The Week Ahead: It’s our back yard

The approval of Greenland’s third World Heritage Site shows that the areas that host them are aware of their value. That may put them at odds with conservationists who place a different sort of value on the designation.

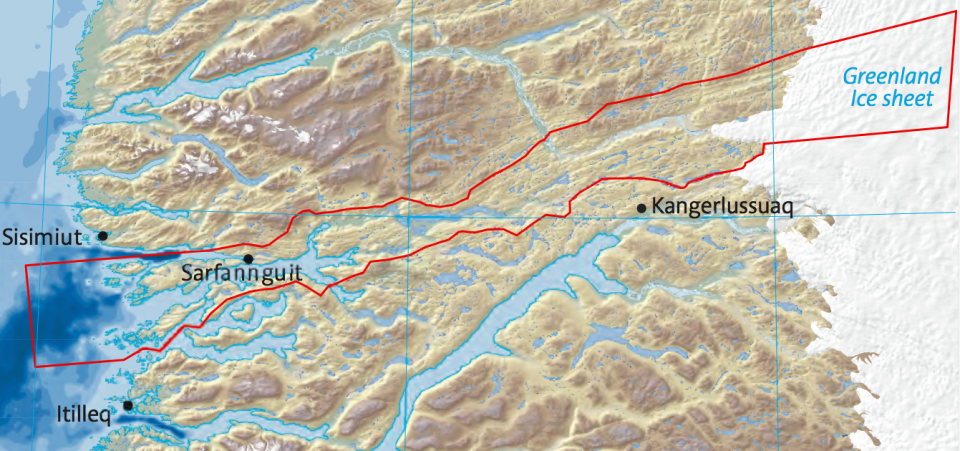

A third Greenlandic site — Aasivissuit-Nipisat, an area nicknamed “the Inuit hunting ground between sea and ice” — was added to the list of UN-approved World Heritage Sites on Saturday.

Getting included on the list is an arduous task, requiring time and resources — to the point that critics of the system suggest poorer countries are prevented from applying. As evidence, they point to a severe overweight of European and North American sites, which have half of the 1,000 or so that have been approved.

There is also a commitment involved: World Heritage Sites may be used for non-conservation purposes (which is important to note in the Aasivissuit-Nipisat discussion, since Greenland’s first inter-municipality road has long been mulled for precisely this area), but they can be stripped of their status if the World Heritage Committee, which meets once a year to review the list and add new members, determines that they are not properly managed or protected.

This has only happened twice, but more than 50 sites are in the danger zone for various reasons. For example, concern about the encroachment of oil exploration on Wrangel Island, in the Russian Arctic, may see it added to this list.

Still, for many a lawmaker, the prestige that comes with being added to the list is worth the cost: Sites are only approved if they are deemed important to the “collective interests of humanity.” This designation is as momentous as it sounds, as reactions to approvals suggest.

Malik Berthelsen, the mayor of Qeqqata, the district where Aasivissuit-Nipisat is located, described being chosen as important to the self-confidence of the region, the country and the Arctic. It would also make the area known to the outside world, too, he said.

This last is as big a motivation as any to seek approval: Having the UN’s cultural imprimatur can reinforce an existing tourism profile (as with Greenland’s Ilulissat Icefjord, which was inscribed — as it’s called in the UNESCO jargon — in 2004) or serve as the cornerstone for a new tourism profile (for example, the Kujataa, a sub-Arctic landscape that was farmed by Inuit and Norse settlers, inscribed in 2017).

[Amid environmental fears, UNESCO makes first ever mission to Russia’s remote Wrangel Island]

As many as three dozen new sites are inscribed each year based on the nominations of UN members, who put forward sites in their own states (in the case of Greenland, Denmark officially submits the nominations it is asked to). While this ensures that national sovereignty extends to cultural affairs, it is not a bulwark against outside groups seeking to play a role. In 2017, for example, a report, penned by conservation groups together with the World Heritage Center, identified seven maritime areas in the Arctic that should be considered for inclusion as World Heritage Sites.

Their argument for stating their opinion is that while the Arctic as a whole now has six World Heritage sites, only Wrangel Island is a maritime site. A similar situation, they point out, exists when it comes to other forms of recognition.

Their message to the Arctic states that would be responsible for nominating the sites is that adding them to the list would protect them from the twin pressures of a changing climate and economic activity. This, the group says, falls into one of two categories: long-standing cultural and traditional uses that may, in fact, be a form of nature conservation (the acceptable sort) and new activity, like shipping and resource extraction (which they’d rather not see).

Tourism is not mentioned, but the group notes that the more remote a site is, the more likely it is that its conservation status will yield results. Areas hosting newly minted heritage-sites are unlikely to agree.

The Arctic in time of Trump

Also this week, America celebrates Independence Day on July 4. How is the Arctic fairing the time of Trump?

Arctic Today correspondent Melanie Schreiber suggests in a recent article that growing security concerns are making the Arctic loom larger in Washington. As the Arctic opens to more economic activity — and countries like Russia and China seek to fill the void — U.S. officials have started to worry about the nation’s lack of preparedness.

The Week Ahead is a preview of some of the events related to the region that will be in the news in the coming week. If you have a topic you think ought to be profiled in a coming week, please email ne**@ar*********.com.