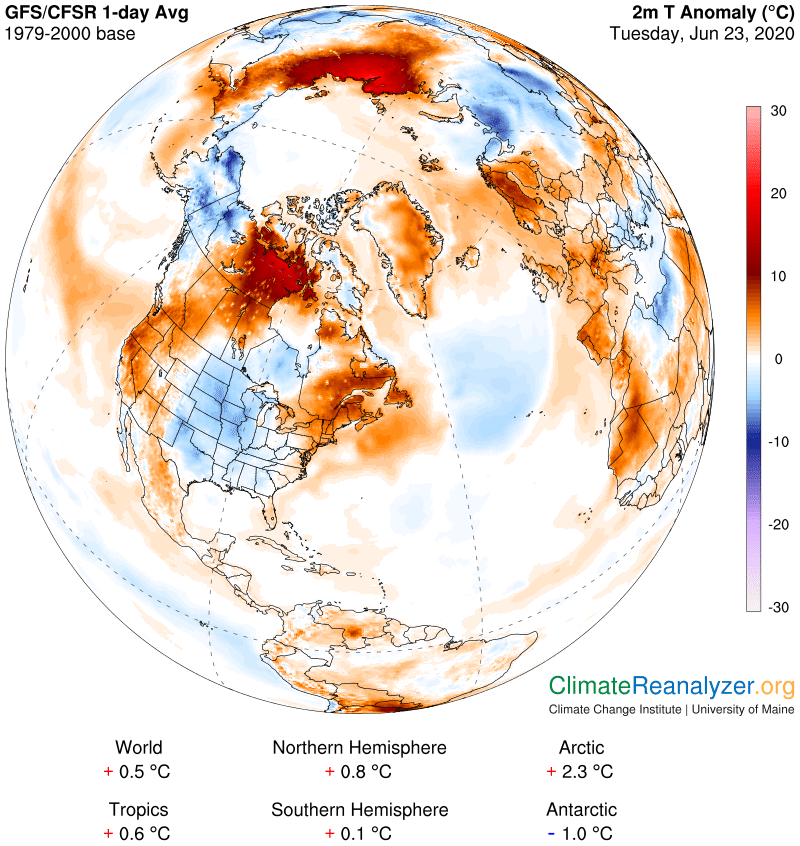

The Russian Arctic is seeing record-breaking heat, and an early start to wildfires

“It's just reinforcing this same pattern that we've been in now for months, with these far-above-normal temperatures in Western Siberia.”

Temperatures in the Siberian town of Verkhoyansk soared to 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit on Saturday.

If the temperature reading is verified, it will be the highest temperature ever recorded above the Arctic Circle.

While the 100-degree heat may set a new record, it is not an anomaly. The Russian Arctic has had an unusually warm winter, with the warmest May on record. This was the warmest winter Russia has seen in 130 years.

[WMO seeks to verify ‘worrying’ reports of Arctic heat record]

Verkhoyansk, a town of about 1,300 people, holds the record for the widest temperature ranges on the planet.

The previous highest temperature at Verkhoyansk was 99.1 degrees Fahrenheit in July 1988, but the town has seen 95 degrees or higher at least a dozen times, Rick Thoman, a climate specialist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, told ArcticToday.

“It’s just reinforcing this same pattern that we’ve been in now for months, with these far-above-normal temperatures in Western Siberia,” Thoman said.

Models predict the heat may soon spread to Scandinavia, Canada and beyond.

Last year, Arctic Alaska, parts of Canada and Greenland all saw record-breaking heat. While they are not currently seeing such drastic high temperatures as Siberia, temperatures there are still higher than normal, Thoman said.

https://twitter.com/AlaskaWx/status/1275178592972857345

This points to a general pattern of warming in the North, Thoman said.

“Any individual place, the weather varies year to year,” he said. But every year, at least part of the region sees unusual warming patterns. “Even though it isn’t always in the same place, this warming is so impactful.”

The Russian Arctic has also had an early start to its wildfire season. Some record-breaking wildfires from last year were never fully extinguished, but instead may have smoldered in peat as “zombie fires” that periodically erupted and spread up to a month earlier than usual.

Temperature surges in the Arctic often lead to an influx of fires, for several reasons.

“The land, the forest, the undergrowth starts to dry out sooner,” Thoman said. Plants, shrubbery and trees scorched by high temperatures can become kindling in a fire.

And because of the warmer winter in the Russian Arctic, the snow melted earlier, which means the soil is also more dried-out. Crucially, soil that doesn’t retain moisture doesn’t block fires as well.

The #ArcticHeatwave is ravaging #Siberia with many active #wildfires. Here there are small and large ones in an area just 30km wide(69N) captured today by @CopernicusEU #Sentinel2 #Russia #Arctic #opendata @ESA_EO @defis_eu @stracma @TerliWetter @WMO @queenofpeat @MichaelMannEU pic.twitter.com/1rXdyYuQ8Q

— antonio vecoli 🛰️🇪🇺#️⃣ (@tonyveco) June 20, 2020

Fire severity is also linked to permafrost thaw in Arctic and sub-Arctic boreal forests, in a positive feedback loop. As fires burn away insulating moss on the forest floor, they make permafrost more susceptible to thaw. And as permafrost thaws, drier soils enable more severe fires to burn.

Although much of the wildfire zone in Alaska seems to be at lower risk this season, the southwest part of the state is seeing several large fires. At least one burned about 20 miles from the Bering Sea, Thoman said.

“There’s no record of a large wildfire that close to the Bering Sea, in that part of Alaska, before this,” he said. “And that comports exactly with what elders have been saying for decades: in that part of Alaska, the tundra has been drying out.”

Air pollution from fires will likely double in Alaska in the next 30 years, and that will have significant effects on health, including but not limited to respiratory illnesses.

For Russia, which has also been hard-hit by the coronavirus pandemic, smoke from wildfires could have wide-ranging health effects this year.

It’s “one more complication in an already terribly complicated world,” Thoman said.