Using old weather to inform Arctic climate change work today

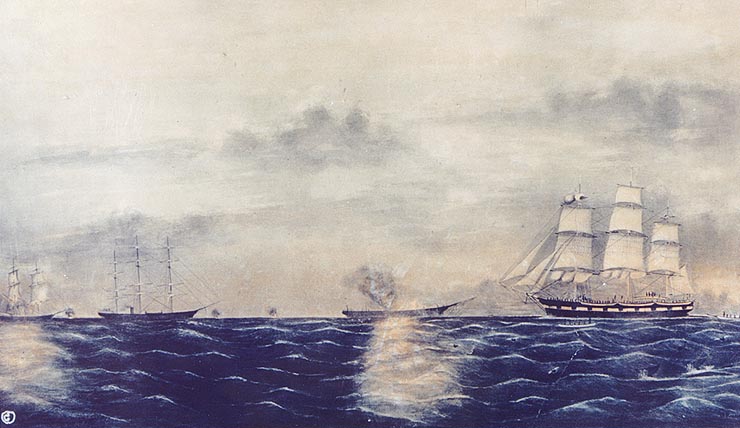

November 26, 1863. A whaling vessel named Milo catches the wind of a chilled morning in New Bedford, Massachusetts, and heads north toward the hazardous waters of the Bering Sea. At the helm is Master John Capen Hawes, whose keen eye is not just on the lookout for whales, but a far more dangerous adversary: the CSS Shenandoah. A fearsome Confederate cruiser, Shenandoah had become well-known for destroying many Union whale ships and merchant vessels during the course of the American Civil War.

And for good reason. Two years after its November launch, the Milo was captured in the Bering Sea by Shenandoah and ransomed to take prisoners from the whale ship to San Francisco. The Milo was eventually sold out in 1872 and John Capen Hawes would go down in American history as the first person to give the whereabouts of the Shenandoah to the world, warning other Union ships of its destruction.

One hundred and fifty years later, what may have been a long-forgotten lesser story in the great saga of America’s bloody battle for a freer union is now being used to understand a rapidly changing climate in the Arctic.

Old weather

The Milo’s logbook of its 1863 voyage is just one of 35 whaling logs that are part of the Old Weather: Whaling project, an online portal that allows volunteers to assist in exploring, marking and transcribing ship logs, largely from the 19th and early 20th centuries. The initiative, and its sister site Old Weather, were founded by Dr. Philip Brohan at the UK Met Office in 2010 to recover historical marine-meteorological observations that can be used by supercomputers to reconstruct the weather of the past 150 years. Historic ship logs are difficult for computers to transcribe and mark because of their diverse and idiosyncratic handwriting that only humans can read and understand effectively.

Despite their difficulty, ship loggers’ observations on sea ice conditions that whaling ships have sailed through and documented while navigating Arctic waters are vital to informing the foundations of climate science research being done today.

“Old Weather volunteers have recovered millions of new-to-science weather observations,” explains Kevin Wood, a research scientist at the University of Washington’s Joint Institute for the Study of Atmosphere and the Arctic Lead Investigator for Old Weather.

“For the Arctic, they have also been recovering many thousands of sea-ice observations and other environmental data — the former specifically to validate century-scale sea-ice model hindcast experiments, so we can better know well our models are working, and more fundamentally document what the Arctic sea ice was like in the past (especially in offshore areas and in some instances in winter).”

Engaging citizens in recovering underutilized data

At a time when science is being rhetorically and financially devalued by the Trump administration in the United States, as covered in an earlier article on the Alaska Sea Grant program, the work done by Old Weather is important both for the data being recovered and for engaging non-scientists in advancing research across multiple fields.

“Access to historical data is essential for understanding both past and current events, especially in the ocean domain where important geospatial, environmental and social/cultural data are found only in manuscript formats inaccessible to computers,” says Wood. “Common barriers constrain the effective use of these data in any discipline: severely limited access to unique physical records; the need to transform large quantities of manuscript data into formats that can be collated and analyzed by computers; and the need for advanced computing technologies required to carry out sophisticated analyses.”

Old Weather focuses on historical U.S. naval logbooks currently because they provide one of the most significant underutilized data records in the world. But Wood isn’t stopping there.

“With the additional capabilities of the collaborating institutions we integrate these data into national research databases where they will be available for many kinds of research and scholarship. For example, these data will be assimilated by high-performance atmosphere-ocean retrospective analysis (reanalysis) systems in the United States and Europe; these are capable of reconstructing the state of the weather at six-hour intervals for the past 150 years or more, plot every ship and station in the world that has reported data on a map, and describe environmental conditions at an individual ship or station up to ocean basin and hemispheric scales. For example, see the animations in these Old Weather blog posts: All will be assimilated and Too windy for Zeppelins.”

And although Old Weather has only worked with UK and U.S. logs, the project has begun collaborations with the Northern Seas Project and AINA on Canadian Logs, along with a side project on logs of the Russian-American company in Alaska.

More to do

With 19 completed classifications and 364 classifications in progress, the logbook from the Milo is only 4 percent complete. With thousands of pages to mark and transcribe, there is a lot for citizen scientists to do in the years to come.

But every little bit counts. And the results of Old Weather are more important now than ever before. “Once completed, we may have a much better understanding of extreme weather, rapid sea-ice loss and Arctic change, and other global weather and climate phenomena that require long baseline data to study.”