Texting in Alaska Native languages? It just got easier thanks to a new app.

Two Alaska brothers are bringing Alaska Native languages further into the digital world.

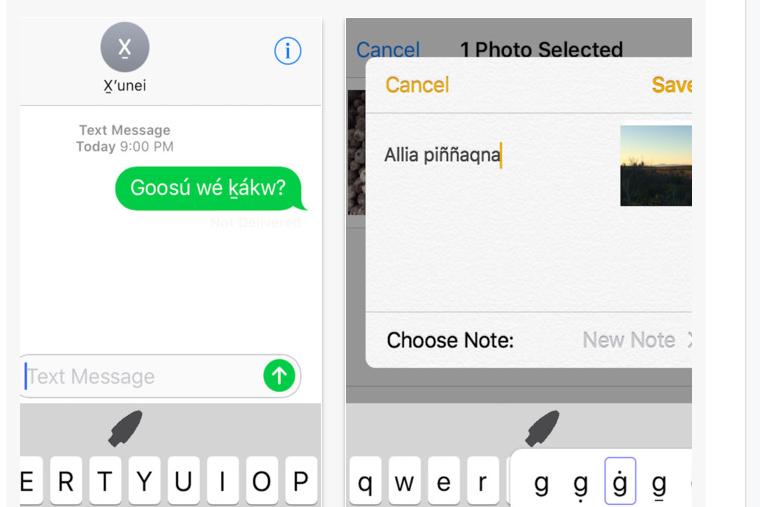

Reid and Grant Magdanz launched an iPhone app last week called Chert. It allows you to add a keyboard to your iPhone — like the extra keyboard for emojis — to type and text in all 20 Alaska Native languages.

The brothers, who are both from Kotzebue but not Alaska Natives themselves, hope that by making the languages more commonplace — something people can more easily integrate into texting, Snapchat, Facebook and across social media — they can revitalize a key piece of Alaska Native culture.

“It’s hard for people to use these languages every day because so much of their day is in the electronic world,” said 22-year-old Grant Magdanz. “Growing up in a place where people are trying to revitalize the language … you just kind of see that there’s a need for it.”

Using the keyboard, you’ll find characters with markers that aren’t used in English. That means you can write phrases like niġisuktuŋa (“I want to eat,” in Inupiaq), or gút ax̱ jeewú (“I have a dime,” in Tlingit).

Reid Magdanz, 26, said he’d noticed people finding characters used in Alaska Native languages online, emailing them to themselves and then copying and saving them to their smartphones to use in the future. Chert provides a much simpler system.

In all, the keyboard has 19 options. Yupigestun, also known as St. Lawrence Island Yupik, isn’t listed because all the characters it uses are available on a standard English keyboard, according to the app. Some of the languages are spoken much more widely than others.

The project builds on another app the team released in January, called Achagat, which provided only an Inupiaq keyboard.

“Achagat” is the word for the Inupiaq alphabet, while “chert” is an English word for flint-like rock, “a type of stone that arrowheads and spear points were traditionally made of,” Reid said.

After the brothers saw a good response to Achagat, they decided to expand to other languages. Grant said he noticed that people who downloaded it used the keyboard consistently, rather than “just downloading and playing with it a bit and not using it.”

They also hope to launch a version of the keyboard for Android phones.

Grant lives in San Francisco and works as a software engineer at a company called Delphix. Reid is an aide for Rep. Jonathan Kreiss-Tomkins, D-Sitka, and works on legislative issues about Alaska Native language revitalization and preservation.

“If you want a language to survive, it has to be used,” said Siri Tuttle, a professor of linguistics at the Alaska Native Language Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

“The fact is that most of the people who are fluent in Alaska Native languages now are older, and most people in Alaska grow up speaking English,” Tuttle said. “The creation of the app is a kind of political act for the languages, in a positive form. Language is very much tied to politics.”

Reid pointed to the suppression of Alaska Native languages as a piece of the state’s history. One example is schools in Alaska that taught only English and forbade students from speaking their native languages, punishing those who did. That’s noted in University of Alaska papers looking at the history of schooling for Alaska Native people.

The act of discouraging people from speaking in their native languages was “depressingly and terribly effective at breaking the chain of language transmission” between generations, Reid said.

“The new generation is coming of age at a time when these traumatic memories of language suppression are more distant,” he said. “That’s what I see happening.”

One recent example of reclamation of Alaska Native language is the northern community of Barrow officially reverting to its old name: Utqiagvik. That change goes into effect Dec. 1.

Grant said he hopes Chert is a way to help fuel the revitalization of such languages.

“At least how I feel is that it can be difficult to find ways to help, as someone who is not Alaska Native,” he said, “and I think the best way to do it, if others are interested, is centering Alaska Native voices and being more in a supporting role.”