Traveling exhibit offers clues to how the Franklin Expedition was lost

And it explains the role Inuit played in finding the remains of its crew.

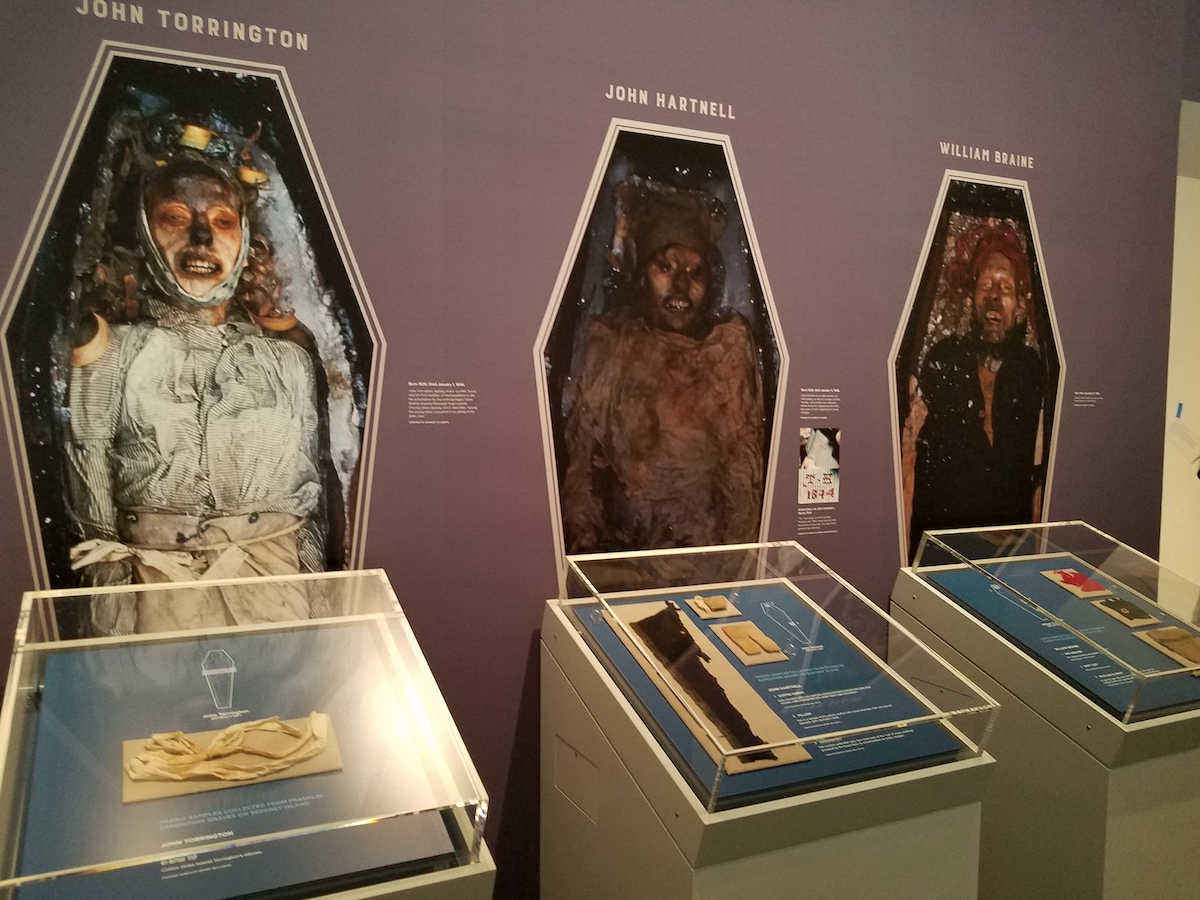

For more than a century and a half, mystery has shrouded the Franklin Expedition, a doomed attempt to find the fabled Northwest Passage. The expedition’s two ships departed England in 1845 and were abandoned three years later in the Arctic ice off Canada’s King William Island. All 129 crew members died. Left behind were scraps, broken relics, some graves and bones.

Now, after archaeological teams assembled by Parks Canada located the long-lost submerged ships in 2014 and 2016, thousands of museum visitors are able to see the remnants of the disastrous expedition.

The Anchorage Museum of History and Art is the fourth and final stop for a traveling exhibit called “Death in the Ice: The Mystery of the Franklin Expedition.” The exhibit was a collaborative project, produced by the Canadian Museum of History, the United Kingdom’s National Maritime Museum, Parks Canada, the Nunavut-based Inuit Heritage Trust and the Government of Nunavut.

The Anchorage showing, which opened on June 7 and will run through September 29, follows showings at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London, the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Quebec, and the Mystic Seaport Museum in Mystic, Connecticut.

[Franklin wreck artifacts heading to London, Ottawa for future exhibit]

The exhibit provides an up-close view of life aboard the HMS Erebus, the expedition ship found by underwater archaeologists in 2014, and the HMS Terror, the sister ship found in 2016 — and a chance to examine clues to the ultimate fate of the crew members.

“It’s a very long-lasting mystery,” said Parks Canada’s Tamara Tarasoff, project manager of the Wrecks of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror National Historic Site. “Somehow, something happened, and it didn’t work out,” she said.

That mystery has fascinated generations and provided source material for books and a recent, if embellished, horror-themed television series fittingly titled “The Terror.” It has also inspired a lot of modern criticism of the alleged hubris of ill-informed European explorers.

Exhibit curator Karen Ryan of the Canadian Museum of History considers a lot of the after-the-fact criticism to be misplaced, considering the expedition’s era and the lack of modern equipment or knowledge. “I think they were incredibly brave. I don’t think we could do it,” said Ryan, who also came to the Anchorage opening.

Items on display include the bell of the Erebus, the blue and white ceramic dishes used in crew meals, clothing and gear worn by crew members and an officer’s small prayer book. One of the most striking is kept behind protective glass: the Victory Point Note, the document that Captain John Franklin and other officers used to make notations. It was stashed in a stone cairn on King William Island. In 1847, Franklin made a now-famous notation: “All well.”

In the months to come, all would not go well, as we now know. A 1848 notation on the same paper, by Captains Francis Crozier and James Fitzjames, informs readers that Franklin died in 1847 and that his was among the two dozen deaths that occurred before the survivors abandoned the ships and started walking south. Ultimately, all perished, succumbing to starvation, possibly scurvy, possibly lead poisoning and possibly other diseases. Before they died, several members resorted to eating the flesh of their comrades, as shown by butcher marks on skeletal remains and attested by the accounts of Inuit witnesses who passed on their knowledge to succeeding generations.

[The Terror: Terribly bingeworthy]

The story is still unfolding. Parks Canada has an ongoing underwater archaeology program to keep looking for clues at the site, Tarasoff said. “I believe this year they’ll be investigating of the officers’ quarters a little more,” she said. The archaeologists will also be looking at how the ships have been transformed physically over time, she said.

There are also ambitious plans for Franklin Expedition-based tourism.

Parks Canada has partnered with the Inuit Heritage Trust on a pilot program to bring tourists to the wreck sites. In cooperation with the cruise company Adventure Canada, the passengers are to be ferried by inflatable rafts to meet up with archaeologists continuing to examine the wreckage, and then later to meet with local Inuit to learn about indigenous culture.

The program has not gone as smoothly as officials had hoped it would. Two years ago, during what was to be the first summer of trips to the Erebus wreck site, winds were too high to allow cruise passengers access, Tarasoff said. Last summer, she said, there was too much ice choking the area — showing how, even in an era of rapidly dwindling sea ice, the narrow waters threading the Canadian Arctic Archipelago are serving as a refuge for ice and ice-dependent animals. Last year, none of the seven cruise ships traveling in the Northwest Passage were able to make it even to the general region, she said.

[Parks Canada unveils the first Franklin wreck relics to be owned by Inuit]

There may be better luck for the cruises this year, with rapid ice retreat, including a record melt pace in the Beaufort Sea. “It shows the variation from year to year,” Tarasoff said. If the pilot program is successful, other cruise companies will also be able to take passengers to the archaeological sites, she said.

The tourism push is embraced by the region’s Inuit.

Barbara Okpik, a young guide from Gjoa Haven who works with the Inuit Heritage Trust, is happy to tell her people’s story. “I know a lot about my community and my background,” said Okpik, who came to Anchorage to attend the exhibit opening.

The exhibit puts a lot of emphasis on the 6,000 or so Inuit living in the Kitikmeot Region of Nunavut.

It includes accounts, passed down over generations, of their encounters with members of the Franklin expedition, described as strange men ill-equipped for the environment. The Inuit knowledge about the artifacts that had been found led to the discoveries of the ships. And there were accounts of cannibalism, conveyed back home by Scottish surgeon and Arctic expert John Rae after a search for the lost expedition. Inuit oral histories tell of starved men sitting by collections of sawed body parts of dead crewmates whose bodies they had consumed.

The condition of crew members’ bones, with butcher marks and, in some cases, signs of boiling to bring out marrow, confirms the accounts of cannibalism, modern scientists say. But in the immediate aftermath of Rae’s reports, much of the British public dismissed information provided by the Inuit.

Among the most prominent figures who rejected the reports was author Charles Dickens. In a 1854 article, he insisted that “there is no reason whatever to believe, that any of its members prolonged their existence by the dreadful expedient of eating the bodies of their dead companions” and that accounts of cannibalism were undermined by the “very loose and unreliable nature of the Esquimaux.”

[Lead poisoning probably didn’t doom the Franklin Expedition]

By now, Inuit knowledge has become better appreciated by non-natives.

Parks Canada is closely examining indigenous knowledge to try to understand why the ships found on the south side of King William Island when they had been abandoned on the north side, according to the Point Victory Note. Louie Kamookak, a Gjoa Haven hunter and Inuit historian who died recently, had a theory, according to Tarasoff. The ice on the east side of the island, according to Kamookak, has a tendency to split open and the men may have retraced their steps back to the ships and sailed south, she said.

After the Anchorage exhibit, the collected items will be returned to the various institutions that are deemed their owners. Under an agreement signed more than a decade before the Erebus was found, the first 54 items taken from the ship will go back to Britain. Other items will go to the Government of Nunavut or other entities.

Today, travel through the Northwest Passage is decidedly less rigorous than it was in Franklin’s day. Thanks to sea ice retreat caused by rapid climate warming, luxury cruise ships are making near-annual expeditions though the passage, some all the way from Greenland on the Atlantic side to Nome on the Pacific side.

One such cruise, aboard Polar Cruises ship Le Boreal, promises luxurious amenities that include a heated outdoor swimming pool, a full-service salon, a spa and a theater. Prices range from $30,000 to $68,000 per passenger.