The nitty-gritty detail of an icebreaker contract: Analysis

This is a reproduction of an article that first appeared on Sixty Degrees North. If you would like to read more posts by Peter Rybski, you can sign up for his blog here.

On March 7th, the government of Canada awarded a contract to Seaspan to build a polar icebreaker in their Vancouver Shipyards. The following day, there was another big announcement concerning a second polar icebreaker, to be built by Davie.

From a March 8, 2025 Press Release from Davie (bold is mine):

Davie, the Québec-based international shipbuilder, today announced it has been awarded a contract by the Government of Canada for the construction of a needed polar icebreaker. This initiative will leverage Davie’s international presence, with work beginning in 2025, under a robust contract framework that will enable Davie and Canada to set new standards of efficiency and productivity in vessel procurement.

Through this agreement, valued at $3.25 billion [Canadian dollars], Davie will deliver its production-ready heavy icebreaker design called the Polar Max to Canada by 2030. To support the rapid delivery of the ship, Davie will capitalize on the expertise of Helsinki Shipyard, which was acquired by Davie in 2023 with the support of the Québec government. Helsinki Shipyard has built over 50% of all the world’s icebreakers.

The Helsinki Shipyard press release adds a few additional details:

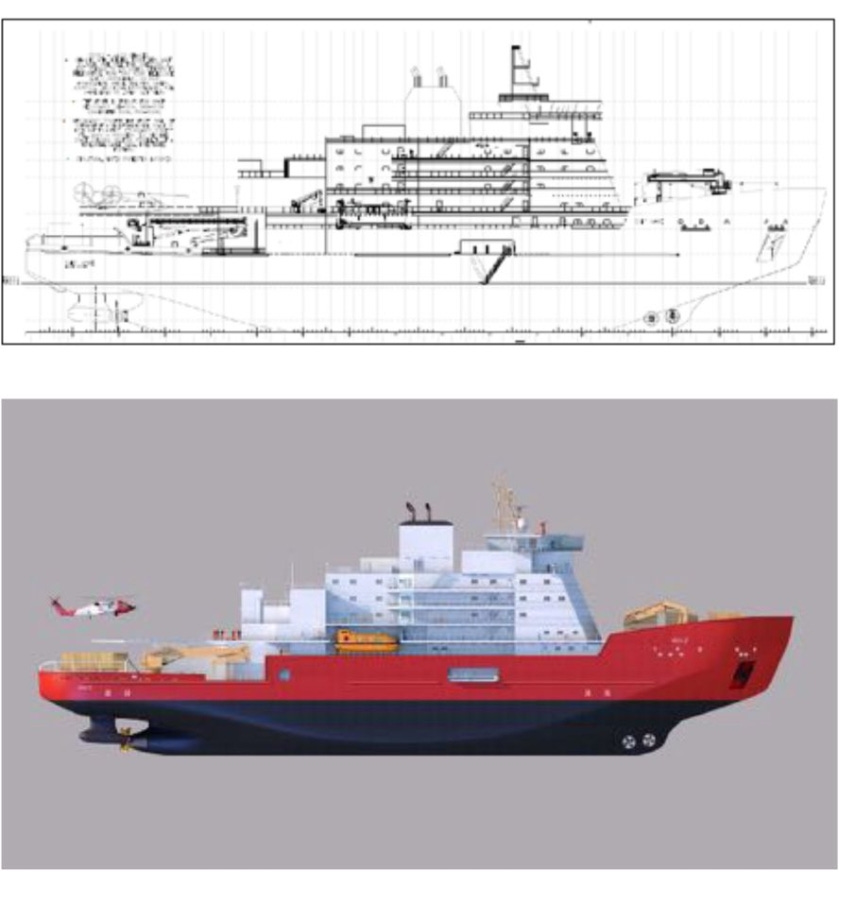

Canadian-owned Davie, which owns the Helsinki Shipyard, signed an agreement with the Canadian government to construct a heavy icebreaker. The new vessel will be based on Davie’s advanced Polar Max icebreaker, created by the Helsinki Shipyard basing on Aker Arctic’s original Aker ARC 148 hull form.

Polar Max is the first newbuild project at the Helsinki Shipyard under Davie’s ownership, and it will be carried out in collaboration between Finnish and Canadian maritime industry experts. The work will begin in Helsinki and be completed at Davie’s shipyard in Canada. The finished vessel is scheduled to be delivered to the Canadian government by 2030. The unique expertise of the Helsinki Shipyard will play a significant role in delivering the vessel on such a fast schedule.

Specs:

Here are some specifications, pieced together from various sources:

- Displacement: 22,800 tonnes

- Length: 138.5 m

- Aker Arctic’s Hybrid DAS propulsion (2 Azipods flanking a fixed shaftline)

- Wartsilä Diesel Engines

This makes Davie’s icebreaker slightly smaller than Seaspan’s. Although the propulsion power of this new design vessel is not known, Helsinki Shipyard’s first design based off of the Aker ARC 148 hull form- a ship contracted for Russia’s Norilsk Nickel, but never built- had a propulsion power output of 30MW. If this holds true for the Canadian Coast Guard design, it would be slightly less than Seaspan’s polar icebreaker (which advertises 34 MW of propulsion power.) I look forward to reading more details about these two vessels.

This Contact is Different

Those of you who don’t follow government shipbuilding might have missed three key points about this contract:

It is fixed price. Canada’s government shipbuilding is known for cost overruns. The other polar icebreaker contract- awarded to Seaspan- is a ‘Cost plus’ contract in which the government will pay all costs plus a margin of profit. In a cost-plus contract, there is less incentive to contain costs. For a fixed price contract, cost savings become profit.

It includes the design. Often, government contracting includes a separate design contract before the build is contracted. For example, Seaspan had a completed, funded design before their build contract was awarded.

It will be partially built in Finland. Government programs normally support only their domestic shipbuilding industry. In this case, in order to accelerate delivery, construction will take place partially in Helsinki Shipyard but will be completed in Davie’s Quebec shipyard.

A Brief History

As I outlined in Saturday’s article about Seaspan’s polar icebreaker contract, Canada’s desire to build a true polar icebreaker goes back to the 1980s. While Seaspan had contractual work associated with the program already in 2011, Davie didn’t enter the picture until about ten years later.

2021:

Canada’s National Shipbuilding Strategy is updated to add a second polar icebreaker for the Canadian Coast Guard, to be built by Davie in Quebec (pending Davie’s certification as the NSS’s third shipyard for large vessel construction). The first vessel will be built at Seaspan’s Vancouver Shipyards.

2022:

October: Finland’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs denies Helsinki Shipyard an export license because of additional sanctions imposed on Russia following the escalation of the war in Ukraine.

2023:

November: Davie completes its purchase of Helsinki Shipyard, which includes some icebreaker designs (including Polaris and the Norilsk Nickel vessel).

2024:

September: The Canadian Government awards Davie its first contract associated with the polar class icebreaker program- $16.47 million (Canadian) for advance work1.

That brings us to the March 2025 announcement. Note the lack of a design contract along the way. I had assumed up until very recently that Davie would be building the same vessel as Seaspan, but starting a bit later as anticipated in the 2024 report by Canada’s Parliamentary Budget Officer.

Leveraging Finland’s Process

On March 5th, I attended Helsinki Shipyard’s 160th anniversary reception. At the event, I heard executives from Davie and Helsinki Shipyard discuss their polar icebreaker design- called the Polar Max. Now we know that this is the same design Davie will build for their Canadian Coast Guard polar icebreaker. I heard multiple times that the design was ‘production ready’ and that Helsinki Shipyard could deliver the vessel in 36 months. While production ready is not a typical term used in shipbuilding, the timeline- 36 months from order to delivery- is typical for Helsinki Shipyard.

For example, the Finnish Icebreaker Polaris was ordered in February 2014 and delivered in September 2016- about 2.5 years.

This will shock my North American shipbuilding friends- but Helsinki Shipyard does basic design, detailed/production design and construction in parallel. This is a standard commercial process for the shipyard, one that I will write more about in the future. This means that the design must be stable at contract award. Not complete, but stable.

As Alex Vicefield, one of Davie’s owners, wrote on LinkedIn (emphasis mine)2:

Our acquisition of Helsinki Shipyard has made this possible. With a legacy of designing and building nearly 60% of the world’s icebreaker fleet, their expertise is unmatched. Unlike the traditional Canadian approach of fully designing before building, Finland’s proven method allows construction to begin while design is still evolving – drastically improving speed and efficiency.

I spoke to some of the shipbuilders at Helsinki Shipyard earlier this week. They highlighted that their process works because their ship design team knows how to complete detailed design in a fashion that allows portions of the ship to be built before the overall design is complete. Of course, this process means that the major decisions must be made early- and the design must be stable. When asked about change orders on LinkedIn, Alex replied:

basic design is done and CCG requirements are defined so main spec won’t change… it’s on us now

This means that the Canadian Coast Guard might not get everything on its Christmas wish list- but it will get everything that it needs as defined in its key requirements.

There are other differences in how Helsinki Shipyard builds ships- such as their quality assurance process. But more on that some other time. The bottom line is that for this to work, you need a trusted shipyard. And Helsinki Shipyard certainly has the history to warrant that trust.

The same folks at Helsinki Shipyard were confident that there will be construction ongoing if I come back to visit in about six months. I can’t wait to do that and report on the progress.

A Canadian Deal- Especially in Price

This is not a full Finnish deal, however. Helsinki Shipyard will be sharing the build with Davie’s Quebec shipyard, including bringing Canadian shipbuilders to Helsinki to learn from their Finnish partners. This will help Davie not only to complete this icebreaker in Quebec, but will add experience that will assist the Quebec yard in building other icebreakers under Canada’s NSS- such as the program icebreakers.

The multiple-yard build means that Davie won’t deliver the ship in 36 months- but a delivery before 2030 is still amazingly fast for a North American program.

It also- glaringly- affects the price of the vessel. I’ve spoken with people at Davie who stressed to me that this is a Canadian deal. And, despite the $3.25 Billion (Canadian) price tag, this may end up saving Canada money.

First, the fixed price-contract with Davie is already cheaper than Seaspan’s effort. Yes, Davie’s contract announced on Saturday, at $3.25 Billion (Canadian), is slightly higher than Seaspan’s $3.15 Billion (Canadian) Cost-plus contract to build their polar icebreaker. However, as the Canadian government backgrounder notes, Seaspan had previously been awarded three contracts for the program with a total value of $1.12 Billion (Canadian), for a total of $4.27 Billion (Canadian).

Cost growth has been a problem for Canadian government shipbuilding. While there is plenty of blame to go around, Seaspan’s recent deliveries have all come in more expensive than estimated. One particularly egregious example is the Offshore Oceanographic Science Vessel (OOSV). Originally scheduled to cost $109 Million (Canadian) and be delivered in 2017, the PC 6 research vessel is now expected to cost $1.28 Billion (Canadian) and will be delivered in 2025.

A report from Canada’s Parliamentary Budget Officer from 2024 estimated the total development and acquisition of two polar icebreakers to cost $8.5 billion (Canadian) and to deliver the ships in 2030-2031 and 2032-2033. The report’s assumption was that Davie would begin construction in 2026-2027 with delivery in 2032-2033.

If Davie manages to deliver the vessel by 2030, this will beat expectations both in cost (approximately $3.4 Billion3 (Canadian) including all contracts, as opposed to the $4.25 Billion (Canadian) anticipated) and timeline, delivering by 2030 as opposed to 2032-2033.

Thoughts and Comments

Congratulations to the teams at both Davie and Seaspan. The West- especially North America- needs more polar icebreakers to meet today’s challenges.

I will be tracking both programs closely, although for practical purposes it will be easier for me to follow the work in Helsinki Shipyard, a short distance from my home.

I wish Seaspan well, but it seems to be following the traditional route for government programs- the route that leads to cost overruns and delays. I suspect that there are lessons to be learned by following and comparing both of these programs.

This Davie/Helsinki deal strongly resembles some proposals for Finnish cooperation in building U.S. Coast Guard icebreakers from my time at the U.S. Embassy in Helsinki, Finland. Their design and build process- which results in faster builds and generally lower costs- differs greatly from the current U.S. procurement process.

The timeline of this deal means that the customer- the Canadian Coast Guard- has had a shorter window for input. Some might see the resulting ship as a compromise solution, as it will not have the traditional years of back-and-forth4. But this might also show the true opportunity cost- in the actual build cost and timeline for vessel acquisition- of the current system.

I will detail this in the future, but want to add that fundamentally, it is not different from what the GAO has been advocating. That is, a stable design before beginning construction. One of the many problems with U.S. Government shipbuilding is, reportedly, the continuous changes requested by the government. Making key decisions early- and sticking with them (or at least understanding the trade-off in cost and build from changes) is something that will be required to take advantage of Finnish capabilities in designing and building icebreakers.

I spent some time this week at both Helsinki Shipyard and Aker Arctic discussing the design and construction of icebreakers and plan on writing more about it in the very near future. If you have specific questions, please send them my way.

All the best,

PGR