How Trump’s trade war hurts Alaska’s bid to build a gas line from the Arctic

ANALYSIS: Expensive, long-term projects such as Alaska's long-proposed gas line rely on clarity and certainty. This trade war injects chaos and uncertainty.

The shooting has started in the U.S. trade war with China and no one can say when it will stop or how bad it will get.

A few stray shots have already landed in Alaska, perhaps with more to come.

Despite comments to the contrary from Alaska officials struggling to keep up a good front, the trade fight spells trouble for the scheduling of the proposed $43 billion natural gas pipeline linking Arctic gas fields to liquefaction and port facilities in the southcentral part of the state.

The Trump trade war won’t necessarily halt one of the largest proposed energy projects in the U.S. — but it will hinder negotiations over it.

The trade war has injected confusion and uncertainty into a complicated process that requires clarity and certainty. The business deal of getting Alaska’s Arctic gas supply to market requires long-term contracts and binding financial commitments.

The more confusion and uncertainty, the lower the chance that Alaska can reach lasting contracts with government-backed entities in China that protect the interests of Alaskans in the sale of North Slope gas.

China offers the best potential market for Alaska gas as its demand is expected to increase at 7 percent a year through 2025, according to the Wood Mackenzie consulting company.

And global demand for LNG is expected to exceed supply within five years, but it’s not as if Alaska is the only option for buyers.

There are many competing projects around the world not at risk from the protectionist crossfire, including a major venture in British Columbia.

The problem that overrides all of the economic arguments is that national and international politics have to be accounted for.

Businesses developing plans for the next year or two do not have the information they need today to gain confidence in U.S. trade policies.

Those that need guidance to look decades ahead face an impossible challenge under President Donald Trump.

Trump has failed to define objectives for his trade war or offer any strategy about how to end it.

That leaves everyone guessing, which is incompatible with a resource development project that could impact Alaska’s economy for generations.

“We can no longer be the stupid country,” Trump declared in a speech to the National Federation of Independent Business in Washington. “We want to be the smart country.”

Part of becoming a “smart country” is developing reasonable and reliable trade, but the U.S. has yet to wise up.

The Trump administration has given conflicting signals on its approach to China. Its competing factions include some advisors who favor open trade and others who want to punish China.

The open hostilities began in early July as each country slapped a 25 percent tariff on $34 billion worth of trade goods.

Trump has threatened additional tariffs on more than $500 billion of Chinese goods. He has claimed that trade wars are easy to win, but the experts deride that as foolish talk.

For its part, China has threatened tariffs on energy imports, a prospect that would not help Alaska’s case.

While the immediate impact on Alaska arrived in the form of a punishing 25 percent tariff on seafood bound for China, the gas pipeline effort has been dealt a setback by this tit-for-tat exchange.

Alaska does more than $1 billion a year of business with China, about 60 percent of it in the form of exported seafood, with about $400 million in mineral ores and energy.

The state is looking to increase energy exports by hundreds of billions, a vision that requires major capital investment by the Chinese.

China has signed non-binding pledges with Alaska to provide 75 percent of the funding in exchange for 75 percent of the liquefied natural gas from Alaska.

The non-binding pledges are similar to many that have been produced and abandoned in the decades since the gas pipeline promotional activities began.

The tentative schedule of signing binding commitments by the end of this year has been thrown into doubt because it’s not clear if the trade war will last months or years or if the sides will compromise.

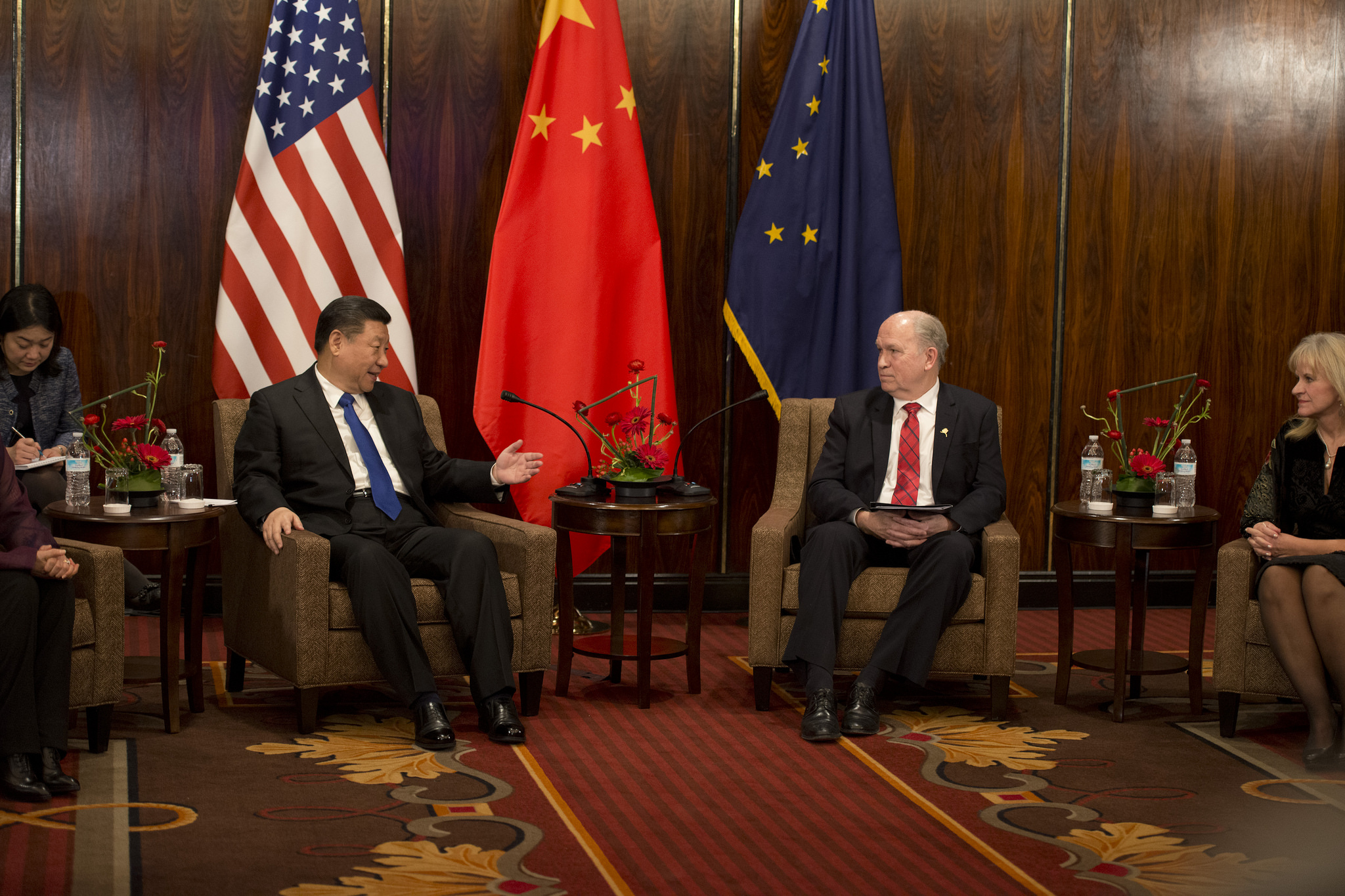

Walker, ever the true believer in exporting Alaska natural gas, says that China wants access to the reserves on the North Slope.

It sees the value of long-term contracts with a stable price and a stable government.

“I think this transcends the current discussion on trade issues,” Walker told reporters in June.

Clearly, the Alaska governor would like the gas pipeline to transcend the international squabble, but until the U.S. and China settle their dispute, don’t look for binding agreements on the gas pipeline totaling tens of billions of dollars.

And the governor, who has based his entire political career on getting a gas pipeline, must resist the temptation to give away Alaska’s resources in the belief that any pipeline deal is superior to no deal.

Walker says the state is trying to speed up negotiations.

In the meantime, look for more agreements with escape clauses and enough wiggle room to allow both sides justify claims that progress is taking place while the chaotic trade war runs its course.

Columnist Dermot Cole can be reached at de*********@gm***.com.