The COVID-19 pandemic has halted most US Arctic field research for 2020

“This will be a massive gap year.”

Seasonal scientific field work in the Arctic — from the Toolik Field Station on Alaska’s North Slope to ice core drilling in Greenland — is being postponed or cancelled this year because of the deadly COVID-19 pandemic.

Researchers hope that by putting off travel to the region, they will avoid spreading the disease in vulnerable rural communities and in field outposts with close living and working quarters. But the disruption will hinder a wide variety of ongoing studies, including research on ice sheets, glaciers, permafrost, plant and animal habitats, and ocean fisheries — research that underpins human understanding of global climate change and other vital scientific questions in the circumpolar North.

“The biggest impact is certainly the size and scale of projects that have been cancelled in this season,” said Simon Stephenson, head of the United States’ National Science Foundation Section for Arctic Sciences.

About 90 percent of 150 international Arctic projects funded by his agency, across the spectrum of natural, physical and social sciences, have cancelled their 2020 spring and summer field research expeditions, Stephenson said.

While some satellite and remote monitoring missions continue, Department of Energy and NASA officials said that much of their Arctic field research has also been delayed or cancelled for the 2020 season. NASA flights have been grounded, and two DOE observation sites for atmospheric and climate measurements in Alaska are operating at limited capacity, they said.

Most of the affected field work will be postponed until next year.

[US Coast Guard prepares for annual Arctic operations, but with coronavirus precautions]

Although it’s impossible to know the full extent of impacts yet, many experts believe the disruption will have serious detrimental impacts on the postponed and cancelled research.

“We can collect what data we absolutely have to and acknowledge this will be a massive gap year,” said Robert Foy, science and research director of the Alaska Fisheries Science Center, part of the federal National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “The reality is this is going to take years if not decades to address a gap the magnitude of this one in the Arctic,” he said.

“This research is important in observing how the environment changes from year to year, the sea ice distribution, the changing fish stocks, water temperature and chemistry, the migration of marine mammals, all of which are important to our understanding of the changing climate and evolving ecosystems,” John Farrell, the U.S. Arctic Research Commission’s executive director, said in an interview. “Without measurements for 2020 we have a gap in our understanding, and that gap is impossible to fill unless we have basic observations.”

Foy, Stephenson and other federal officials spoke at a two-day virtual conference last week on “COVID-19 Impacts in the Arctic,” sponsored by the U.S. Naval War College, the Wilson Center’s Polar Institute, and the U.S. Arctic Research Commission. More than 50 speakers broadly addressed the pandemic’s human health and economic impacts in Alaska and other Arctic regions, as well as the disruption to international Arctic scientific research.

The conference itself was a testament to the scope of research affected. Hastily organized while numerous conventional spring Arctic conferences were being cancelled, the online event drew more than 1,000 registrants with less than a month’s notice.

“Frankly I was surprised,” said Farrell, who was one of the conference’s organizers. “The conference showed a huge interruption in our ability to conduct science in the Arctic region, especially science that requires field work.”

[The coronavirus pandemic has shortened CCGS Amundsen’s Arctic research season]

The widespread cancellation of 2020 Arctic research expeditions stems mostly from concern that field research could help spread the deadly coronavirus into vulnerable communities there, as well as camps and ships where researchers live and work in crowded quarters. COVID-19 infections would be especially challenging to control in remote Arctic areas where medical care is extremely limited.

Some homes in rural Arctic communities lack running water, many families live in crowded households, and individuals may be more likely to have underlying medical conditions, making isolated Alaska populations particularly vulnerable to the quick spread of COVID-19, warned Anne Zink, chief medical officer for the state of Alaska. Indigenous Arctic communities have been hard hit by previous deadly disease outbreaks, including the 1918 Spanish flu, which wiped out whole villages in Alaska. “We all are aware of the history….To this day, people are still scared of disease from the 1918 epidemic,” said Kaare Erickson, North Slope science liaison for Alaska’s Ukpeagvik Iñupiat Corporation.

Thus far, COVID-19 restrictions in Alaska have kept cases to 408 and deaths to 10 (as of May 23), mostly in Anchorage and Fairbanks. There are still new and active cases, however, and, as the state begins to open up, health officials are concerned that out-of-state fishermen, tourists and visitors could increase spread of the virus. In Greenland, a strict lockdown kept COVID-19 cases to 11 people, all of whom have recovered.

Numerous scientists whose 2020 Arctic field work is cancelled voiced similar concerns: “The pandemic is widespread in the U.S., but there are no active cases now in Greenland. We don’t want to be the ones to inadvertently bring COVID-19 to Greenland,” Mary R. Albert, Dartmouth professor of engineering, said in an interview.

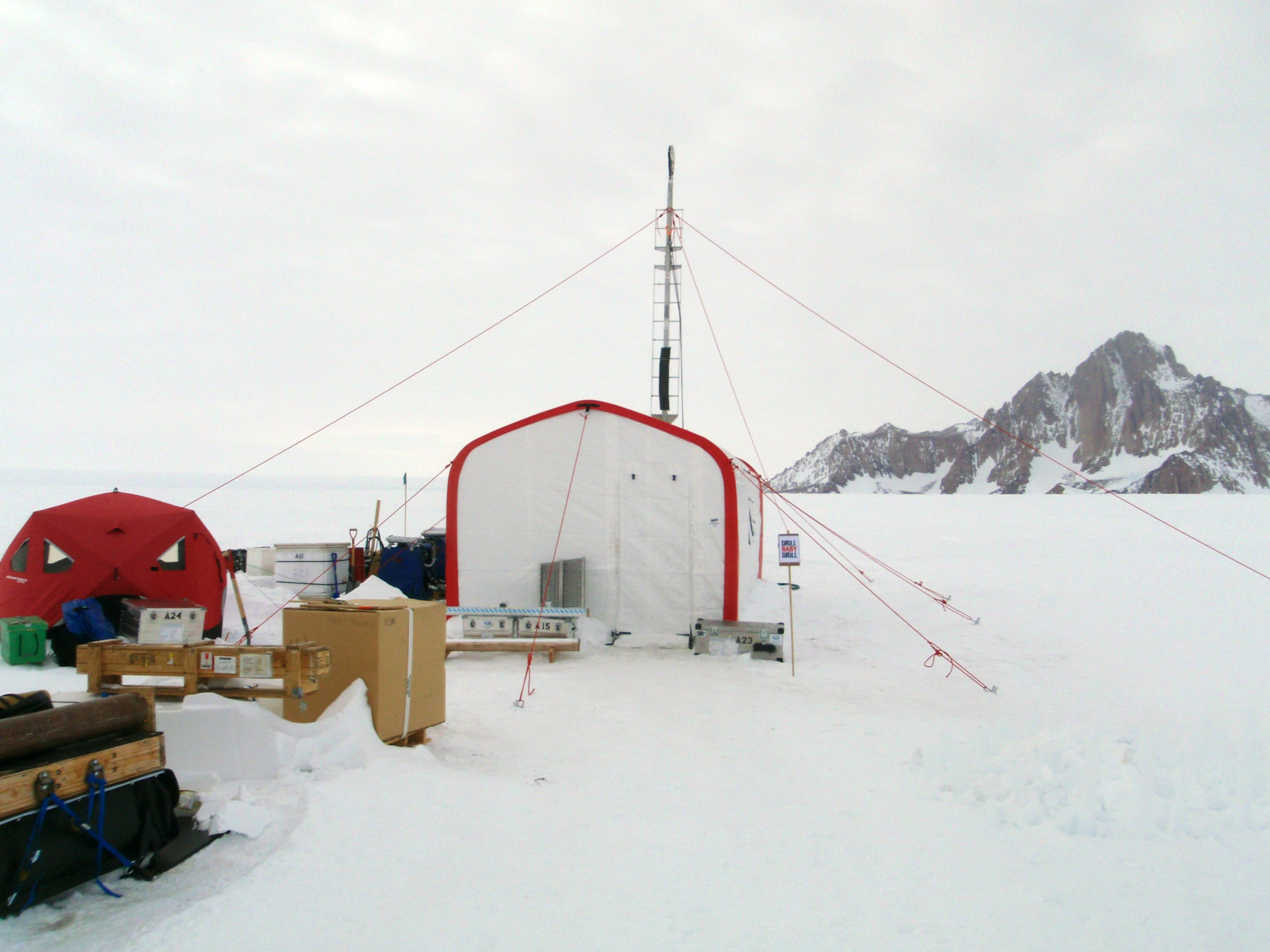

Albert, executive director of the NSF-funded U.S. Ice Drilling Program, said that COVID-19 concerns led most U.S. ice core drilling projects on the Greenland Ice Sheet to cancel their 2020 field seasons. Ice cores provide a window into climate and human history that is invaluable in understanding the current climate change crisis. In March, the Danish-run international East Greenland Ice-core Project (EastGRIP), which studies how ice streams may contribute to future sea-level rise, also cancelled its 2020 season.

“Researchers live in small tents out on the ice. If someone brings COVID-19, everybody is going to have it,” said Albert, who attended the Arctic COVID-19 conference from her home in Vermont.

[An Arctic science expedition changes plans to overcome logistical challenges from COVID-19]

Conference speakers noted that many essential Arctic operations continue to operate during the pandemic. U.S. Coast Guard officials said they were “fully operational” in Alaska for potential search-and-rescue or oil spill responses, with crews mindful of health risks and outfitted with personal protective equipment as needed. They said they still hope to deploy the Coast Guard Cutter Healy, a medium polar icebreaker designed for research, to conduct science missions later in the summer.

Researchers speaking at the conference said they were also exploring alternative technological options for gathering basic field data, including unmanned operations using drones over land and sea. And field season closings present new opportunities for Arctic researchers to build stronger relationships with local partners.

The remote Toolik Field Station in the foothills of the Brooks Range on Alaska’s North Slope is normally a mecca for U.S. and international scientists and students doing Arctic ecological and climate change research. Because of COVID-19 concerns, it’s closed to outside scientists at least through July 1, said Syndonia Bret-Harte, a University of Alaska Fairbanks professor who is the station’s science co-director. If it should reopen this summer, a 14-day quarantine and COVID-19 test would be required for new visitors, she said in an interview.

As a “stop-gap measure,” Bret-Harte said the 12-member Toolik onsite staff has stepped up efforts to collect data and samples or take field measurements for researchers who can’t come themselves. This is particularly crucial for ongoing studies, such as the decades-old Arctic Long-term Ecological Research site. “We cannot do all the work that you would have done, but hopefully we can help you from having the season be a total loss,” an announcement on the Toolik station’s website told researchers.

[Nunavut wildlife surveys are grounded by pandemic precautions]

Other scientists said the COVID-19 crisis is a “wake-up call” to strengthen connections with local Arctic communities, including Indigenous peoples, to partner in “boots on the ground” research projects.

Community involvement is a key part of a new NSF project in the 600-person village of Qaanaaq, Greenland, one of the northernmost towns in the Arctic. Led by Dartmouth’s Albert, the $2.6 million, four-year program will explore options for transitioning from expensive, polluting diesel fuel for electricity to renewables where possible. A two-week visit to Qaanaaq in April was cancelled, and the scheduled fall visit may be cancelled as well.

In the meantime, Albert is keeping in remote touch with the Greenland lead scientist on the project, Lene Kielsen Holm of the Greenland Climate Research Center in Nuuk, as well as community team members in Qaanaaq. Albert had expected to install a small meteorological station in April to measure wind and other local conditions. Rather than waiting, she is shipping the weather station to Qaanaaq for local team members to install and start taking measurements.

“I actually never thought I would see a pandemic during my life, yet here it is,” said Albert. “It is very disappointing not to go to Greenland now, but it hasn’t killed our project. It will just be a delay.”

Video of the“COVID-19 Impacts in the Arctic” conference is available through the U.S. Naval War College’s YouTube channel (Day One and Day Two).

Cristine Russell is a freelance science journalist, a senior fellow at Harvard Kennedy School in the Belfer Center’s Environment and Natural Resources Program and a member of the HKS Arctic Initiative. She tweets from @russellcris.