‘Tundra be dammed’: Beavers are following shrubs into Arctic tundra landscapes

“Suddenly, a beaver shows up and it’s like hitting the landscape with a hammer.”

North American beavers, the wood-chomping denizens of the forests, are moving into the Arctic as woody shrubs spread across the tundra.

Scientists with the University of Alaska Fairbanks, U.S. Geological Survey and other institutions have documented 56 beaver complexes that have been built since 1999 along rivers and creeks in Arctic northwestern Alaska.

The findings are detailed in a study published in the journal Global Change Biology that has a provocative and descriptive title: “Tundra be dammed.”

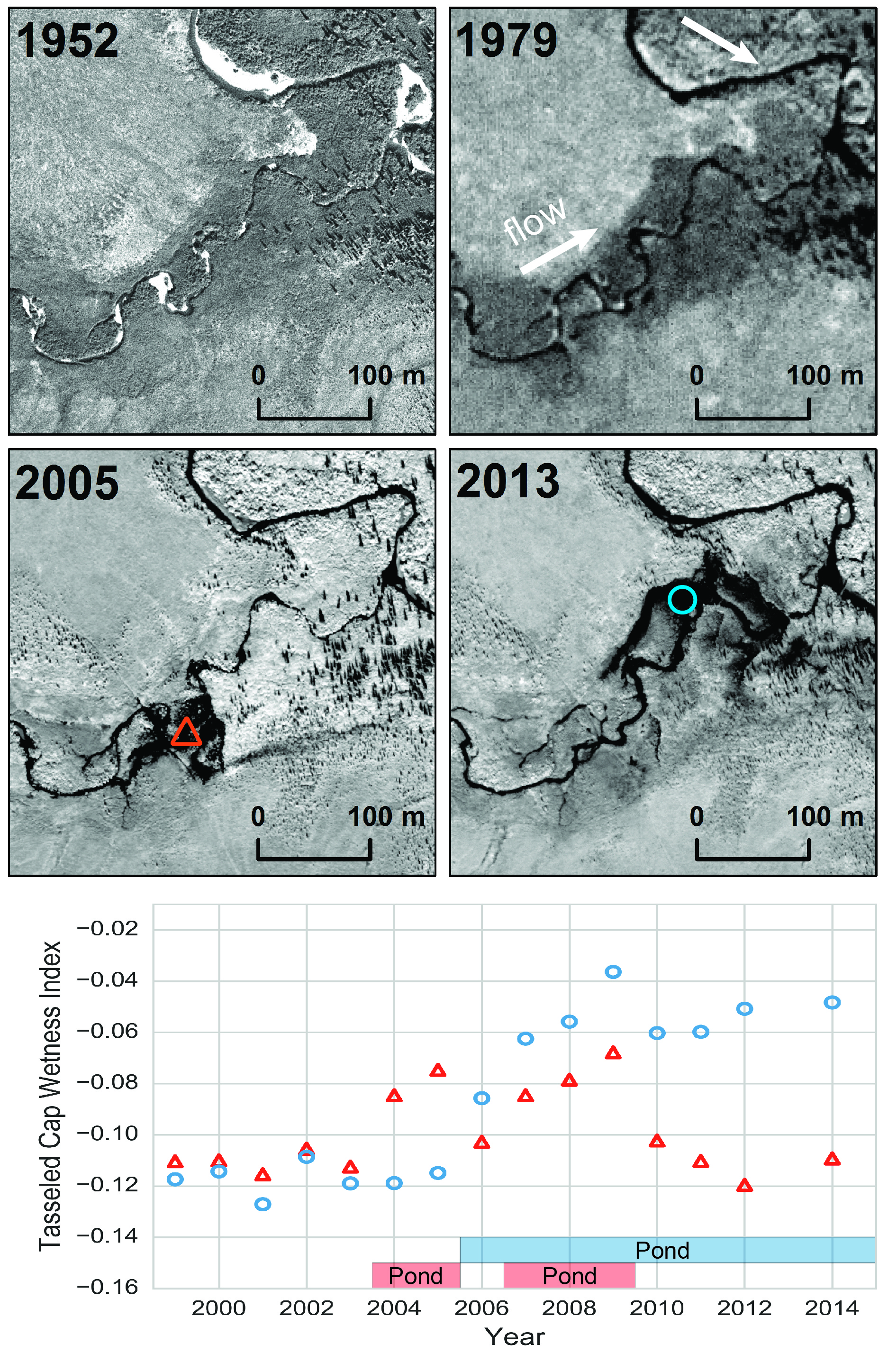

The study uses satellite imagery along the three river watersheds in northwestern Alaska, and it describes how beavers are “agents of disturbance” in the Arctic tundra ecosystem.

Other boreal animals, like moose and snowshoe hares, have also been following shrubs into the Arctic, said University of Alaska Fairbanks ecologist Ken Tape, the study’s first author and an expert in the encroachment of other species into the far north.

Those other boreal species, through their browsing, traveling or nesting behavior, can exacerbate changes to the habitat gradually and over the long term, Tape said. But beavers are special to scientists because their presence and impacts are anything but subtle, he said.

“Suddenly, a beaver shows up and it’s like hitting the landscape with a hammer,” he said.

Beaver dams and lodges can be seen from space — as the Tundra Be Dammed study shows — and their construction activities trigger more forces of warming that feed into the climate-change and habitat-change cycle.

The new beaver ponds are deeper, resisting freeze and making thaw of the permafrost below the water more likely, for example.

“In the Arctic, you put a pond where before you had a stream, and immediately you submerge a bunch of permafrost, in some cases, ice-rich permafrost,” Tape said. “We know that when you put a pond on the landscape like this, you’re going to induce permafrost thaw.”

Changes made by beavers likely affect other species, both positively and negatively, he said. The ponds created by dams can be “boreal oases of warmth,” potentially attracting boreal fish like salmon. Beavers’ construction can also impede movement of other fish, like the whitefish species that are an important part of Arctic subsistence diets, he said.

While there has been much study of Lower 48 beavers’ impacts to fish populations, there has been no such study in the Arctic, Tape noted.

For Arctic people, the beaver newcomers are a source of concern. The rivers and streams are people’s transportation routes, both in winter freeze and summer flow, so beaver structures are potential problems, Tape said.

Health officials also worry about the expansion of giardiasis, an intestinal disease commonly called “beaver fever,” and other zoonotic diseases that might make drinking-water sources unsafe. The Centers for Disease Control’s Arctic Investigations Program is monitoring giardiasis and other diseases that might be spreading as the climate warms and beavers and other boreal animal species expand their range.

Beaver expansion into tundra habitat has been detected elsewhere in Arctic North America. On the northern tip of Canada’s Yukon Territory, wildlife managers in 2015 came across a beaver dam, lodge and winter food cache complex that turned out to be the first ever documented on the Beaufort Sea coastal plain.

One place where beavers have not yet been found is Alaska’s North Slope, Tape said. “It’s one of the last areas of the U.S. that’s not colonized by beavers,” he said.

Yereth Rosen is a 2018 Alicia Patterson Foundation fellow.