U.S. rhetoric about the strategic importance of the Arctic is out of step with its spending priorities

American rhetoric is turning up the temperature in the Arctic while not even really putting its money where its mouth is.

On Tuesday, the U.S. Senate resumed consideration of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for 2020. This is the bill that sets the annual budget for the U.S. Department of Defense, which receives more than half of all of the federal government’s discretionary funding each year. Each year, the NDAA also offers an update of the government’s perceived threats to national security.

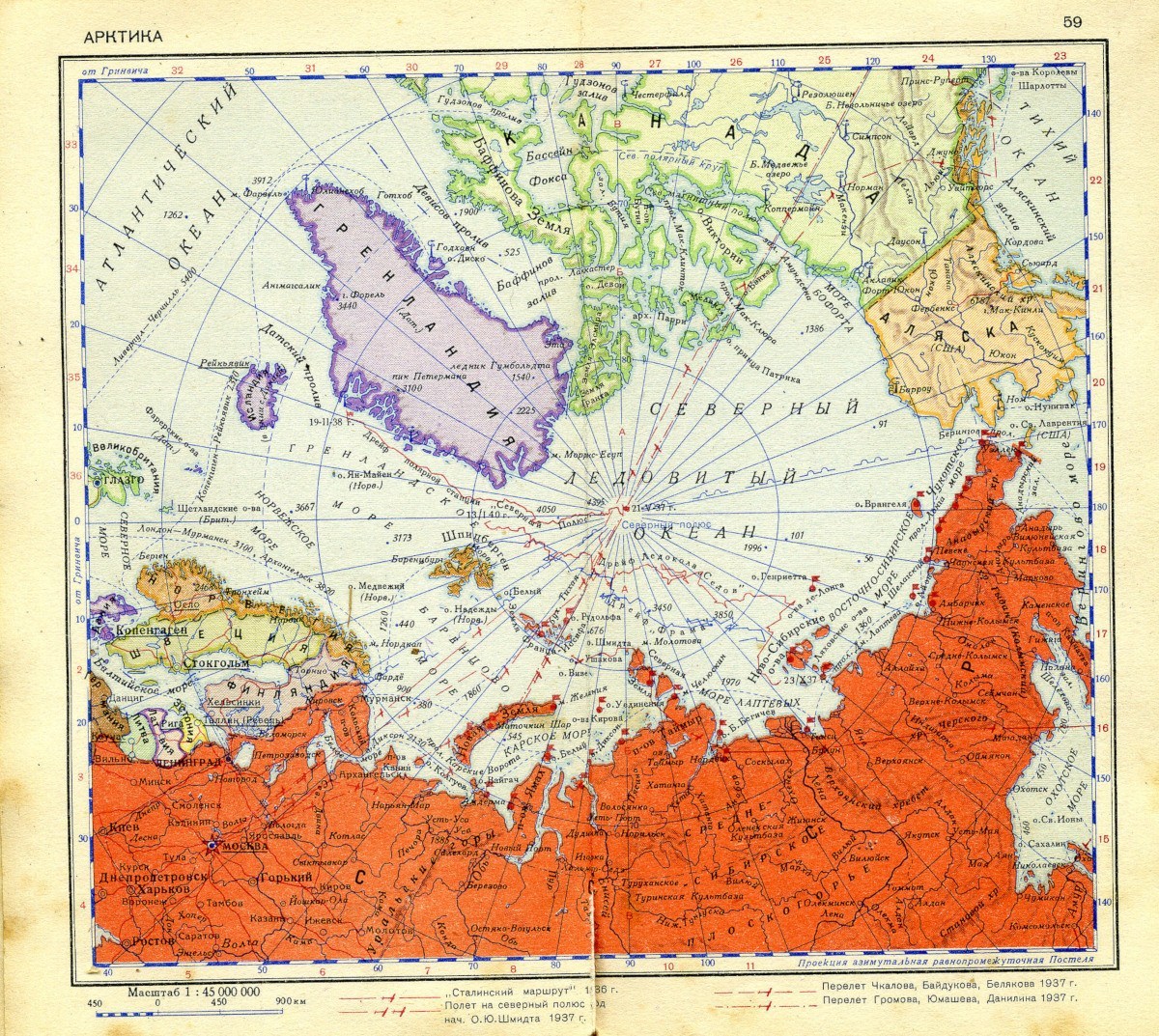

Comparing this year’s NDAA to last year’s shows how high the Arctic has risen on Congress’ radar. Whereas this year, the NDAA mentions the word “Arctic” 89 times, in 2018, it was only stated 20 times, largely in reference to requiring a report on an updated Arctic Strategy from the Secretary of Defense. That report finally came out on earlier this month, describing itself as being “anchored in the priorities of the 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS) and its focus on competition with China and Russia as the principal challenge to long-term U.S. security and prosperity.” This reflects the growing perception within the Beltway that China and Russia present the main challenges to American superpower, a threat the report called “great power aggression.”

[A new U.S. Defense Department Arctic Strategy sees growing uncertainty and tension in the region]

The Secretary of Defense’s report on its Arctic Strategy went on to identify the central problem facing the Joint Force: its “eroding competitive edge against China and Russia.” That edge is not just metaphorical. It literally is dissolving in the Arctic, too. The NDAA 2020 quotes General John Hyten, Commander of the U.S. Strategic Command, as saying earlier this year during testimony to the U.S. Senate:

“In particular, the Arctic is an area that we really need to focus on and really look at investing. That is no longer a buffer zone. We need to be able to operate there. We need to be able to communicate there. We need to have a presence there that we have not invested in in the same way that our adversaries have. And they see that as a vulnerability from us, whereas it is becoming a strength for them and it is a weakness for us, we need to flip that equation.”

The escalation of rhetoric by U.S. military officials is striking, especially when contrasted with what Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev declared in his 1987 Murmansk Speech, four years before the USSR collapsed:

“Let the North of the globe, the Arctic, become a zone of peace.”

In the eyes of U.S. defense commanders, nearly 30 years of relatively peaceful relations in the Arctic appear to be dissolving. From their perspective, the Arctic is no longer a “zone of peace.” In fact, in the words of General Hyten, it is not even a “buffer zone.” It is instead a crumbling cliff-edge that may potentially pit the U.S., China, and Russia head to head.

This alarmist rhetoric is not unique to General Hyten. At the same meeting in February 2019 where he was delivering testimony to the Senate, General Terrence O’Shaughnessy, Commander of the U.S. Northern Command, expressed:

“I view the Arctic as the front line in the defense of the United States and Canada.”

The NDAA’s talk of front lines and also “sea lanes” and “choke points” re-envisions the Arctic as a battleground, one in which geopolitics is a zero-sum game. The Arctic of today’s American commanders seems to be less one of Parag Khanna’s Connectography and more one of Halford Mackinder’s Geographical Pivot of History. There’s no longer a fuzzy zone in which Western and non-Western great powers can co-exist — especially if they are not Arctic states. Rather snidely, the NDAA reminds that China “declares itself as a ‘’near-Arctic state’, even though its nearest territory to the Arctic is 900 miles away.”

China, for its part, constantly underscores its commitment to peace in the Arctic. The country’s Arctic Policy, released in 2018, notes that the government wishes to “build a community with a shared future for mankind and contribute to peace, stability and sustainable development in the Arctic.” In many ways, China’s policy resembles Gorbachev’s Murmansk Speech in which he noted, “The community and interrelationship of the interests of our entire world is felt in the northern part of the globe, in the Arctic, perhaps more than anywhere else.”

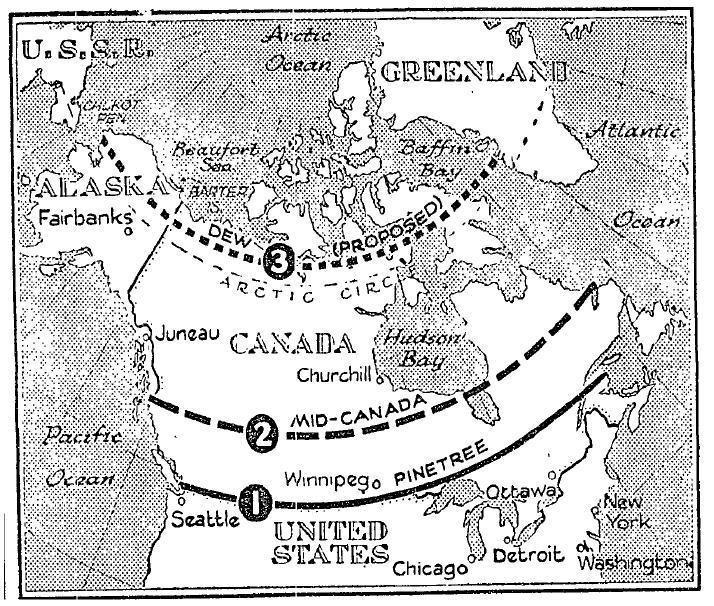

From the vantage point of Washington, D.C. in 2019, it appears that the Arctic community is fracturing along hardening lines. The National Security Strategy describes China and Russia as “revisionist powers,” but the irony is that at least in terms of rhetoric, it is the U.S. which seems to be reverting to Cold War-era talk of containment, lines, choke points, and dominos. The 2019 NDAA’s pronouncement that the government must soon identify “strategic Arctic ports” recalls the U.S. and Canada’s construction of the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line in the 1950s and 1960s. This series of 63 stations built along the 69th parallel from Alaska to Greenland was meant to warn against Soviet nuclear missile attacks coming through the frigid Arctic air. Now, the forthcoming strategic Arctic ports may be meant to prevent incursions made via an increasingly open, warming, and acidifying sea.

There is no denying that China and Russia are in fact investing in new assets in the Arctic, from joint cooperation on the Yamal liquefied natural gas project to new icebreakers for both countries (one for China and four for Russia, with another eight planned), and 16 refurbished or newly built deepwater ports and 14 airfields for Russia.

Yet in contrast, the U.S. seems to be rattling its saber without fiscal contributions to back up its fearful words. The language of the NDAA does not project of image of American strength in the Arctic. Instead, all of the reports informing the NDAA 2020 and the proposed budget itself betray the government’s anxiety over the shifting geopolitics of the Arctic. It also suggests an ignorance that much of the growing interest from Russia and China in the Arctic stems from not so much a desire to militarize the region, but rather to use economically develop it by exploiting its shipping lanes and resources.

The U.S. has little to gain from participating in the development of the Northern Sea Route. It also would likely not benefit in the near term from investing in the Northwest Passage with Canada, which is a more difficult passage to traverse and which does not offer a lucrative shortcut between Europe and Asia. As such, it doesn’t make sense currently for the U.S. to try to build up Alaska’s coastline to support a great deal more maritime activity (at least until, say, the Transpolar Passage comes closer to reality).

In the meantime, and disappointingly, American rhetoric is only turning up the temperature while not even really putting its money where its mouth is.

Mia Bennet is assistant professor of geography at Hong Kong University’s School of Modern Languages and Cultures, and writes at Cryopolitics, where this piece first appeared. It is republished here with permission.

The views expressed here are the writer’s and are not necessarily endorsed by ArcticToday, which welcomes a broad range of viewpoints. To submit a piece for consideration, email commentary (at) arctictoday.com.