U.S. and Russia sign new maritime pollution agreement, conduct joint Bering Sea patrol

The U.S. Coast Guard is collaborating with Russian counterparts on transboundary pollution and maritime boundary patrols in the region.

The U.S. Coast Guard and the Russia’s Marine Rescue Service have agreed to an updated plan to address maritime pollution across international boundaries in the Chukchi and Bering seas.

The agreement comes days after the Coast Guard and Russia’s Border Guard completed a joint patrol of the maritime boundary line between the two countries.

On Feb. 1, the two maritime services signed an updated agreement to the bilateral Joint Contingency Plan, first established in 1989, to plan, prepare and respond to transboundary maritime pollution incidents.

The agreement “promotes the protection of our shared interests in these environmentally and culturally significant trans-boundary waters,” said Vice Adm. Scott Buschman, U.S. Coast Guard deputy commandant for operations, in a statement. It creates mechanisms for better cross-border cooperation between the two services, including creating “International Coordinating Officer” role to help share information.

Other agreements between the U.S. and Russia include search-and-rescue missions and countering illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing.

The U.S. and Russian services plan to hold joint training exercises to prepare for pollution response in the near future, he said.

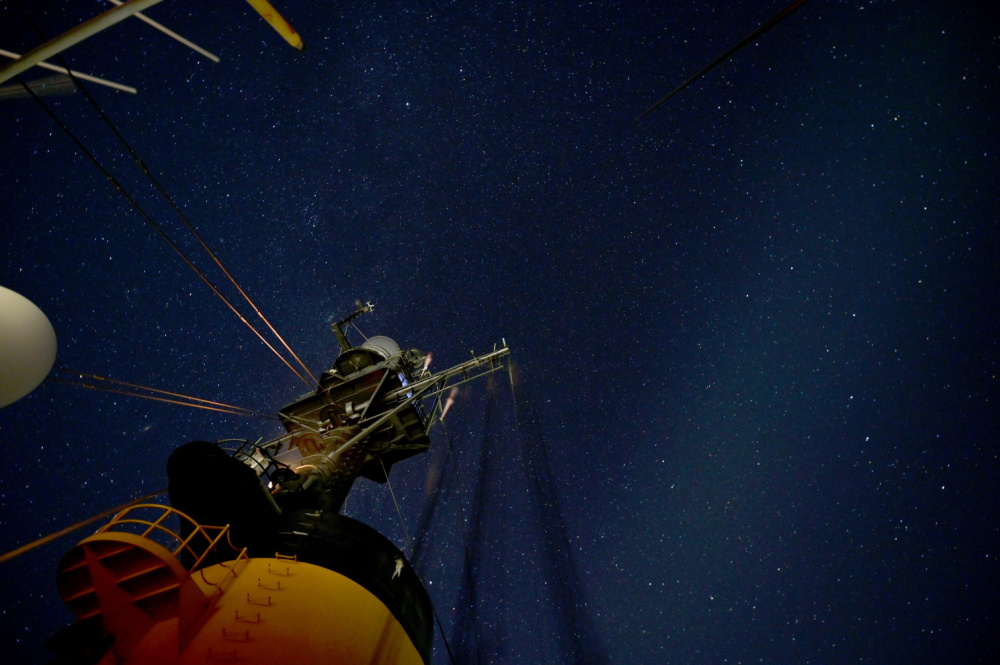

In mid-January, Polar Star also patrolled the boundary line in the Bering Sea with Russian aircraft in a joint communications exercise between the U.S. Coast Guard and the Russian Border Guard.

The Coast Guard has detected one Russian fishing vessel crossing the maritime boundary line in recent years. The Russian Border Guard promptly investigated the incursion and issued fines.

Capt. Jason Brennell, chief of enforcement for the Coast Guard’s Seventeenth District, highlighted in a statement the service’s “unique cooperative relationship” with Russian counterparts. Agreements like these shore up important relationships between the two countries’ services, he said.

The maritime boundary between the U.S. and Russia in the Bering and Chukchi seas can be difficult to access because of poor weather and seasonal conditions. Both countries have limited resources for responding to incidents — from pollution to illegal fishing — in these waters.

The pollution agreement is particularly important given the sensitive nature of the Bering Sea ecosystem, Troy Bouffard, director of the Center for Arctic Security and Resilience at University of Alaska Fairbanks, told ArcticToday.

“They’re now in a better position to enforce those new pollution aspects of the Polar Code,” he said.

Agreements like these also help maintain the Arctic’s status as an arena of international cooperation.

“This kind of particular cooperation and these efforts that happen at the Coast Guard level are very separate and distinct from the defense organizations,” Bouffard said.

Members of the Arctic Coast Guard Forum have been careful to keep military issues from encroaching on the collaborative agreements they have reached, he said.

The Coast Guard’s growing rhetoric of geopolitical competition and conflict in the Arctic during the Trump administration made it trickier to navigate this collaboration, Bouffard said, but the service continues to shore up agreements that encourage international cooperation in the region.

One particular source of contention has been addressing illegal actions in the region that aren’t state-sanctioned. “It’s hard to go to a state and say, ‘Hey, you need to control your criminals — they’re polluting or they’re fishing illegally.’ It just doesn’t work that way,” Bouffard said.

But agreements like these can send a message about unacceptable behaviors. “These agreements are a very effective signal of what’s being emphasized and prioritized,” he said. “The deterrence factor is the kind of thing that makes your bad actors think twice.”

In a region like the Arctic, with vast physical and operational challenge, nations working together is critical, Bouffard said.

“They have to share information,” he said. “If they don’t, it’s just going to be absolutely impossible to have domain awareness and an ability to actually intervene as needed.”

International agreements can also help prevent incidents, like pollution spills from cruise ships, that can be difficult to manage once they occur.

“Like many other things in the Arctic, the most important thing to do is to prevent, because the response piece of anything in the Arctic is always extra difficult and expensive,” Bouffard said. “So, there are huge dividends to be gained by preventing emergencies and potential security issues.”