“The trust is gone” – tensions on the rise in Norway after more restrictions for Russian fishing vessels

“This is the steering wheel and this is where you control the speed.” Alexey Reginya, the captain of the Russian fishing vessel “Yantarny” shows me the ship’s bridge. This huge vessel, built in the 1980s, rises high in the harbour of the arctic Norwegian town Kirkenes, surrounded by fjords and cliffs.

We are around 8 km from the Russian border.

I’m here on board together with the Kirkenes police, who are conducting a routine check of documents during the ship’s crew change.

“We don’t have all that stuff that Norwegians think we have”, the captain tells me with a smile. He hints to the recent investigations in the media about possible “spy equipment” found on Russian fishing vessels.

“How can you use a fishing vessel for spying? – captain Reginya continues, – Kirkenes is right near Murmansk. There are so many Russians living in Kirkenes. Those who live in Kirkenes could potentially be used for something like this. Whats the point of using seamen for this? I personally haven’t got any orders to spy on something.”

The “Yantarny’s” fishmaster Vladimir tells me that the accusations towards Russian vessels for spying are “absurd”:

“These are private fishing boats and they do not belong to the state in any way. We are just fishing here. All that we watch for here are the shoals of fish”.

“Yantarny” will be docked in Kirkenes until mid June waiting for the mackerel fishing season to begin. Then, as the captain explains, the ship will sail further into the North Atlantic.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Norway remains the only country in Europe, besides the Faroe Islands, that allows Russian fishing vessels to dock.

But tensions are rising. It feels like the door for the Russian fishing fleet is closing.

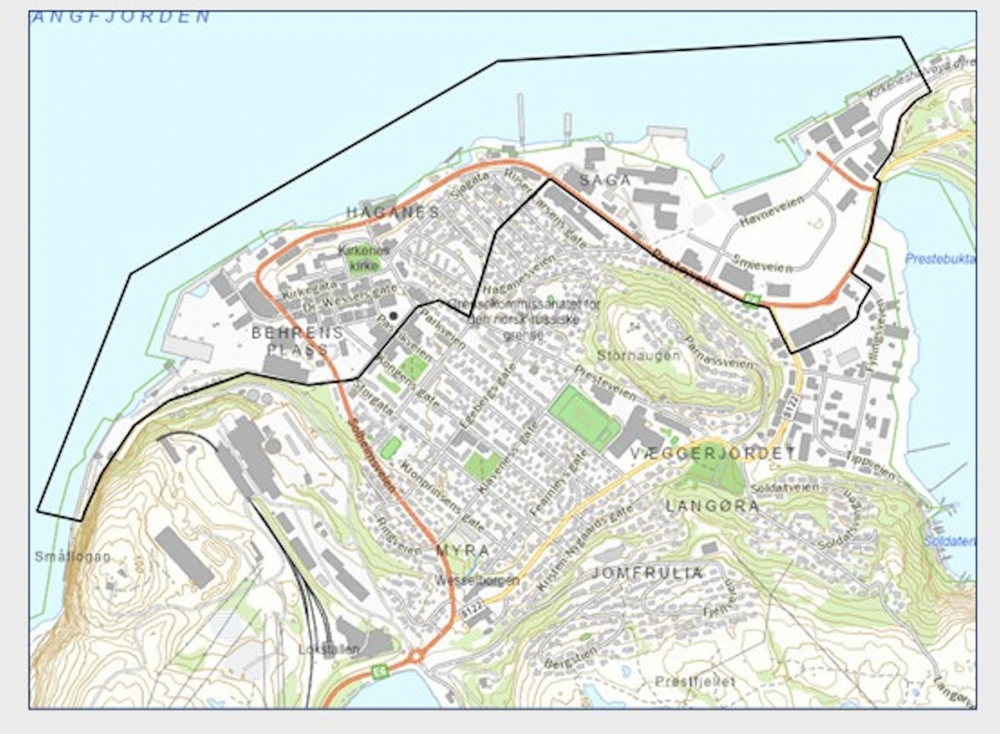

In Kirkenes, local police have recently increased restrictions on the areas accessible to Russian fishermen. The same limitations apply in the nearby harbour town of Båtsfjord.

“Today’s security policy situation in Europe increases the need for security and control activities carried out by the Norwegian authorities. Narrowing the land area is also a measure in this context,” a Finnmark police statement says.

Tensions boil in Kirkenes

I approach a crowd that gathered next to the red brick building of KIMEK – the only shipyard in Kirkenes. Many people here are wearing orange workwear with the KIMEK logo on it.

“Where shall we go if KIMEK doesn’t exist anymore?” Heidi, a local resident, tells me at the gathering. Her husband Ørjan has been working at KIMEK for many years and now they are afraid he could become unemployed.

The Norwegian government has forbidden Russian ships to be repaired in Norway. For a company such as KIMEK, where 70% of its workload comes from Russian vessels, this is a major problem.

“Every war is terrible. Nobody wins a war. It’s only losers”, KIMEK CEO Greger Mannsverk tells me after he finished his public speech at the microphone. “But when the war in Ukraine is over, we are still neighbours with Russia. It isn’t the Russian people that are responsible for the war in Ukraine. It is the mad man in the Kremlin. ”

“I’m here to show the government that we are against closing the harbours for Russian vessels. That would ruin our operations here”, KIMEK employee Tor tells me as the crowd slowly disperses.

The mayor of Kirkenes, Lena Bergeng, stresses the importance of KIMEK’s business for Kirkenes. She shows me her chains of office that are hanging in a glass cabinet on her wall. The golden chains depict the three flags of the neighbouring countries – Norway, Finland and Russia.

“We still have businesses in Kirkenes that depend on Russia”, the mayor tells me. “I think it’s important for the municipality that Russian fishing vessels can still dock here”.

“We should close all the ports to Russian vessels”

But for the municipal council member Brede Sæther the relations with Russia look as grim as the Kirkenes sky on the day I meet him.

As we walk alongside the harbour in May, the cold wind and snow hits our faces.

“We should close all the ports to Russian vessels in order to stop money going into Russia”, Brede tells me as we approach a Russian fishing vessel.

“Rashkov.” Brede reads its name out from the ship’s side. As well as speaking Russian, it is hard to find anyone in Kirkenes who has contributed more to Russian-Norwegian cross-border cooperation than Brede. He has been travelling to Russia for over 30 years as a businessman, including Murmansk, Arkhangelsk and Moscow.

But since the beginning of the war, his opinion about friendship with Russia has drastically changed.

“Russian people have a big responsibility for what is happening. It’s not Putin killing people in Ukraine. It’s Russians. It’s the Russian people taking part in this war”.

“But many Russians are against…”, I tell him.

“Yes of course we should support Russians who stand up against the regime”, he answers, “These are our friends. These are the people that we have to support”.

Brede remembers how he visited Moscow in 1992.

“There was nothing in the shops. There were no restaurants. It was grey. But people were free, things were opening up. It was interesting to come to Russia back then. People were open, wanted contact, they were interested in the West. But now it has all changed”.

But how would Kirkenes cope, when its economy depends so much on the fishing industry?

“The government should help local society here”, Brede tells me.

A visit from Oslo

As the situation around the future of KIMEK began to boil, the Minister of Trade and Industry, Jan Christian Vestre, rushed to Kirkenes from Oslo to talk with worried KIMEK workers.

“It’s a terrible situation, of course”, the Minister Vestre tells me, standing in the main square of Kirkenes, where street signs are duplicated in Russian. “We’ve lived peacefully with our friends on the other side of the border for more than one thousand years. But right now we don’t see the end to the war, unfortunately. We don’t know when we will come back to normal times again. We can’t and we will not let Russia win this war. We are 100% committed about the sanctions”.

Right after the meeting, the minister promised to find a solution back in Oslo.

Meanwhile at the “Yantarny” ship, the passport check conducted by the police is coming to an end.

“It has become much more difficult for us to work now due to the political situation”, the fishmaster of “Yantary”, Vladimir, tells me. “I don’t understand all these sanctions. They only impact simple workers”.

But despite it all, Vladimir still tells me that he supports his president and insists that what’s happening in Ukraine is not a war, but a “special military operation”. But now in Russia a criminal case could be opened against anyone for using the word “war” and for criticising authorities or the Russian army. Thats why interviewing Russians nowadays sometimes feels like a puzzle to me – you never know why people insist on saying one thing or another, what do they really think.

Captain Reginya, rather, keeps his distance from politics:

“The fishing fleet has no responsibility for political issues. We do not take part in it. We’ve always been working here (in Norway) without any problems. We hope to continue that”, he tells me.

A ship stuck in Tromsø

I travel west across Finnmark to Tromsø – the arctic capital of Norway. As the midnight sun shines above the mountains, I walk through the city centre, where I see a monument of an arctic hunter harpooning a whale.

This artwork highlights how the fishing industry has traditionally been one of the main pillars the city stands on.

I meet Daniel Nyhagen – the owner of the “Tromsø Mekaniske” shipyard. He explains to me that many Russian fishing vessels in the arctic were built in Norway. They therefore often need to be repaired by Norwegian mechanics. But now they can’t do it anymore following Norwegian government sanctions imposed after the Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

One Russian vessel in his shipyard has been caught out by the sanctions.

“The ship almost lost all power at sea on the main engine. When they came here, we started dismantling the main engine”, Daniel tells me. “If there had been a better communication between authorities and our industry, we, of course, wouldn’t have started dismantling the main engine. From the 12th of May we now know we are not allowed to do it. So we had to stop in the middle of the maintenance of the main engine”.

Now the ship is stuck in Tromsø. Despite it all, Daniel treats the government’s decision with respect:

“Of course I understand that the sanctions were imposed due to the war Russia is keeping up. And of course we have to respect the rules and the sanctions”.

Uncertainty remains

Here in the High North it’s increasingly visible how the impact of the war in Ukraine is being felt far away from the battlefield. The feeling I got talking to both Russians and Norwegians is that the future is obviously uncertain. But the majority Ive spoken with are certain in one thing – they want the war to end as soon as possible.

Located in Kirkenes, Norway, just a few kilometres from the borders to Russia and Finland, the Barents Observer is dedicated to cross-border journalism in Scandinavia, Russia and the wider Arctic.

As a non-profit stock company that is fully owned by its reporters, its editorial decisions are free of regional, national or private-sector influence. It has been a partner to ABJ and its predecessors since 2016.

You can read the original here.