U.S. Coast Guard chief warns of Russian ‘checkmate’ in Arctic

The commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard issued a stark warning on Wednesday that Russia was leagues ahead of Washington in the Arctic. And while the warming Arctic opens up, the United States could be caught flat-footed while other geopolitical rivals swiftly step in.

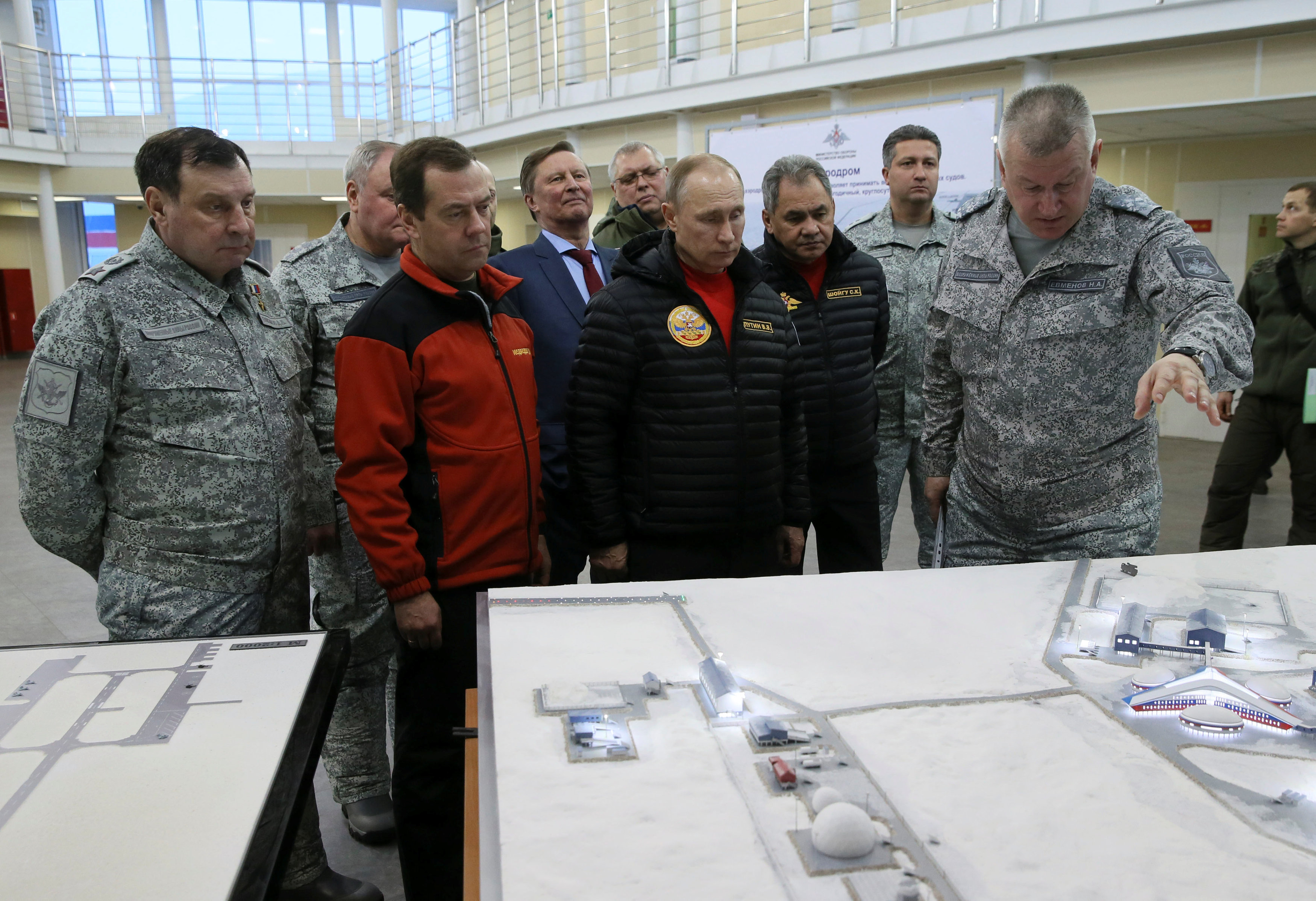

Paul Zukunft, commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard, warned Russia was building up a huge military and industrial presence in the region while the United States dawdled. Russia is showing “I’m here first, and everyone else, you’re going to be playing catch-up for a generation to catch up to me first,” said Zukunft in remarks before the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “They’ve made a strategic statement,” he said.

Take icebreakers, specialized ships that can punch through thick Arctic ice and ensure access to sea lanes for both commercial and military ships. Russia has 40, while the United States has only two in service today, and only one really available for the Arctic.

As Arctic ice recedes, it’s opening access to a rich bed of natural resources other countries like Russia and China are hungrily eyeing: An estimated 30 percent of the world’s untapped gas reserves, 13 percent of the oil reserves, and $1 trillion in minerals. The United States will struggle to keep other geopolitical rivals from filling the void without a proper Arctic footprint, Zukunft warned.

The Polar Star, the last remaining U.S. heavy icebreaker built in the 1970’s, is well past its prime. “Having only one heavy icebreaker…it is the one aspect I lose sleep over,” he said. Zukunft is pushing for funding from Congress to build six new icebreakers by 2023, high aims given the Coast Guard’s rocky start in the federal budget process.

He even said a new icebreaker fleet could need “offensive and defense armed capability” to hedge against any sort of showdown with Russia. But that’s all in the distant future, and if the Polar Star breaks down there’s little left in the U.S. inventory to take its place.

All the while, Russia is slated to launch two icebreaking corvette-class ships armed with cruise missiles in the next several years. “We’re not building anything in the Navy surface fleet to counteract that,” Zukunft said.

That doesn’t mean Russia’s buildup is directed at U.S. Arctic territory around Alaska; most of its chess pieces are with its Northern fleet in the west, pointed toward Europe and the Atlantic. “Russia’s Pacific fleet is rather under-resourced compared to the Northern fleet,” said Magnus Nordenman, director of the Atlantic Council’s Transatlantic Security Initiative.

And Russia isn’t only bulking up its Arctic footprint for nefarious geopolitical gains against its former Cold War rival. “Their build up makes economic sense. It’s a key region for Russia’s economy, 20 percent of its GDP comes out of the Arctic,” Nordenman told Foreign Policy.

Still, Zukunft is worried if things go south in the high north, Russia will have a big leg up on the United States.

“They’ve got all their chess pieces on the board right now, and right now we’ve got a pawn and maybe a rook,” he said. “If you look at this Arctic game of chess, they’ve got us at checkmate right at the very beginning.”