Understanding climate change is key to Arctic diplomacy, experts say

Science can help predict where the region is heading. But scientists are finding it harder than ever to forecast changes.

Arctic diplomacy requires a deep understanding of climate change, researchers say — but scientists are struggling to predict and convey the unprecedented changes taking place in the region.

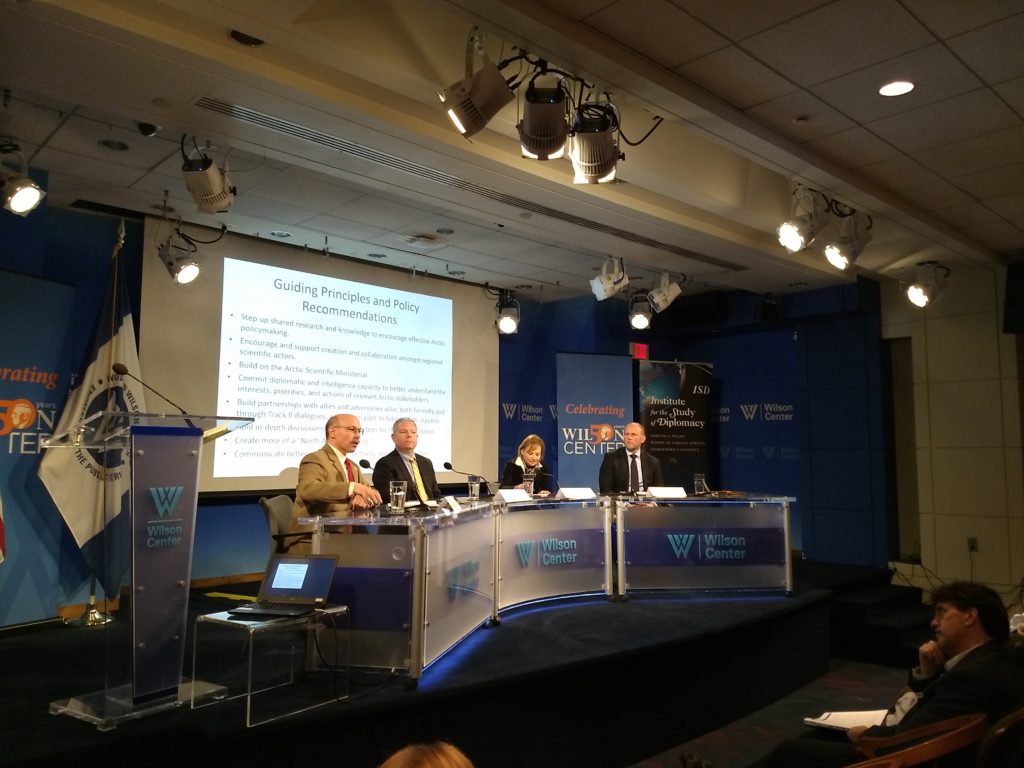

The Institute for the Study of Diplomacy at Georgetown University recently released a report highlighting potential challenges to diplomacy in the circumpolar North. “The New Arctic: Navigating the Realities, Possibilities, and Problems” was created with input from a working group of Arctic experts, scientists, senior policymakers, practitioners and academics.

“Irrefutable changes brought about by rapid warming — more rapid than anticipated and more rapid than elsewhere on the planet — probably cannot be reversed and may not be able to be slowed,” writes Barbara K. Bodine, director of the institute.

These environmental changes are opening up the region to social, cultural, economic changes, such as new shipping routes and better access to natural resources. And those changes can bring geopolitical changes as well.

“There may be new security challenges from Arctic as well as non-Arctic states,” the report’s authors write.

The report encouraged typical diplomatic activities, from building partnerships with both allies and adversaries to conducting in-depth discussions on governance, including the role of the Arctic Council.

But again and again, the authors returned to one of the core reasons the Arctic is changing so rapidly: the environment.

Diplomacy in the Arctic, the authors stressed, will depend upon detailed and accurate scientific research. Science, especially concerning climate change, will help international actors understand the region’s future.

At the Woodrow Wilson Center launch of the report, several of its authors discussed the role of climate change in diplomacy.

Bodine called the changes in the Arctic “an opportunity to practice how to work together — how to get the scientists and the policymakers to find a common language.”

Kelly McFarland, director of programs and research at the institute, said that policymakers need to understand science better, and scientists in turn need to understand exactly how policies can be made.

“Science and policy have a hard time talking to each other at times,” McFarland said. “As much as we can, to bring those two together is a big issue as well.”

Jeremy T. Mathis, an adjunct professor of environmental policy at Georgetown University, spoke to the difficulty of communicating the rapid and unparalleled changes happening in the Arctic. For example, the Bering Sea saw historically low levels of ice in winter 2018.

“We said: 2018, it’s a banner year, it’s radical, unprecedented; never seen anything before like this,” Mathis said. “And then 2019 came along and said ‘here, hold my beer, I’ve got one better for you.’” Sea ice fared even worse in 2019, with melt extending up into the Chukchi Sea, Mathis said.

As scientists watch historic changes unfold, he said, they’re finding it difficult to convey how enormous the transformation is.

“We’re losing our ability to communicate just how much the environment is changing, because we’ve just run out of adjectives to describe it,” he said.

As change becomes the new normal, scientists need to get out of the habit of highlighting change itself, he said. Instead, he proposed focusing more specifically on communicating differences in what he called “societal benefit areas”: disaster preparedness, environmental quality, food security, human health, infrastructure and operations, marine and coastal planning, natural resources, resilient communities, sociocultural services, and weather and climate.

By zeroing in on specific areas and how these changes will affect them, he said, it is easier to track the effects of the change — and to begin moving the ball forward.

“These are places where we can make visible, tangible progress,” Mathis said.

Part of the problem, though, is that environmental change in the Arctic has entered new and unpredictable territory.

“We don’t actually know, scientifically, what it’s going to be like in five years, or three years even, or ten years,” McFarland said. “So in many instances it’s hard to make policy recommendations when you don’t have the hard science on what it’s going to look like or what’s going to be happening.”

But the more we can learn, the better, he said, arguing that more science-based policies will be key to maintaining a conflict-free Arctic.