As climate changes, US admirals see increasing need for Arctic presence

The phrase “climate change” doesn’t appear once in recently released Arctic strategies from the Coast Guard and the Navy, but military leaders are preparing for it nonetheless.

Although the new Arctic strategies from the Navy and the Coast Guard highlight rapid changes in the region, they also both shy away from attributing many of the increasing challenges to climate change. But admirals from the two services recently spoke to increasing demands for presence in the region — which they explicitly attributed to climate change.

Earlier this month at the Sea-Air-Space exposition near Washington, D.C., maritime leaders addressed the question directly.

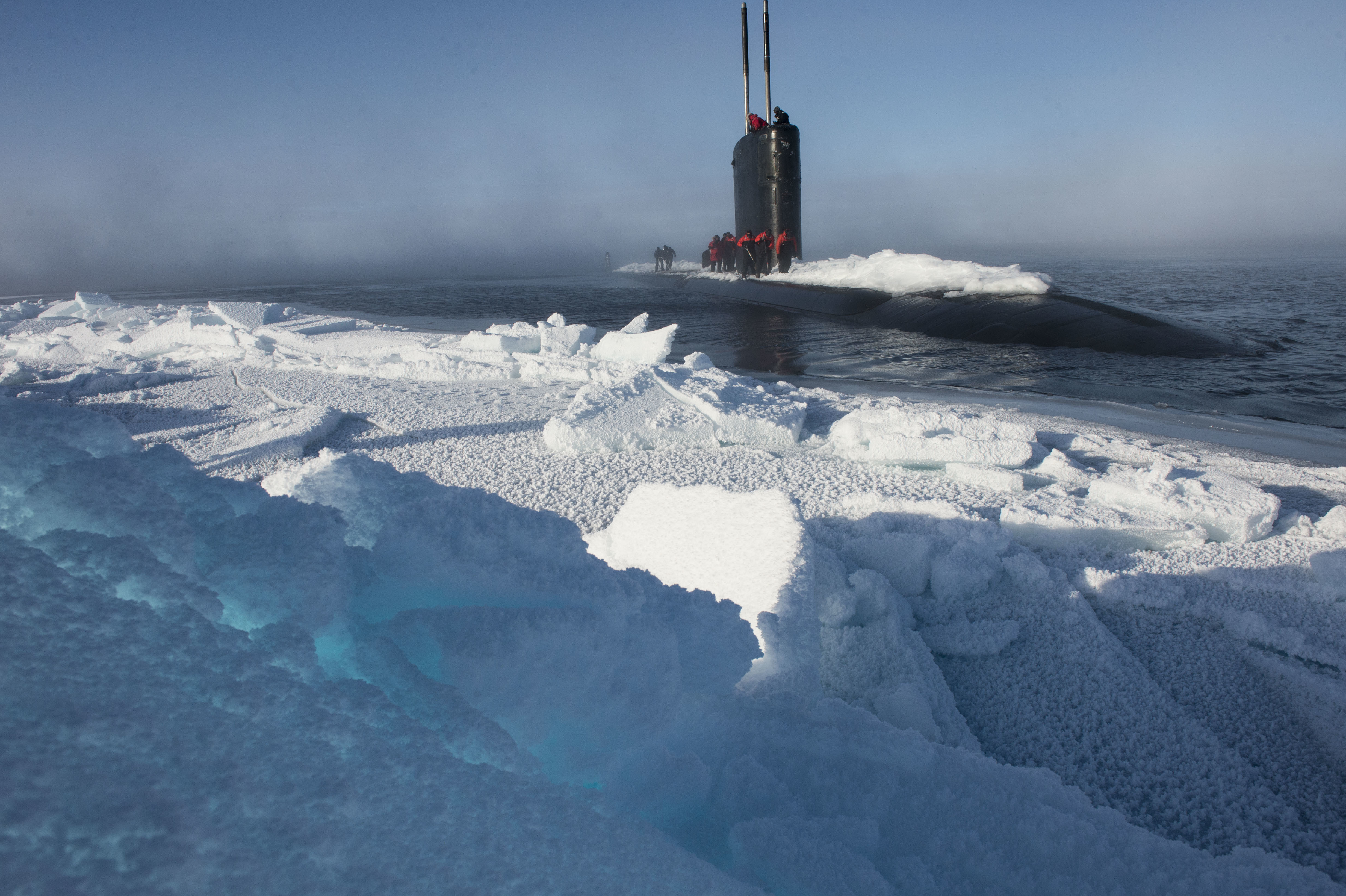

“The Arctic is a very dynamic situation in response to this climate change,” said Adm. John Richardson, the chief of naval operations for the Navy. “Seaways are open that weren’t open before — had not been open in our lifetime. The Arctic ice cap is as small as it’s ever been since we started measuring it. Continental shelves that are exposed that were not exposed before.”

[The U.S. Navy’s new Arctic strategy is limited in scope and details, say critics]

The changes mandate a response from U.S. maritime forces in particular, he said.

Richardson also spoke about the importance of resilient infrastructure.

“Anything new, really, is built to standards that accommodate climate change,” he said, and “legacy infrastructure” that already exists is being updated as much as possible.

And he addressed the importance of working with the community in this process. “Because we’re not just an island unto ourselves,” he said. “Most of the time, there’s a community that’s affected” — and those communities are also working to adjust to these changes.

Adm. Karl Schultz, commandant of the Coast Guard, agreed on the importance of climate resilience. During Hurricane Harvey in 2017, for instance, having a new, modern facility helped the service rescue thousands of people in Houston.

“A modern facility — a resilient facility — was game-changing,” Schultz said. “Those investments are absolutely essential.”

[The U.S. Coast Guard’s new Arctic strategy highlights geopolitics and security]

Schultz shied away from the phrase “climate change” — the one time he mentioned it, he immediately interjected a disclaimer that the science was up for argument — but he said that long-term plans had to factor in the latest resilience innovations.

“When we get a bite of the apple, we’re investing for probably half a century,” he said. “We need to inform our thinking now with the best knowledge we can, and we’re bringing that into our design work.”

In the Arctic, he said, “there is a demand signal up there,” and their access in all seasons — not just during the shoulder season — needs to improve.

At a panel following the maritime leaders’ remarks, other officials from the Navy and the Coast Guard elaborated on the agencies’ climate strategies.

“The Coast Guard philosophy is the fact it’s undeniable conditions are changing up there,” said Vice Adm. Dan Abel. Like Schultz, he deferred a discussion on why the climate is changing.

“I’m not going to get into the science behind it, but I’m into the so-what and what-next?” he said. “How are we going to operate there, and how are we going to do what our nation needs?”

[Understanding climate change is key to Arctic diplomacy, experts say]

Rear Adm. John Okon, a Navy meteorologist, spoke to the “extremely extreme” conditions in the Arctic that make it difficult both to operate in the region and to predict changes. Yet the changing environment in the Arctic “underpins everything we’ve talked about,” he said. “You better understand the environment you’re operating in.”

The meteorological observations the U.S. takes in the Arctic are equivalent to data collected over the continental U.S. during the First World War, Okon said. “We’re a hundred years behind in understanding and observing the conditions in which we know we are going to have to defend our homeland and work with our partners.”

The Department of Defense is due to release an updated Arctic strategy no later than June 1, and Arctic strategies from both the Navy and the Coast Guard will likely be integral in the document.

But both strategic outlooks skirt discussions of climate change in an increasingly open Arctic — or their plans to address it. The Navy does mention “environmental change,” which covers a wide range of physical changes, and the Coast Guard points to a “changing climate and growing human activity” to increasingly frequent and severe incidents facing Arctic communities.

[Will the Arctic Council begin addressing national security?]

Yet without acknowledging climate change specifically as a major driver to the changes in the Arctic, it is difficult to create and execute long-term strategies in the region–and it may put U.S. national security at risk, Sherri Goodman says.

“The reason that the space has become competitive is because of climate change,” Goodman, senior fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center and former U.S. deputy under-secretary of defense, recently explained in a briefing. “Climate change indeed has created a threat multiplier in this region.”

“Let’s be clear about why we are having to increase presence there,” Goodman told ArcticToday. “It’s because climate change has caused sea ice to retreat and temperatures to warm.”

Goodman pointed to the Trump administration’s policy of avoiding climate change directly in official documents.

“Word-smithing is done to avoid issues with those at the White House who don’t want to talk about it,” she said. “But everyone else knows it’s happening and has recognized it — in the Coast Guard, in the Department of Defense and in the intelligence community.”