US Defense Department announces new Arctic security center

The department is still weighing potential locations for the new center.

The U.S. Department of Defense formally announced on Wednesday the establishment of a new regional security studies center for the Arctic.

The Ted Stevens Center for Arctic Security Studies, named for the late Alaska senator, is the sixth regional defense center and the first focused on the Arctic.

The center aims to foster collaboration on security matters across the north, creating an international network of leaders and academics.

Other regional centers focus on security in Europe, Africa and Asia.

This year’s defense authorization act created the center. Senators Lisa Murkowski and Dan Sullivan, both Republicans from Alaska, sponsored the legislation in the Senate and Representative Don Young, also a Republican from Alaska, supported it in the House. Alaska state legislators have voiced support for the center, too.

Murkowski, who first conceived of the idea, pushed for $10 million in funding in the 2021 budget.

The Defense Department is still weighing potential locations. Three existing regional centers are located in Washington, D.C., while two others are located in Germany and Hawaii.

Murkowski has strongly advocated for the center to be located in Alaska, and the University of Alaska has recommended that the defense department set aside $6.5 million to house the center in the university system.

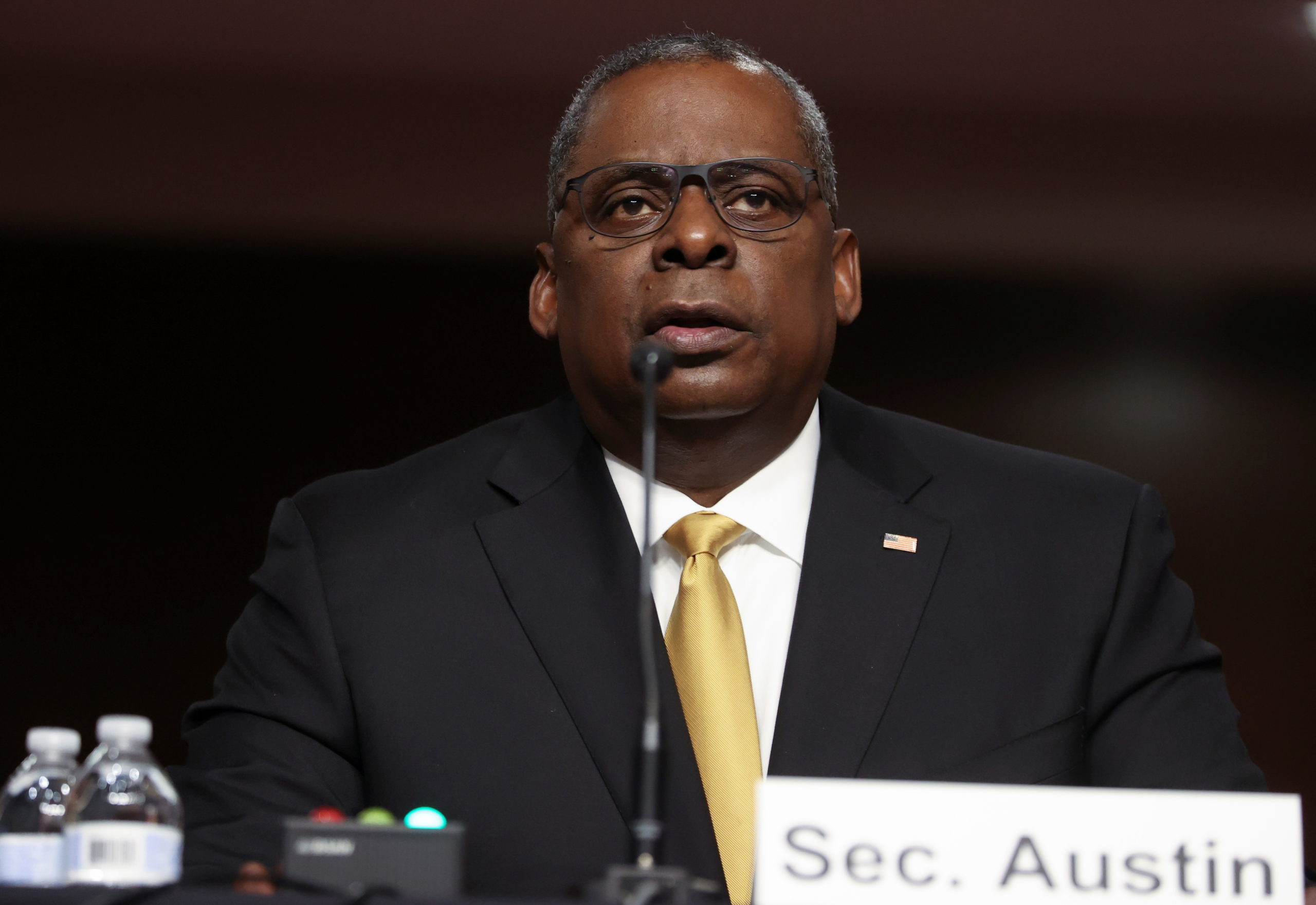

Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III said in a statement on Wednesday that the center will help defense agencies and international partners “pool our collective strength and advance shared interests,” particularly in maintaining rules-based order in the Arctic and addressing the growing threat of climate change.

In a December 2020 statement after the defense authorization legislation passed, Sullivan said the center would provide “desperately needed” Arctic policy expertise within the defense department. It would also help different defense agencies and commands coordinate their Arctic work in order to operate more efficiently and proactively.

The center could be a soft power tool to address security concerns and diplomacy in the north, Murkowski said.

“Given the growing importance of the Arctic in global geopolitical and strategic affairs, the Stevens Center will provide DoD a place to foster the research and dialogue critical to national security especially as it pertains to the Arctic region,” she said in a statement.

Murkowski has long called for such a center, first introducing a bill to establish it in 2019.

In October 2020, she spoke about rising geopolitical tensions at a virtual session of the Arctic Circle Assembly. Without a security studies center focused specifically on the Arctic, she said, “it is one-quarter of the globe that we’re basically overlooking.”

The center could support dialogue among Arctic military leaders, including Russia, Murkowski said.

The Arctic Council has been an example of successful circumpolar collaboration, but its charter excludes discussions of security issues. Murkowski sees the new center as a possible venue for such issues, she said. “It’s one of the reasons that we are helping to establish this.”

At the Arctic Council ministerial meeting in May, Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov called for renewed meetings between Arctic military leaders.

“It is important to extend the positive relations that we have within the Arctic Council to encompass the military sphere as well,” Lavrov said in Reykjavik.

The chiefs of Arctic armed forces once convened annually, but those meetings were halted in 2014 after Russia annexed Crimea. Moving to a different international security forum could allow critical conversations to resume among military leaders.

The new center could also expand beyond traditional military security issues to encompass economic, environmental, and food security — what Murkowski called a “holistic view and understanding of security within this region.”

The focus on climate change in the establishment of the center is significant, said Marisol Maddox, an Arctic analyst at the Wilson Center’s Polar Institute, because it “has tremendous potential to be destabilizing” — from thawing permafrost that damages military installations to growing food insecurity to sea ice melt opening up the region to more maritime activity.

The establishment of the center is an important step toward “coordinating the different partners that we need to be engaging for the traditional security threats but also the non-traditional security threats,” Maddox said.

But it will take time to get the center up and running. In the meantime, leaders can repurpose existing forms such as the Arctic security roundtable at the Munich Security Conference to hold much-needed military discussions, Maddox said.

“We need to be acting faster, because we’re seeing increases in exercises that are increasingly aggressive,” Maddox said.

“We definitely need to have better communication, because the risk level has gotten too high just in the last couple of years,” she said.