all, about 3.3 million people living across the Arctic are in communities where permafrost is expected to degrade and ultimately disappear by 2050, according to a study published earlier this year and authored by Swedish, Norwegian and German scientists.