The plug keeping the Arctic’s oldest ice in place is getting leaky

The loss of more multi-year ice through the Nares Strait could threaten both the Last Ice Area and Pikialasorsuaq.

As Arctic sea ice declines, a corner of the Arctic Ocean north of Greenland and Canada’s Ellesmere Island has remained a bastion for the region’s oldest, most resilient ice.

This area, measuring hundreds of thousands of square kilometers and now nicknamed the Last Ice Area, holds much of the Arctic’s remaining multi-year ice, which in some cases may be as much as a 10 years old. It could continue to remain covered by ice during the warmest months of the year well into the future — and perhaps provide a refuge for species from algae to polar bears that rely on sea ice for their survival.

Not surprisingly, the area is shrinking as sea and air temperatures rise, the result of global warming. Even so, scientists have remained hopeful the ice here could persist. But those hopes may be dashed by the results of a paper published in the most recent edition of the journal Nature Communications.

[“Last Ice Areas” of the polar North should be world heritage sites: IUCN]

The decline, according to the findings, is as much as double the rate of sea ice being lost in other parts of the Arctic Ocean, due to more ice being drained from the area through the Nares Strait — which runs between Greenland and Ellesmere Island and connecting the Lincoln Sea and Baffin Bay — than previously thought.

Although ice flowing south out of the Arctic is not an unknown phenomenon, ice only drains from the area of the Lincoln Sea that is permanently covered by sea ice for a short period each year. While the amount of ice flowing out of the Arctic along the eastern Greenlandic coast has not changed, there is more ice flowing out of the Nares Strait than in the past.

Because it appeared that drainage was not much of an issue, scientists had previously concerned themselves primarily with ice-loss stemming from melting. And the relatively slow pace at which this occurs had fueled the hope that the ice in this area could serve as a seed for the regeneration of sea ice, in the event that global warming could be reversed.

[Why winter sea ice re-growth in the Arctic has stalled — and what it means for the rest of the world]

The ice that is typically lost through the Nares Strait flows out during the summer. The rest of the year, ice dams, known as ice arches because of their shape, at the northern and southern ends of the strait prevent this from happening.

However, the length of time each year that ice is being held back is remarkably shorter than in the past, according to Kent Moore, a physicist with the University of Toronto Mississauga and the lead author of the paper. And the research suggests that the pace of change is accelerating.

Using satellite images dating back to 1995, the authors of the paper found that while these ice dams previously held back ice for between 200 and 300 days each year, they now only do so for about 150 days annually, amounting to a loss of about a week a year on average.

[Listening tour hears Inuit call for cross-border polynya management]

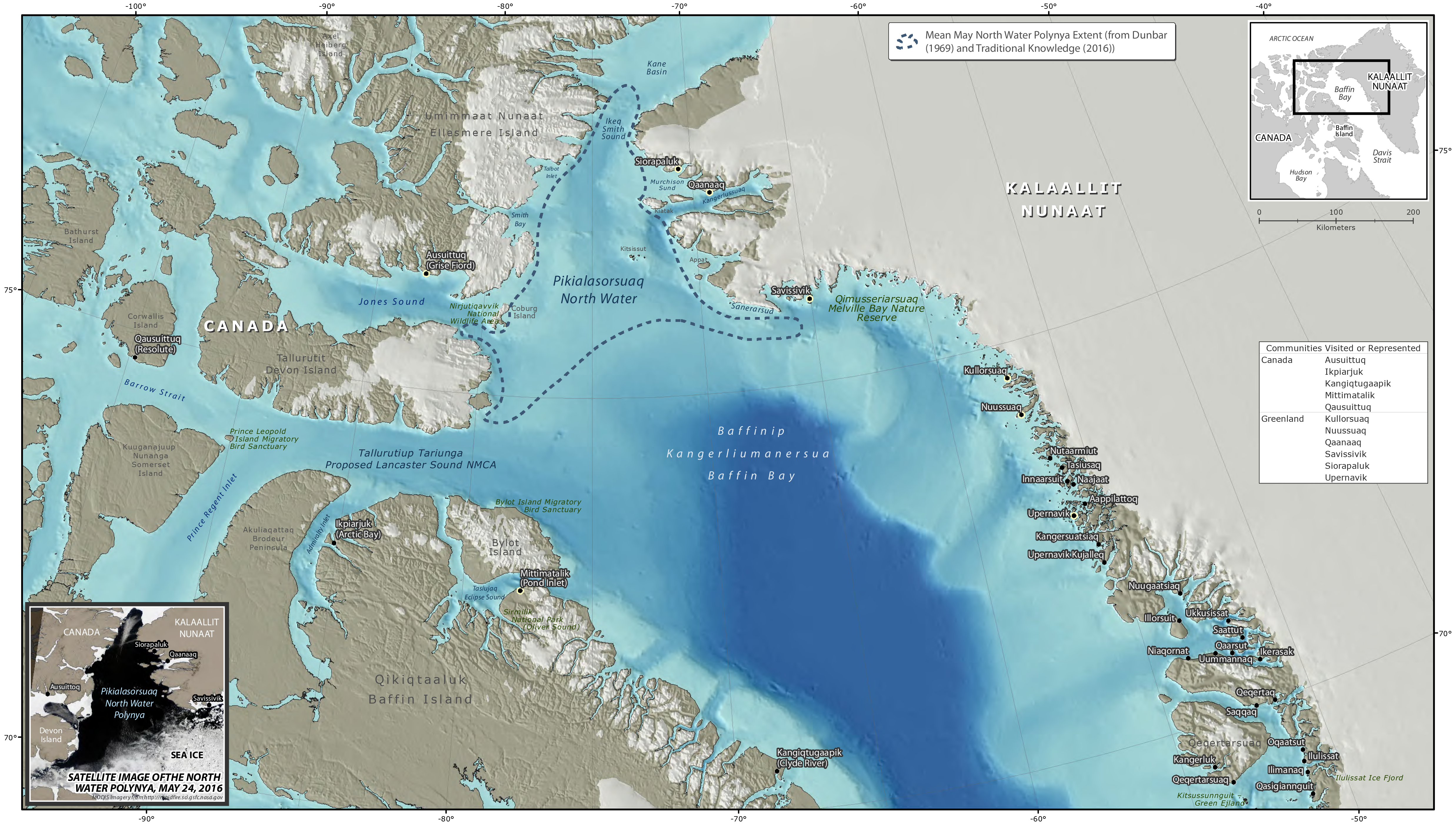

In addition to potentially hastening the destruction of multi-year ice in the Arctic Ocean, the situation may also threaten the formation of Pikialasorsuaq (also known as the North Water Polynya), an 85,000 square kilometer expanse of water extending from the southern end of the Nares Strait to the southern coast of Devon Island (see map below) that remains ice-free year-round, encircled during the winter by frozen ocean.

Pikialasorsuaq is reckoned to be the most biologically productive region of the Arctic Ocean and has supported human habitation for perhaps 5,000 years. Indeed, the ice in the Nares Strait is called an ice bridge and, in addition to supporting animal migration, it has supported several waves of migration of humans from what is today Nunavut into modern-day Greenland. Today, Pikialasorsuaq remains an important source of marine mammals for Inuit subsistence hunters.

The current configuration of Pikialasorsuaq, according to the scientists, depends on the presence of the Nares Strait ice dams to restrict the southward flow of ice. When that happens, winds and ocean currents to that occur in the vicinity of Smith Sound — to the north of Baffin Bay — can prevent ice from forming.

More ice in these waters would likely lead to the failure of Pikialasorsuaq to form and might lead to biological changes that would be noticed throughout the food chain, according to the paper.

Moore theorizes that the reason for the shorter period is that ice has become thinner and less stable. That the process is continuing, the paper concludes, does not bode well.

“The stability of these arches is a function of the thickness of the ice,” the paper stated, “and there is a concern that the thinning of the Arctic ice pack may negatively impact their stability resulting in an acceleration in the loss of multi-year ice from the Arctic as well as impacting the ecosystems of the North Water Polynya and the Last Ice Area.”

Doing anything to reverse the situation directly, according to Moore, is unfeasible.

“The scale is so huge and the region is so remote. The only thing we can do is cool the planet down. Then the arches will hopefully naturally form again.”