The Polar Code is in force now. Will it be enough to protect the environment?

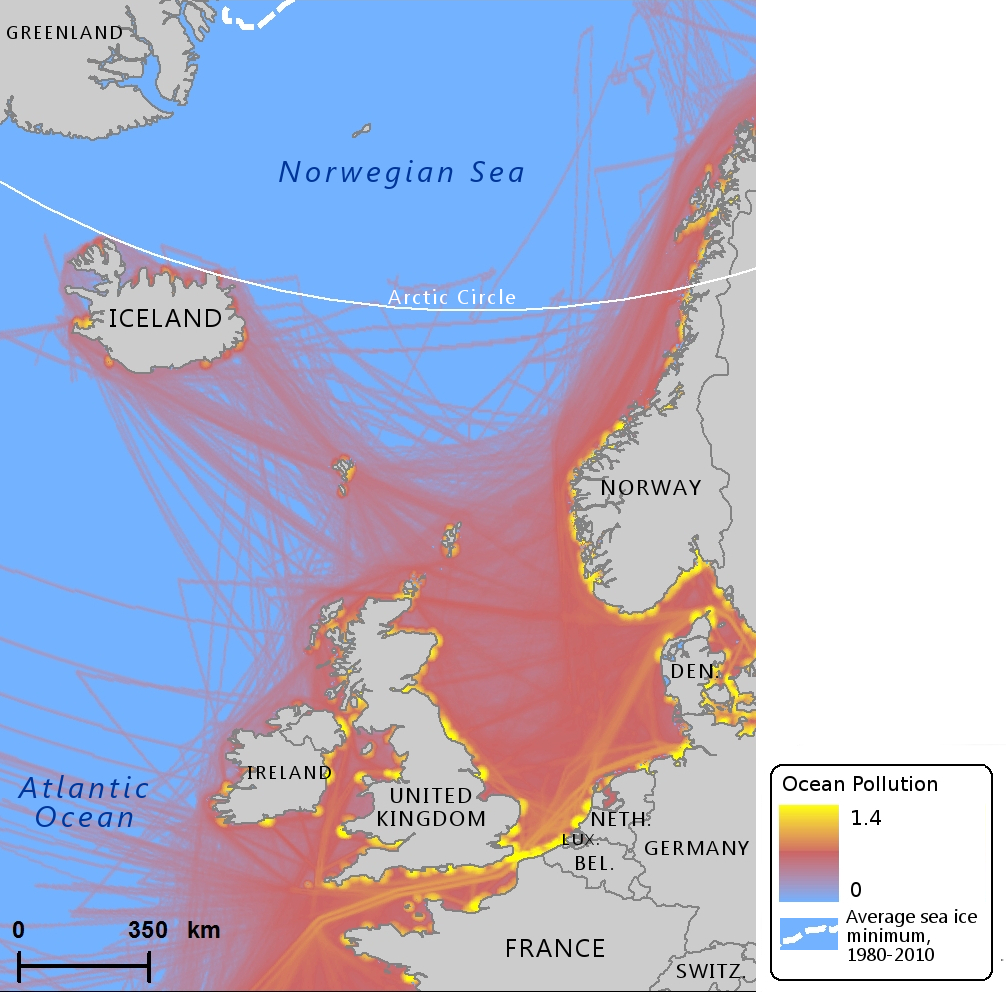

On Jan. 1, the International Maritime Organization’s Polar Code entered into force. The new regulations are intended to improve safety at sea and environmental protection in Arctic and Antarctic waters. Years in the making, the Polar Code couldn’t have come sooner, for the number of vessels, particularly cruise ships, in the Arctic grows each year. Cruises are increasingly venturing into the Arctic in order to cater to tourists seeking destinations marketed as pristine and untouched. And indeed at a regional scale, the world’s northernmost oceans are relatively unpolluted compared to the rest of the world, as the map below reveals.

Yet trading a holiday in the Mediterranean for one in the Arctic comes with consequences for fragile polar ecosystems. In the Arctic, cruise ships are often mentioned in the same breath as “ecotourism,” with tourism seen as an environmentally friendly alternative to industries like oil and gas or mining. Yet cruise ships generate large amounts of pollution. In terms of wastewater generation, cruise ships can also be worse offenders than lightly staffed cargo ships simply by virtue of having so many people on board.

Cruise-related pollution includes black water (sewage), gray water (from sinks, laundries, showers, etc.), and oily bilge water. Cruise ships also spew black carbon into the air, especially when they burn heavy fuel oil (HFO), which organizations like HFO-Free Arctic are trying to ban from the region. When the soot released into the air from burning HFO falls onto ice and snow in the Arctic, it can accelerate melting and, as a consequence, climate change.

[Push is on to get dirty heavy fuel oil out of Arctic shipping]

The boom in Arctic shipping in part thanks to more navigable waters was epitomized, last summer, by the first-ever transit of the Northwest Passage by a major cruise ship.

Though Crystal Serenity’s pioneering voyage attracted major headlines, more modest cruises into the Arctic are arguably exerting a bigger overall impact. Crystal Serenity had some 800 passengers and at least 600 crew. Yet according to John Kaltenstein, a Senior Policy Analyst at Friends of the Earth U.S., 10 other cruise ships with over 1,000 passengers traveled to the Arctic last year. That makes for 10,000 people who sailed through the Arctic in addition to Crystal Serenity’s high-paying customers, all leaving various forms of pollution in their wake.

[Luxury cruise ship sets sail for the Arctic from Seward]

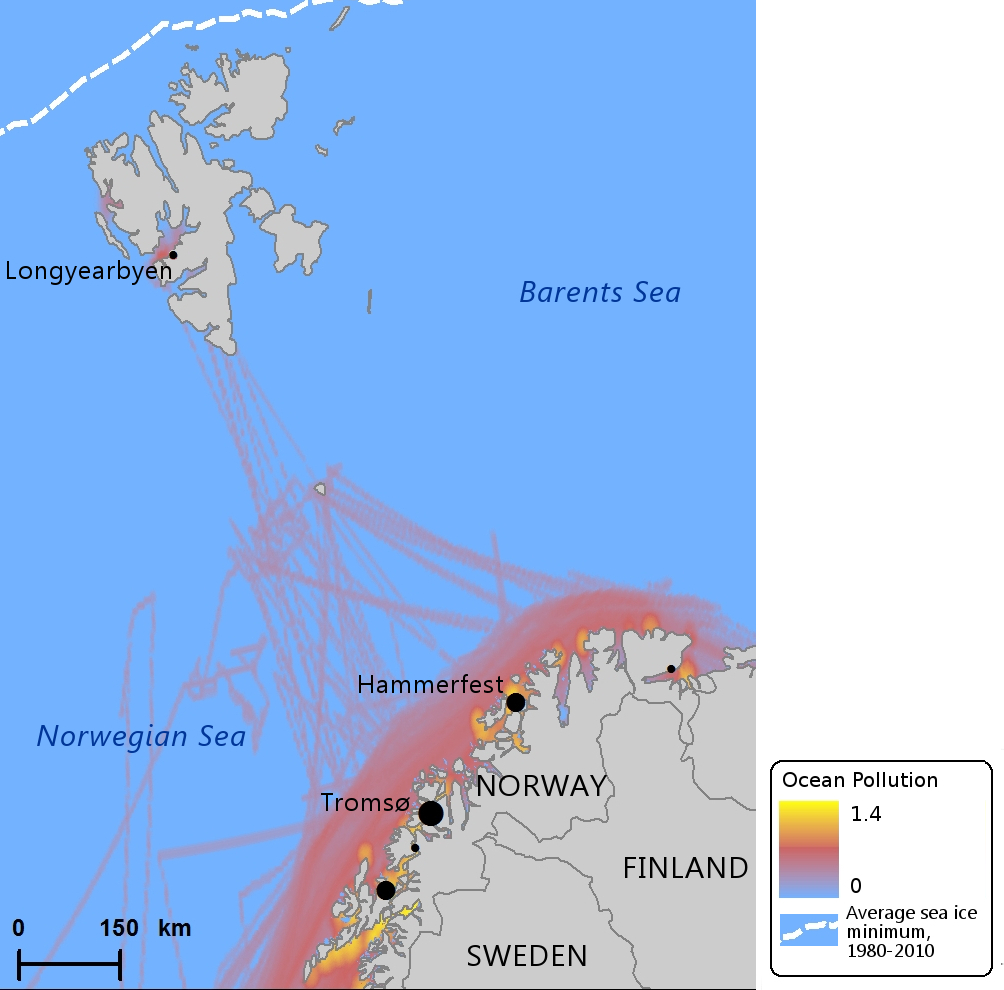

Many of these cruises travel to places like Svalbard and Iceland, where high levels of marine traffic have resulted in elevated ocean pollution. The waters around Iceland, in fact, appear almost indistinguishable from the heavily trafficked waters around the United Kingdom. Though Iceland is imagined as lying on the frigid periphery of Europe, the high levels of pollution around its coastline reveal its deep integration into the North Atlantic shipping network.

Even Greenland, which sees a lot of smaller-scale traffic from personal vessels and cargo ships making deliveries up and down the coast, has relatively polluted waters.

Crystal Serenity voluntarily adhered to stricter environmental controls than required by law, including using marine distillate fuel, a cleaner grade than HFO. But Arctic cruises that are away from the spotlight are not likely to voluntarily follow the same standards set by the high-profile voyage.

That’s where the Polar Code could come in useful. But the policy is not as strong as it could be. The regulations ban heavy fuel oil in Antarctica, but not the Arctic. Attendants at the 10th Arctic Shipping Summit in Montreal this week will discuss whether to expand the ban into the Arctic. The Polar Code also prohibits oily discharge, but it fails to mention of gray water even though it can introduce “faecal coliform bacteria, nutrients, food waste, and medical and dental waste” into the surrounding seas, according to a report associated with the 2013 Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting.

For a story I wrote for this month’s issue of The Maritime Executive on pollution solutions for the global cruise shipping industry, I interviewed John Kaltenstein, senior policy analyst at Friends of the Earth U.S., regarding the environmental impacts of Arctic cruising. He was kind enough to let me republish our wide-ranging conversation in full. We touched on the Polar Code, cruise-related pollution, the fate of the Arctic Ocean under Trump, and what the deliberate pollution cover-up at Princess Cruise Lines means for the Arctic.

MB: How will the new Polar Code affect cruise shipping?

JK: In a nutshell, I don’t think it will affect it that much. There seems to be a tendency or a movement of larger cruise ships into the Arctic. I think our records indicated that there were 11 that had over 1,000 passengers and crew that traveled in Arctic in 2016, and I don’t think that trend will diminish in any way going forward – especially in light of the successful cruise ship activity of the Serenity through the Northwest Passage last summer. So I think the industry is flourishing. From a lot of parts of the world – Asia, Oceania – we’ll see continued activity into the Arctic. I don’t think the Code will constrain that activity.”

MB: Will the Polar Code help reduce pollution?

JK: The environmental groups were fairly critical of the environmental portion of the Polar Code. Heavy fuel oil was a big issue for us. There’s a recommendation there with respect to the Arctic, but we felt more should have been done with respect to a fuel that poses so much risk to the region.

Some of the other provisions in the Code also didn’t improve the situation all that much. When you look at the sewage provisions, we don’t believe they added a lot. There, of course, is no Polar Code provision with respect to gray water, which is a big issue when you’re talking about cruise ships – the amount of wastewater at issue. Those are the areas we felt are deficient and still are. Hopefully, they’ll be addressed at some time going forward. As for now, there are definitely some large gaps when you’re talking about pollution control and some of the environmental provisions in the code. And cruise ships do represent a lot of waste stream. And especially in an area like the fragile Arctic, we believe a lot more can be done. We’ll have to look to other measures besides the Polar Code.

MB: Do you think cruise ships could take it on themselves to try to reduce pollution?

JK: A lot can be done voluntarily. There will probably be some focus on what cruise ship lines are doing in the Arctic. As I mentioned, with the 11 cruise ships with 1,000 passengers or more, more and more lines will be entering into those waters, and I think they should be evaluated because the types of operations can really differ.

The Serenity did a number of positive things including using marine distillate fuel, but many aren’t sure that others will follow suit in terms going above and beyond certain environmental aspects. I think this is a situation where the market and information can make a difference in terms of environmental performance in terms of the industry. Because the Code is not going to provide the stringency we need, and national regulations do vary a good deal. So this is one of those areas where we could see some significant improvement by looking at what actors are doing. If consumers and policymakers need information about practices, those voyages need to be transparent. That would help a lot. Then we can talk about setting high standards and using good practices. There’s been some good stuff in the Arctic Council about best practices, and we’re hoping these can translate into real world benefits and minimizing risks. The environmental community would like to see that, as well as international organizations in the Arctic, policy makers, and the Council.

In the short term, that’s what we’re going to have to look at. We might see some efforts at the national level. And you know, if we’re talking about voluntary measures, the lines can do that immediately this coming season. We’re hopeful and I think the issues in the Arctic are being covered a lot more – somewhat in mainstream press, but definitely in niche and industry press. Sea ice and climate change have definitely been getting some attention in the mainstream press as to how that’s opened up the Arctic for travel and leisure.

MB: What is the number one threat posed by Arctic cruising?

JK: The number one threat is still represented by heavy fuel oil in terms of both spill [possibility] but also the pollution profile in terms of warming and air quality impacts. I think we could do without it. We have been doing without it in some parts of the world for a good chunk of time. For us, it really comes down to the industry showing the will to be an environmentally responsible actor. I think the rhetoric is often there, their professing to be responsible actors, but the will is often lacking. You’re judged on what you do up there, and this is one of those very discrete cases where you’re operating on heavy fuel oil or liquefied natural gas. What are you doing up there to make a difference in terms of your impact or profile? I think we have a good precedent with the Serenity. Hopefully other lines in the region can follow suit. It’s definitely a good start.

There are other issues. Wastewater needs to be taken into account: what kinds of treatment systems, what are they doing with their gray water – it’s a concern for environmental groups and Arctic organizations, especially in the Bering Strait area. There’s lots of concern about what this influx of cruise ship activity, especially large cruise ship activities, will bring in terms of discharges and how it will affect their way of life and subsistence practices. That’s a very real issue and if you’re familiar with the recent executive order with the Northern Bering Sea Climate Resiliency Area, it’s a good indication of how concerned they are because there is specific reference to discharge in the order.

MB: How do you think the Trump administration will impact regulations on pollution in the Arctic?

JK: I’m hopeful there will be a continuation of the good policies that have put forward by the Trudeau and Obama administrations to safeguard the region. We’ll see what transpires. I think they made a very good start, both countries, especially of late, to chart out what course they’d like to see in the Arctic.

MB: Any last thoughts you’d like to add?

JK: The situation with Princess and the criminal charges and the fine1 – that brings up some real issues in terms of compliance monitoring. This is an issue that concerns me a lot with respect to shipping and the cruise industry. If you look at the different regimes, in Alaska, we have a fairly comprehensive regime in place that pertains to their waters that has stringent regulations with respect to sewage and gray water effluent standards that it must meet including permitting, sampling, monitoring, and record-keeping. It’s a whole gamut of things that one looks at. We also have Ocean-Ranger – independent 3rd-party monitors.

And the Princess case is an important one because I think it shows if you peel back the curtain, and you look beyond that, you see that the situation with Princess was largely premised on a whistleblower incident. Had we not had that, those violations could have continued to this day and we would not know about it – and the records go back to 2005 in terms of when the improprieties started at Princess. I think that should give people pause that especially when operating in very remote regions, if there’s not a third party Ocean Ranger or some kind of independent monitor in place, we don’t really know what’s going on at sea. And the practices like these, like we saw with the Princess Caribbean and some of the other Princess ships, and what was also admitted to, and other Carnival family ships, we’re left in the dark. And we don’t have a rigorous enough compliance monitoring system in place for temperate waters, let alone the Arctic. So that gives me a lot of concern.

I think policy makers and others really have to look at this seriously and the industry itself. Obviously they’re going to be under this court-ordered environmental compliance plan, but there’s also Royal Caribbean, Norwegian Cruise Lines, etc. – they weren’t part of this settlement. So I think we really have to look seriously and evaluate our compliance schemes, especially in the Arctic. And I haven’t been given any reassurance that we’ll be in good hands when we’re operating more in the Arctic, and that’s a very real concern. That for me would be up there with actual pollution source. It’s one of the biggest deficiencies that I see right now. Because obviously the Coast Guard is doing the best they can with limited resources, but they’re not out there on the ships with every line, every cruise ship, in the engine room, etc.

And you know, practices like these that we saw with the Princess incident could foreseeably occur in the Arctic and we would not know. We wouldn’t have the ability to stop those. That’s a problem. I think Friends of the Earth are going be looking more at what can be done in terms of these regimes to see what we can do to make sure the environment is being protected. I think looking at Alaska and maybe elsewhere to see what has worked to see that the standards will be complied with is a very important way to go.

Mia Bennett is Ph.D. candidate in the UCLA Department of Geography and writes the Arctic policy blog Cryopolitics, where this piece first appeared.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly quoted John Kaltenstein as saying that “national regulations do carry a good deal.” In fact, he said that such regulations “vary” a good deal. This story has been updated to correct the error.