The Arctic is getting hotter and rainier, the latest report card says

And the region's seasons are shifting, said researchers who prepared the 2022 report.

Seasons in the Arctic are shifting, and the region is getting hotter and rainier, according to an annual report card by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration that tracks climate change in the Arctic.

The air, land, and sea of the Arctic are warming quickly, and extreme weather events — including wildfires and storms like ex-typhoon Merbok — are becoming the new normal, NOAA scientists say.

The 17th report, by 147 authors from 11 countries, has new chapters on precipitation, shipping, birds, and communities in the Arctic — especially communities of the region’s Indigenous peoples.

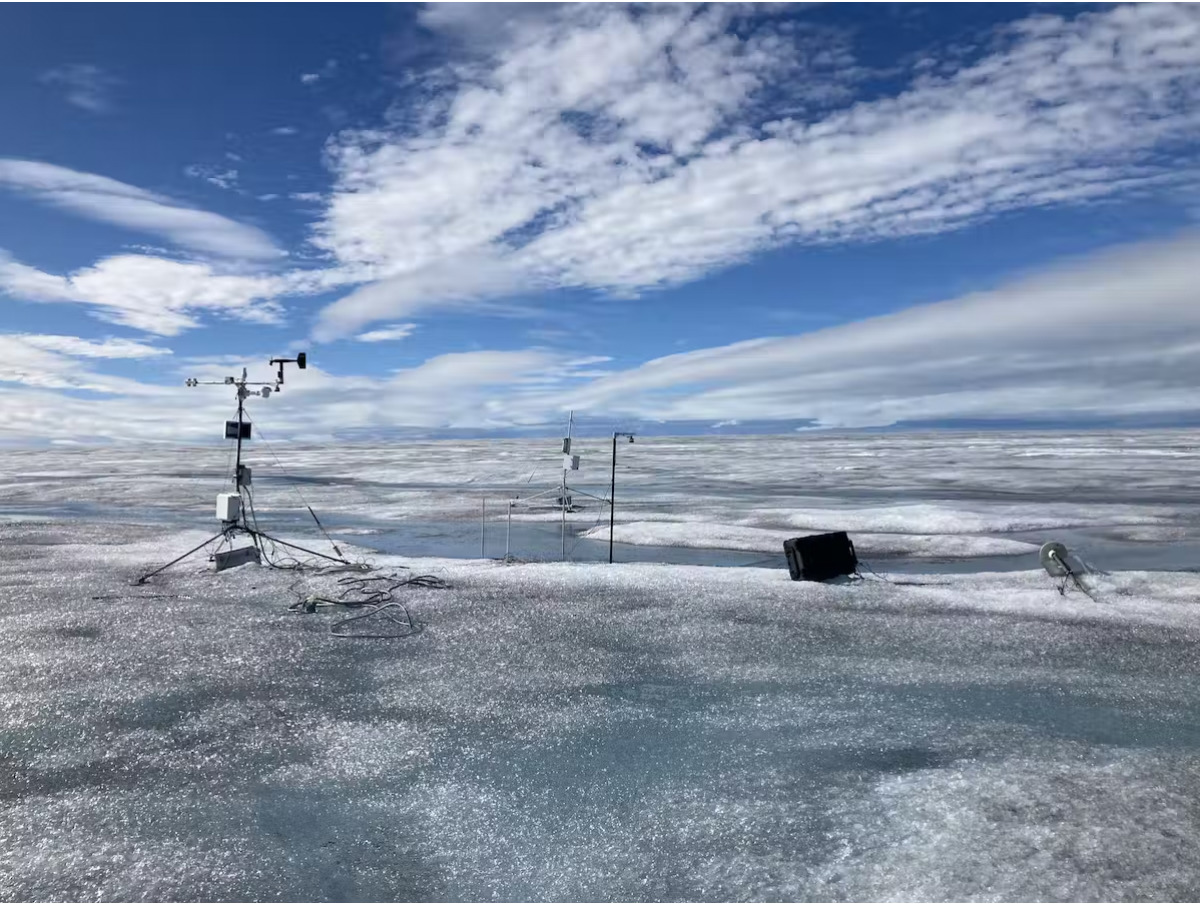

It continues to follow changes to air and ocean temperatures, sea ice, plankton, snow cover, the greening of the tundra and forest, and the Greenland ice sheet.

“The wolf is in the house,” NOAA Administrator Richard Spinrad said describing the immediacy of climate change risks in the region. Climate change is thawing permafrost and warping roads, melting ice and warming waters — with ripple effects for the seafood industry — as well as lengthening the fire season and forcing Indigenous communities to relocate, he said.

“Rapid warming in the Arctic is profoundly affecting the more than 400,000 Indigenous people who live there, and in many instances is upending their entire way of life,” he said.

Adding precipitation as a “vital sign” in the report was “a testament to the significant increase we’ve seen in precipitation events in the Arctic as the climate warms,” Spinrad said.

2022 was one of the wettest years on record across all seasons in the Arctic. It was the third wettest year in the past 72 years, since 1950, and the only years with more rain were 2018 and 2020.

“The transition is essentially occurring already,” said John Walsh, chief scientist at the International Arctic Research Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and lead author of the new chapter on precipitation. “In the next few decades, we’re going to see a transition from snow to rain, and rain will become the major part of the precipitation yearly over most of the fringes.” That trend may not hold for colder regions, he said, which may actually see more snowfall in winter.

But overall, snow is also vanishing more quickly in the Arctic.

“The snow season, especially in spring, is declining at a rate of nearly 20 percent per decade,” said Matthew Druckenmiller, lead editor of the Arctic Report Card and a research scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center.

Snow cover in June 2022 was unusually low. The North American Arctic saw its second-lowest snow cover in 56 years of keeping records, and the Eurasian Arctic saw its third lowest snow cover. While the accumulation of snow the previous winter was above average, early melt meant a lower snow cover overall.

Air temperatures in the Arctic were the sixth warmest this year since 1900, and the seven warmest years on record have all been in the past seven years.

The Greenland Ice Sheet lost ice for the 25th year in a row. “In early September of this year, 2022, the Greenland ice sheet experienced an unprecedented late-season melt event across 36 percent of its surface,” Druckenmiller said. Events like these are “challenging how researchers define the Greenland summer melt season,” he said. “Seasons are shifting in the Arctic.”

This year’s report also includes findings from NASA’s Oceans Melting Greenland mission confirming that rising ocean temperatures along the island’s continental shelf play a role in melting ice at the margins of the ice sheet, he said.

Earlier ice melt means there’s a longer growing season for algae. “Since 2003, primary productivity in the Eurasian Arctic has increased by 62 percent and in the Barents Sea by 18 percent,” said Karen Frey, a professor of geography at Clark University and author of the chapter on Arctic plankton blooms. “Monitoring changes in marine algae growth is important for understanding how upper levels of the marine food web, including fish, marine mammals, and seabirds, are impacted as well.”

This year’s report has a greater focus on Indigenous knowledge and leadership than previous years, Druckenmiller said. “This report card increasingly is looking to Arctic peoples to share how they understand, experience and deal with change — not only isolated events, like storms, but also the cumulative impact of Arctic and global change across years and increasingly across decades.”

“Our homes, livelihoods and physical safety are threatened by the rapid melting ice, thawing permafrost, increasing heat, wildfires and other changes tracked by the Arctic report card,” said Jackie Qataliña Schaeffer, director of climate initiatives for the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium and co-author of the chapter on Arctic communities.

But climate solutions created by Arctic residents could be relevant elsewhere as climate change affects other parts of the planet.

“We’re seeing the impacts of climate change happen first in polar regions,” Spinrad said. “We’re also seeing the ways in which communities, businesses and institutions are innovating and adapting to the effects of climate change.”

This article has been fact-checked by Arctic Today and Polar Research and Policy Initiative, with the support of the EMIF managed by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

Disclaimer: The sole responsibility for any content supported by the European Media and Information Fund lies with the author(s) and it may not necessarily reflect the positions of the EMIF and the Fund Partners, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and the European University Institute.