Trump administration works toward renewed drilling in Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

The Trump administration is quietly moving to allow energy exploration in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge for the first time in more than 30 years, according to documents obtained by The Washington Post, with a draft rule that would lay the groundwork for drilling.

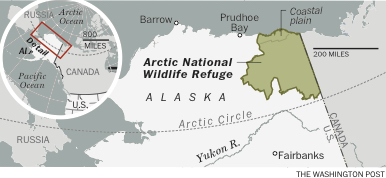

Congress has sole authority to determine whether oil and gas drilling can take place within the refuge’s 19.6 million acres. But seismic studies represent a necessary first step, and Interior Department officials are modifying a 1980s regulation to permit them.

The effort represents a twist in a political fight that has raged for decades. The remote and vast habitat, which serves as the main calving ground for one of North America’s last large caribou herds and a stop for migrating birds from six continents, has served as a rallying cry for environmentalists and some of Alaska’s native tribes. But state politicians and many Republicans in Washington have pressed to extract the billions of barrels of oil lying beneath the refuge’s coastal plain.

Democrats have managed to block them through votes in the Senate and, in one instance in 1995, by a presidential veto.

In an Aug. 11 memo, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service acting director James Kurth instructed the agency’s Alaska regional director to update a rule that allowed exploratory drilling between Oct. 1, 1984, and May 31, 1986, by striking those calendar constraints.

Doing so would eliminate an obstacle that was the subject of a court battle as recently as two years ago.

“When finalized, the new regulation will allow for applicants to [submit] requests for approval of new exploration plans,” Kurth wrote in the memo.

If the rule is finalized after a public comment period, companies would have to bid on conducting the seismic studies. The U.S. Geological Survey estimated in a June 27 memo, obtained by Trustees for Alaska through a federal records request, that this work would cost about $3.6 million.

With oil prices averaging around $50 per barrel, potentially too low to justify a significant investment in drilling in the refuge, it is unclear how much interest companies would have. Some might consider proceeding with those studies to get a better sense of the area’s potential.

The behind-the-scenes push to open up the refuge – often referred to by its acronym, ANWR – comes as longtime drilling proponents occupy key positions at the Interior Department.

Its No. 2 official, David Bernhardt, represented Alaska in its unsuccessful 2014 suit to force then-Interior Secretary Sally Jewell to allow exploratory drilling there. Joseph Balash, President Trump’s nominee to serve as Interior assistant secretary for land and minerals management, asked federal officials to turn a portion of the refuge over to the state when he served as Alaska’s natural resources commissioner. The state’s plan was to offer the land for leasing.

During a stop in Anchorage on May 31, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke said he hoped to jump-start energy exploration on Alaska’s North Slope in part by updating resource assessments of the refuge.

“I’m a geologist. Science is a wonderful thing. It helps us understand what is going on deep below the surface of the Earth,” Zinke said at the time. “We need to use science to update our understanding of the [coastal plain] of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge as Congress considers important legislation to responsibly develop there one day.”

The Fish and Wildlife memo notes that the Interior Department asked it “to update the regulations concerning the geological and geophysical exploration” of that coastal area but does not identify who issued the directive.

An Interior officialsaid in an email Friday that the department is “required by law – the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act – to allow for seismic surveys in wildlife refuges across Alaska.”

“Hundreds of seismic surveys have been conducted on Alaska’s north slope – many of them on ANWR’s borders,” the official added.

Both the Clinton and Obama administrations concluded that the department was legally barred from permitting seismic studies in the refuge. And environmentalists have consistently opposed such activity, which sends shock waves underground. They say it would disturb denning polar bears, which are listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act, as well as musk oxen and other Arctic animals.

An increasing number of polar bears are now denning onshore during the winter – when seismic studies would take place – due to diminishing sea ice, and a significant portion of the coastal plain is designated as critical habitat for the bears. The Aug. 11 memo directs the Fish and Wildlife Service’s regional director to conduct an environmental assessment as part of the proposed rule change because the Endangered Species Act requires federal agencies to show that their actions will not jeopardize or adversely modify critical habitat of a listed species.

“The administration is very stealthily trying to move forward with drilling on the Arctic’s coastal plain,” said Defenders of Wildlife President Jamie Rappaport Clark, who led the Fish and Wildlife Service under President Bill Clinton. “This is a complete about-face from decades of practice.”

Environmental groups would be likely to challenge any decision to conduct seismic work in the refuge in federal court.

Alaska officials have been working for several years to restart seismic studies on the coastal plain. They say the initial ones, conducted in the winters of 1984 and 1985, were done with outdated technology and do not reflect the area’s true potential. The Geological Survey, which reanalyzed that data nearly 15 years later, estimated that 7.7 billion barrels of “technically recoverable oil” lie under the coastal plain.

The June 27 memo, sent to Zinke’s energy policy counselor Vincent DeVito, said the department could either assume the existing seismic data is acceptable, reexamine that data with “state-of-the-art” technology or conduct new studies with modern, 3-D technology.

In an interview Thursday, Alaska Natural Resources Commissioner Andy Mack said that recent oil discoveries near the refuge’s western edge suggest there may be more oil there than federal officials identified three decades ago.

“Alaska’s always had an abiding interest in resource development, particularly in oil,” Mack said. “We’re not discounting the existing data, but it’s old, and it’s relatively limited.”

The question of whether Interior can restart the seismic work is a subject of legal dispute. The 1980s studies, which took place along 1,400 miles of survey lines and were financed by private oil firms, were aimed at gathering information for a report the interior secretary submitted to Congress in 1987.

In 2001, Interior solicitor John Leshy issued a formal opinion concluding that the 1983 rule was “a time-limited authorization for exploratory activities in the coastal plain.”

Twelve years later, Alaska sought permission from the Fish and Wildlife Service to launch a new exploration program; Obama administration officials rejected the request, and the state sued.

On July 21, 2015, U.S. District Judge Sharon Gleason ruled against the state. “Whether the statute authorizes or requires the Secretary to approve additional exploration after the submission of the 1987 report is ambiguous,” she wrote, but Jewell’s interpretation that she no longer had authority to allow it “is based on a permissible and reasonable construction of the statute.”

Mack said he was not sure whether companies would want to drill in the refuge, but they now are more interested in the potential on land than offshore.

ConocoPhillips, for one, is “actively exploring and focused on new development opportunities” within the neighboring National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska, according to spokesman Daren Beaudo. “If ANWR was opened, we’d consider it within our portfolio of opportunities . . . and it would have to compete with other regions for our exploration dollars,” he said.

Yet Pavel Molchanov, an energy analyst at Raymond James & Associates, predicted “very little interest” in drilling in the refuge for the foreseeable future.

“The number of companies that would be open to a meaningful bet on ANWR we could realistically count on one hand, and that would be generous,” Molchanov said.