The Arctic is ‘behaving so bizarrely.’ Here’s how some scientists explain that

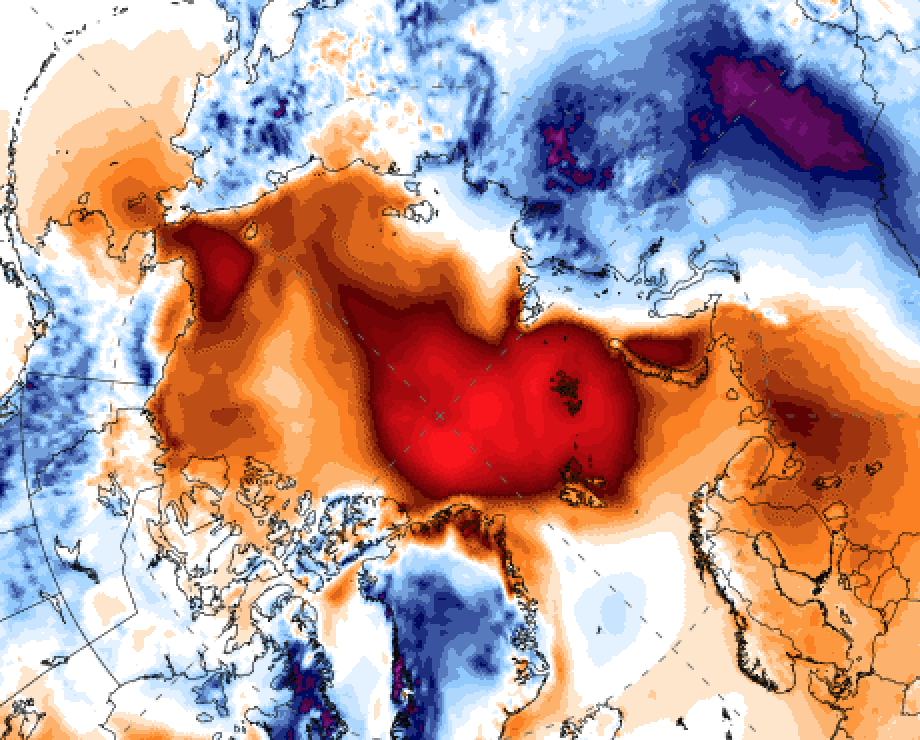

Last month, temperatures in the high Arctic spiked dramatically, some 36 degrees Fahrenheit above normal — a move that corresponded with record low levels of Arctic sea ice during a time of year when this ice is supposed to be expanding during the freezing polar night.

And now this week we’re seeing another huge burst of Arctic warmth. A buoy close to the North Pole just reported temperatures close to the freezing point of 32 degrees Fahrenheit (0 Celsius), which is 10s of degrees warmer than normal for this time of year. Although it isn’t clear yet, we could now be in for another period when sea ice either pauses its spread across the Arctic ocean, or reverses course entirely.

[Spiking temperatures in the Arctic startle scientists]

But these bursts of Arctic warmth don’t stand alone – last month, extremely warm North Pole temperatures corresponded with extremely cold temperatures over Siberia. This week, meanwhile, there are large bursts of un-seasonally cold air over Alaska and Siberia once again.

It is all looking rather consistent with an outlook that has been dubbed “Warm Arctic, Cold Continents” — a notion that remains scientifically contentious but, if accurate, is deeply consequential for how climate change could unfold in the Northern Hemisphere winter.

The core idea here begins with the fact that the Arctic is warming up faster than the mid-latitudes and the equator, and losing its characteristic floating sea ice cover in the process. This also changes the Arctic atmosphere, the theory goes, and these changes interact with large scale atmospheric patterns that affect our weather (phenomena like the jet stream and the polar vortex). The result can be a kind of swapping of the cold air masses of the Arctic with the warm air masses to the south of them. The Arctic then gets hot (relatively), and the mid-latitudes — including sometimes, as during the infamous “polar vortex” event of 2013-2014, the United States — get cold.

For now, these ideas aren’t accepted by all of the relevant scientists — but they definitely have a core group of supporters who are publishing, arguing, and citing recent events to advance their case. Scientists are gathering in Washington, D.C. in February to hash them out further — by which time, we’ll know more about just how much winter weather itself has given momentum to the conversation.

“We continue to see this Arctic behaving so bizarrely, I think we’re in for a very interesting winter,” said Francis.