The dream of an Arctic railway fades as Sami herders signal ‘veto’

Reindeer herders in both Norway and Finland have expressed strong opposition to the plans.

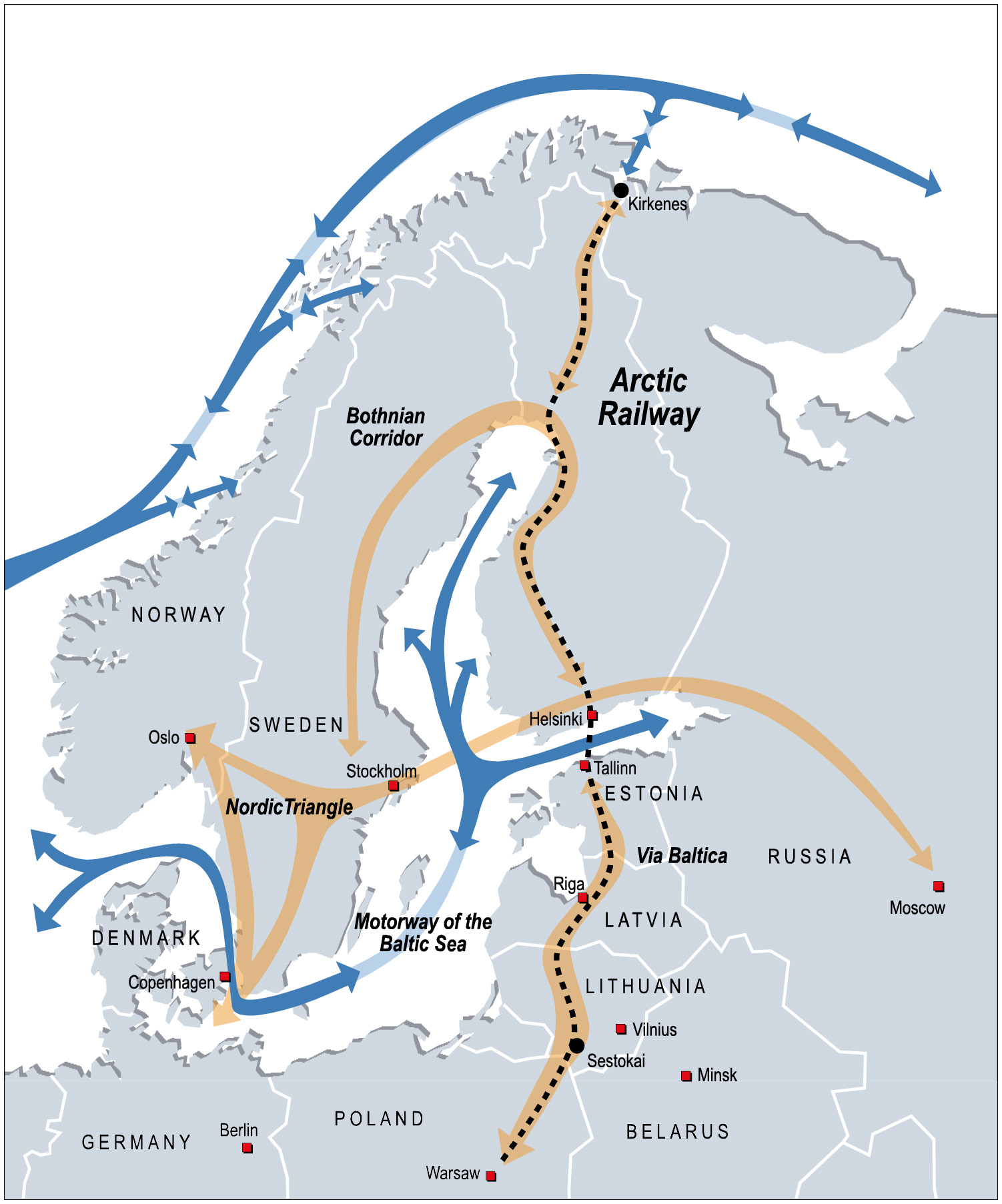

There are few green lights on the track towards a possible new railway supposed to link shipping of cargo from Asia, via the Arctic, to markets in Europe.

Last year, a Finnish-Norwegian working group said cargo volumes are too small to justify the costs, and neither the Finnish nor the Norwegian governments have such a railway between Rovaniemi and Kirkenes on their infrastructure priority lists.

At a debate arranged by the Saami Council in Kirkenes, early February, reindeer herders on both sides of the Nordic countries’ borders said a loud and clear no to the plans.

“Sami voices are often in minority at big Arctic conferences, so we arranged our own debate,” said Christina Henriksen, newly elected President of the Saami Council.

“The negative consequences for the reindeer herders and traditional culture are simply too big to be neglected,” she said.

While municipal authorities in both Kirkenes and Rovaniemi praise the railway idea, the Sami indigenous peoples are the ones that for hundreds of years have utilized the land along the proposed 520-kilometer-long railway corridor.

“The railroad would be a catastrophe for reindeer herding because it will cut our reindeer grazing area in two and it will create a lot of conflicts here,” argued Tuomas Semenoff, from the Väʹččer Reindeer herding district in Sevettijärvi on the Finnish side of the border.

Tiina Sanila-Aikio, former President of the Sami Parliament in Finland made clear that it is no way the Finnish government could approve such railway under the current laws.

“The Constitution of Finland puts an end to the railway,” she said and pointed to Section 17 that assures the Sami’s right to maintain and develop their own culture.

“It is not allowed to undermine Sami culture and our culture is inseparable with reindeer herding, fishing and hunting in the area,” Sanila-Aikio said.

“A railroad will influence swamps, grazing areas, rivers all way between Kirkenes and Rovaniemi.”

A ‘veto’ against the railway by the Sami herders could be the final nail in the coffin for the project. It is unlikely that the governments of Finland and Norway would wish to invite a new conflict with Arctic Indigenous peoples.

In Kirkenes and Lapland, regional politicians have hoped that such a railway would spur economic growth, more infrastructure and create jobs.

Deputy Mayor of Kirkenes, Pål Gabrielsen, supports a new railway, but said during the debate that he is “ready to say no if the consequences are too bad.”

“Listening to the reindeer herders are vital to the process, if there at all will be a process,” he said.

Although governments are not pushing the project forward, Finnish multi-millionaire entrepreneur Peter Vesterbacka, has teamed up with Chinese investors aiming to build an undersea railway tunnel between Helsinki and Tallinn, which — once ongoing track upgrades in the Baltics are complete — would link Finland to mainland Europe. For Vesterbacka, the missing link for a full-fledged cargo flow from the Arctic Ocean to Europe is the extension of the rail tracks from Rovaniemi northbound to the Barents Sea.

Chinese investments for infrastructure in the two Nordic countries, are, to put it mildly, highly political controversial.

Aili Keskitalo, President of the Norwegian Sami Parliament, would like to see an end to the talks about an Arctic railway. Although she agrees with her Finnish colleagues that there are no reason to believe such railway ever will be financial liable, Keskitalo warned that even talks about it is demanding for the next generation of reindeer herders.

“Why should we put resources into an impact study, if it is not financial liable,” she asked rhetorically.

“It is very demanding for reindeer herders. The up-growing generation of herders hear about this and get uncertain about the future,” Keskitalo said and pointed to experiences from other areas in the north of Sweden and Norway where trains kills hundreds of reindeer annually.

“A fence does not solve the problem,” Aili Keskitalo argued.

“Fences are also cutting off natural migration routes. Both at Nordlandsbanen and Trønderbanen [railroads in Norway] we see that hundreds of animals are killed during the winters.”

For Tuomas Semenoff in Sevettijärvi, the railway is simply a question about surviving as a people. “I could still live there, but no longer in the traditional way as reindeer herder,” he said.