The Week Ahead: Clearing the air

Stopping Russian sulfur dioxide pollution from a notorious nickel smelter may take economic arguments.

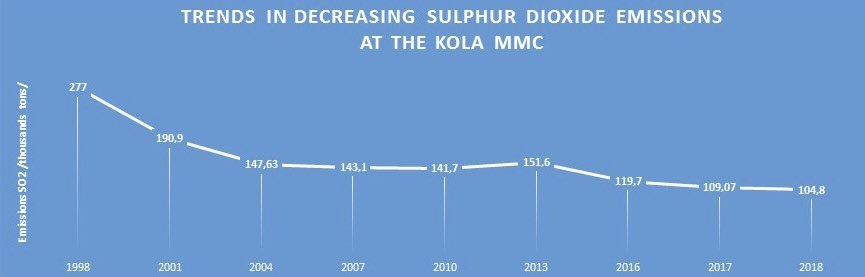

The good news first: Between 2001 and 2018, a Russian smelting operation on the Kola peninsula owned by Nornickel reduced emissions of sulfur dioxide, a toxic gas that causes acid rain, by almost half, according to company data. This without any reported productivity losses. The company has promised a further 25 percent reduction by 2023.

It is hard to put a price on environmental protection, but the cost of the emissions reduction hints at how seriously Nornickel now takes the problem; it expects to spend $17 billion on the effort.

That will go a long way towards improving air quality for those living in the city of Nikel, a city of 12,000 that takes its name from the metal that is the smelter’s main product.

The bad news is that the plant has been contaminating the environment for 80 years, rendering the area to the south, where most of the emissions it belches out wind up, a wasteland. Those who live in the city are less affected, but wind shifts can cause pollution levels to rise as high as 10 times above what is considered safe. In the short-term, inhaling sulfur dioxide makes breathing difficult, while prolonged exposure of the sort the people of Nikel experience is related to lung illness and premature death.

Occasional shifts in the wind that bring clouds from Nornickel over the Norwegian border, resulting in what have been labelled locally as “death clouds,” are accompanied by alerts that warn residents to remain indoors until the coast is clear. The name first began to be used almost three decades ago and helped to make Norwegians aware of the issue, but it was not until last year that Nornickel announced its final push to bring down emissions as low as possible.

Why the change? Some of this may be due to a Norwegian strategy of constant dialogue. Since 1992, the Norwegian-Russian environmental protection commission (which replaced a similar forum that existed during the Soviet era) has met scores of times. During the next such meeting, on Tuesday, Ola Elvestuen, the Norwegian environment minister, has pledged to take his Russian counterpart, Dmitry Kobylkin, to task for a January 25 cloud that floated over Finnmark.

More of a catalyst is likely the economic incentives for doing so. Failing to cut emissions will result in Moscow issuing a crippling fine. So, instead of releasing it the sulfur dioxide it the smelting process produces, Norilsk will run it through a facility that will combine it with limestone to make gypsum, used in sheetrock and fertilizers. Such products could be sold, but there is no shortage of the material, so, for now, it will either be stockpiled or discarded.

[Russia’s most polluted city eyes a clearer sky]

Equally motivational may be a growing movement amongst carmakers to shun irresponsible producers when sourcing nickel for the batteries that power their electric cars. More recently, local officials in Norway have called for a public shaming of producers of other battery-powered devices, such as smartphones.

Elvestuen, in advance of this week’s meeting, made it clear that Oslo would keep pressure on Moscow until the air quality around Nornickel was acceptable. Speaking frankly will win him points at home, but in the end it may be the weight of several big industries that prompts Nornickel to clear the air.

When: Feb 19

Where: Moscow, Russia

Related article

Arctic nickel — not Arctic oil — could soon power the world’s cars

Beginning of the end for HFO

Also this week, in London, work sorting out the details of a ban on heavy fuel oil in the Arctic gets under way.

In October, the MEPC, the International Maritime Organisation committee working with environmental issues, agreed that a ban on heavy fuel oil should be implemented, as it already has been in the Antarctic, and in select parts of the North. The next step, to begin this week, will be for a sub-committee to identify what the impacts of a ban might be, and how they might be addressed.

Depending on how fast it works, the Sub-committee on Pollution Prevention and Response could have something to hand over at the end of the current week-long annual session, thought delegates suggest it will take at least two, in part due to foot dragging by countries who fear a conversion will cost them financially, or their governments electorally. Either way, the earliest such a measure can be adopted is 2020, due to the IMO’s rules of procedure.

[A potential Arctic ban on heavy fuel oil gains momentum]

Heavy fuel oil, say those working to eliminate it, poses two different threats in the Arctic. First, when it burns, it releases black carbon, or soot. In addition to being a health hazard, if the soot settles on snow or ice, it makes it less reflective, speeding the rate at which it melts.

Another concern is the damage that an oil spill would do. Even in temperate climates heavy fuel oil is difficult to clean. As its name suggests, it is a viscous fluid that is difficult to remove from objects it comes into contact with. In the water, it breaks down slowly. The cold air and water temperatures in the Arctic would, say conservationists, make a clean-up impossible.

Shippers have already said they can see the value of changing to cleaner fuels, but, given their higher costs, they are hesitant about burdening themselves unless others do the same. When it comes to heavy fuel oil, the motto is all for none, but none before all.

When: Feb 18-22

Where: London, UK

WWW: Sub-Committee on Pollution Prevention and Response

Related article

Dirtiest shipping fuel to be banned from Arctic

No pebble unturned

On Feb. 22, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, a federal agency responsible for America’s waterways, releases its draft environmental impact assessment of the proposed Pebble Mine, in southern Alaska.

The draft is compiled of input received from the public during a three-month public-hearing process that began on April 1, 2018. The impact assessment looks at the effect the mine will have and seek to propose alternatives.

After the draft EIS is released, the public will have 90 days to submit comments. During that time, the Army Corps of Engineers expects to hold further meetings for public comment.

For more information about the Pebble project, please see: A drop in the bay, in last week’s Week Ahead.

When: Feb 22

WWW: Pebble Project EIS

Related article

Army Corps of Engineers: Pebble Mine EIS delayed, but not by federal shutdown

The Week Ahead is a preview of some of the events related to the region that will be in the news in the coming week. If you have a topic you think ought to be profiled in a coming week, please email ne**@ar*********.com.