Time will tell if this is a record summer for Greenland ice melt, but the pattern over the past 20 years is clear

The Greenland summer melt season is starting earlier, lasting longer, and becoming more intense.

Greenland has been in the news a bit lately. From sled dogs seemingly walking on water, to temperatures soaring to 20℃ above average for the time of year, to predictions of the vast ice sheet being lost entirely, what is going on?

At its most simple: Ice melts when it gets too warm.

Of course, some ice melts every time summer rolls around, but the amount of Arctic ice that melts each summer is growing, and we’re waiting to see whether this turns out to be a record-breaking year for Greenland ice melt.

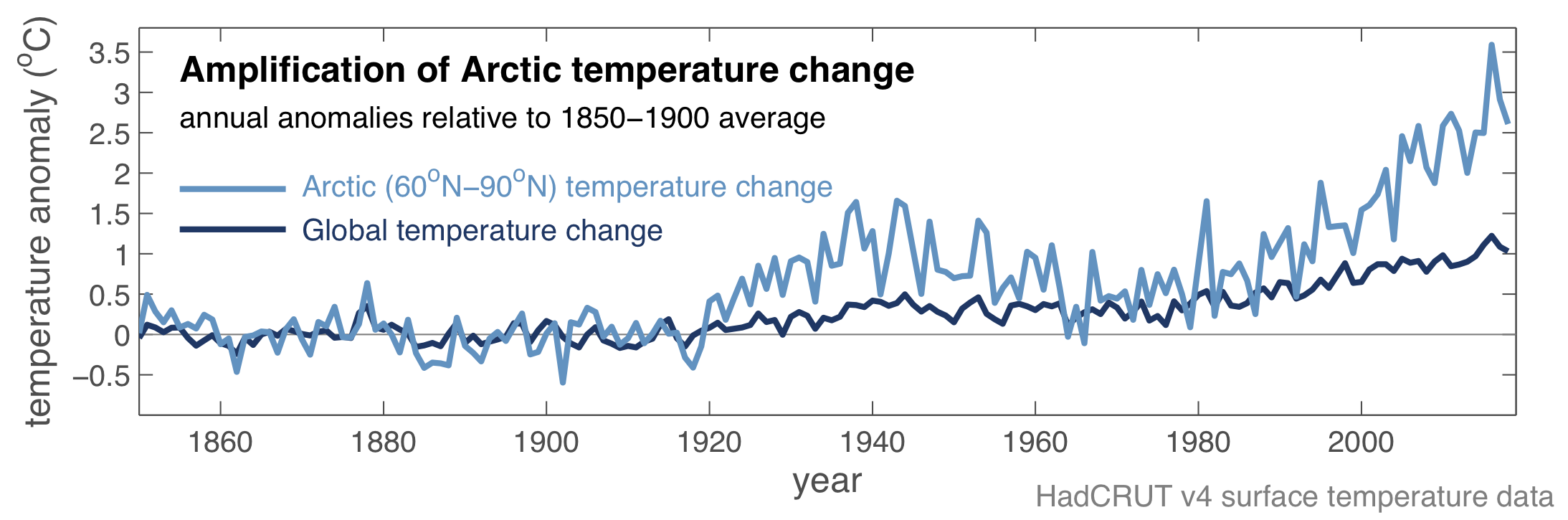

No part of the planet is free from the impacts of human-caused climate change. But Greenland, and the Arctic more generally, is experiencing the impacts particularly severely. Temperatures in the planet’s extreme north are rising twice as fast as the global average.

Greenland is warming so rapidly because of what climate scientists refer to as a “positive feedback.” Despite the name, these are not good. A better term might be “climate change amplifier.”

The Arctic has many “positive feedbacks” or “amplifiers” that worsen the effects of climate change here. For example, as snow and ice begin to melt, the surface darkens, allowing it to absorb more heat and thus melt even more.

This effect is most dramatic when snow and ice are lost completely, as in the case of the dramatic loss of the sea ice covering the Arctic ocean. Arctic sea ice loss is one of the major factors that explains why the Arctic is warming so much faster than the rest of the planet.

Another worrisome characteristic of climate change in the Arctic is the potential for ice melt to accelerate. The temperature threshold at which ice begins to melt means that once the climate has warmed enough to start melting ice, any further warming will rapidly cause an even larger amount of melting to occur. That is the reality beginning to play out in Greenland.

Beginning of the 2019 summer melt season

Last month, ice melt across the surface of Greenland made headlines. Surface melting spiked rapidly and was unusually strong for June. Melting was most intense around the edges of the Greenland ice sheet, and about 40 percent of the entire ice sheet surface was affected to some extent.

Greenland ice melt is typically very irregular during each summer, spiking as weather systems bring warm air masses over the ice sheet. Given this variability, it is not yet clear whether 2019 is going to be an unusually bad year for melting over Greenland — and whether it will rival the worst year on record, 2012, when the entire surface of the ice sheet experienced melting.

But what is very clear from observations since the 1970s (and completely consistent with simple physics) is that as the Arctic climate warms, the Greenland summer melt season is starting earlier, lasting longer, and becoming more intense.

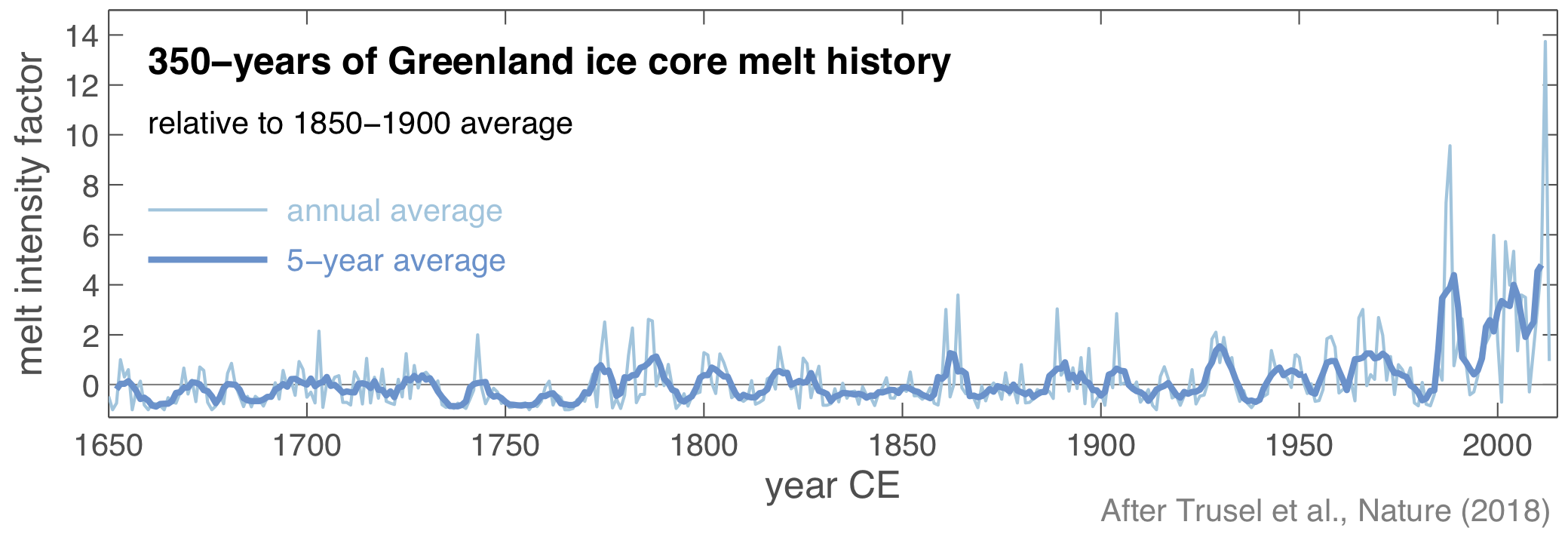

Samples of older ice from inside Greenland’s ice sheet paint an even clearer picture of the changes that climate warming is causing. The amount of summer melting first began to increase in the mid-1800s, not long after human-driven climate warming began. Summer melt over the past two decades has reached levels roughly 50 percent higher than before the Industrial Revolution, and the speed of ice loss from the Greenland sheet has increased nearly sixfold since the 1980s.

Choices for the future

An ice sheet has existed on Greenland for millions of years. But the geological timescales of ice sheet growth and renewal are vastly outpaced by the human-caused changes we see today.

A study published in June this year, at the same time surface melting of the ice sheet was spiking, predicts that if human greenhouse emissions continue unabated, by the end of this century ice loss from the Greenland ice sheet could see the ocean rise by up to 33 centimeters.

If all of the Greenland ice sheet were to melt, global sea level would rise by more than 7 meters. According to the same study, that could potentially happen within 1,000 years.

The evidence is abundantly clear: the rising temperature of the planet is causing more Arctic ice to melt during the northern summer. We cannot avoid further ice loss in coming decades, and people and ecosystems will have to adapt to this.

But there is still a window of opportunity to avoid the worst impacts of future climate change in the longer term. The evidence tells us that the only way to prevent the destruction of the Greenland ice sheet, and multi-meter rises in global sea level, is to make rapid, deep cuts to greenhouse gas emissions. That is a choice we still have a chance to make.![]()

Nerilie Abram is ARC Future Fellow in the Research School of Earth Sciences and Chief Investigator for the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes at the Australian National University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.