US has ‘vital national interests’ at stake in Russia-China relationship in the Arctic, expert says

China and Russia have a complex — and divergent — relationship in the Arctic, says Rebecca Pincus, and the U.S. needs to pay attention.

China and Russia have a complicated relationship in the Arctic, and the details of that relationship will be important to the United States.

That’s according to Rebecca Pincus, an assistant professor at the U.S. Naval War College, who testified last month before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission.

In her testimony, Pincus highlighted China’s and Russia’s different goals in the region.

“Chinese and Russian interests in the Arctic overlap rather than align,” she said. For China, Russia is a means for economic growth; for Russia, China is a way to counter the Western strategy of isolation.

“As a result, there appears to be more to this relationship on paper, and in rhetoric, than in actual investment thus far,” Pincus explained. “While some deals have been struck, other negotiations have broken down over differences between Chinese and Russian visions for their relationship in the Arctic.”

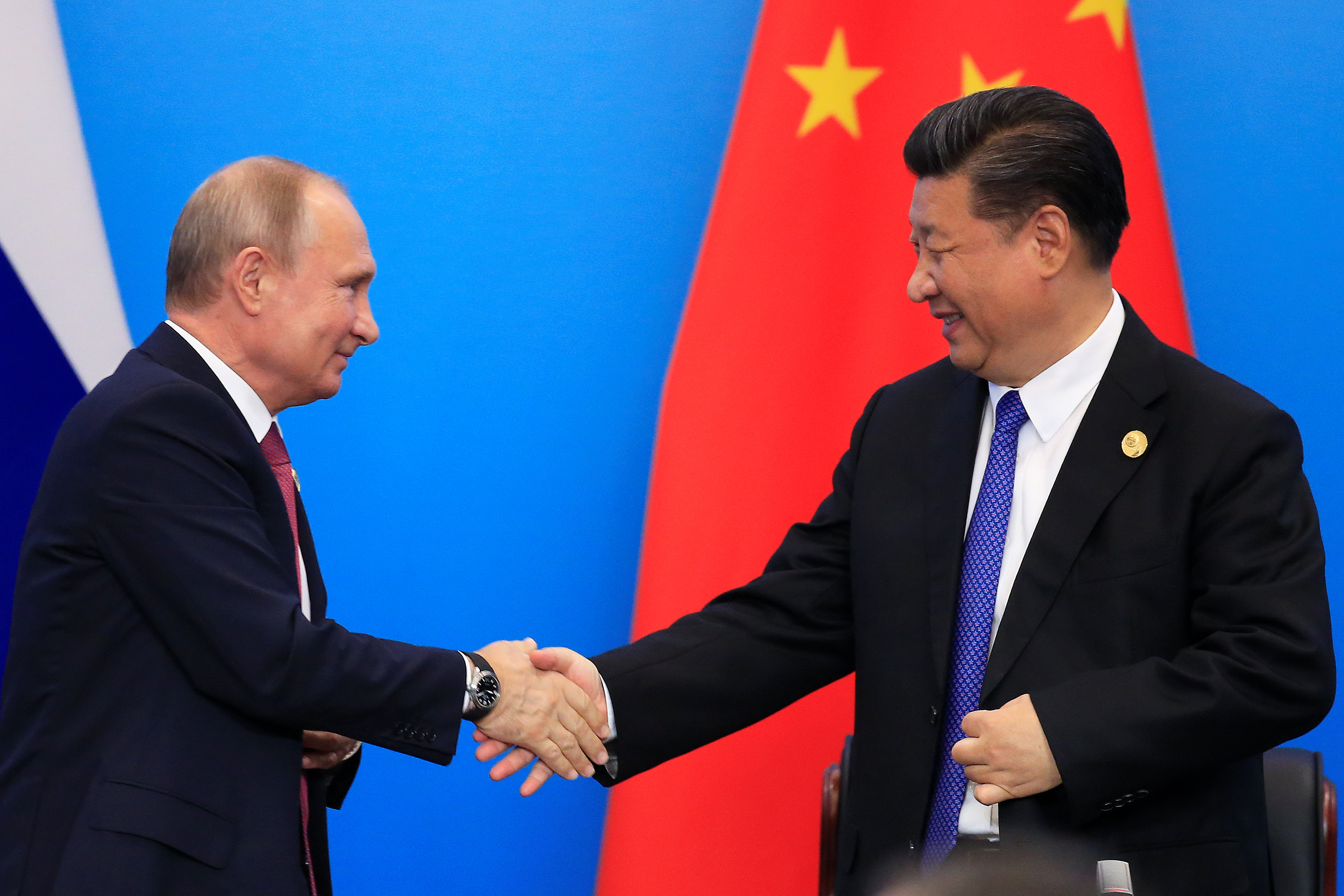

China’s Belt and Road initiative has been a key program for Chinese President Xi Jinping, while the Arctic is a top priority for Russian President Vladimir Putin. The combination of these two areas of focus into the Polar Silk Road is significant, Pincus said, and has the potential to advance both countries’ national goals.

“Will Russia grant China preferential access to the Northern Sea Route?,” for example, Pincus asked. “And what role will China play in the infrastructure that is needed to develop the NSR?”

Yet despite high-level agreement on Arctic collaboration between the two nations, problems are popping up at the bureaucratic level of implementing the initiative, “where the rubber meets the road,” she said. “Thus far, we have not seen a special relationship develop.”

Militarily, a key question is the extent to which Russia will facilitate China’s entry into the Arctic subsurface, Pincus said. While Russia has provided China with some weaponry and expertise, it has been wary of transferring high-end technologies.

Yet Chinese submarines may cruise the Arctic in the next decade, she said, and that could cause tension in China-Russia relations.

“If a Chinese submarine surfaces in the Arctic in the next — it’s probably going to be more like five to 10 years — that’s really going to change the game up there,” she said. “For Russia, that will be a real new environment and introduce new concerns for them.”

Politically, China is building relationships with all eight Arctic states in order to increase its influence over decisions about the future of the region, Pincus said.

“Russia is less vulnerable because it is the Arctic superpower. However, the Russian economy is underdeveloped and brittle, and therefore that acts as a constraint on Moscow’s freedom of action,” she said. “Any sort of turmoil inside Russia will be directly linked to Arctic governance, in a way that I think will be really challenging.”

The U.S. is involved in that governance through its participation in the Arctic Council, and its role in establishing the Arctic Coast Guard Forum as an important space for NATO allies and Russia to collaborate.

But the U.S. also has interests simply because it has territory in the Arctic — something commissioners seemed not to be fully aware of at first.

Commissioner Kenneth Lewis asked, “What role do we have, and how do we pursue our role, since we’re not a—we have no land in the Arctic?” He was quickly corrected by his colleagues, adding, “I’m sorry, yes—in Alaska.”

Robin Cleveland, vice chair of the committee, said that she was also planning to ask about U.S. interests in the Arctic. “I’m glad to know we have vested interests,” she said. “Because it sort of eludes me in terms of distance.”

An important next step for the U.S. to advance its interests in the Arctic, Pincus said, would be to fully fund the U.S. Coast Guard’s icebreaker program.

“Without visible surface presence exercised in the region, and year-round all-access capability, the U.S. will remain at a disadvantage,” she said.

Pincus also recommended stepped-up international cooperation in the region.

“It is important to shore up relations with our Nordic allies in the region, as well as Canada, to build a common consensus and dialogue on China in the Arctic,” she said.

“We need to play a shaping role in this region. It’s our backyard. We have vital national interests at stake,” Pincus said.