The Week Ahead: Better-educated guesses

Weather forecasts in the Arctic aren't as accurate as those further south. But there are gathering incentives to change that.

If you knew earlier in the week what the weather was going to be like today, it’s likely because you had consulted a weather forecast. At lower latitudes, forecasts of this sort, telling us (more or less) what the weather will probably be like days in advance, are taken for granted. Head further north, however, and the amount of time in advance meteorologists can make accurate forecasts declines rapidly.

This is because weather forecasts depend on the quality and the quantity of the information used to make what, essentially, are educated guesses about how a weather systems will develop. This takes good observations about weather patterns that are moving towards a given location. But to make good use of those measurements, meteorologists need to understand how the patterns they observe can be expected to act.

Getting good data requires a constant flow of information about atmospheric conditions. Knowing what it will do requires a historical knowledge of how past weather events have developed. Compared with more populated parts of the globe, both are lacking in the North.

Yet, as the polar regions warm, the importance of improving forecasting grows and thus the pressure to make better forecasts. In addition to benefiting the people who live in the region — who are increasingly no longer able to rely on traditional knowledge of how the weather will act — this will benefit commercial activity in the region, which will require things like accurate, up-to-the minute predictions of weather and sea ice conditions, as well as seasonal outlooks.

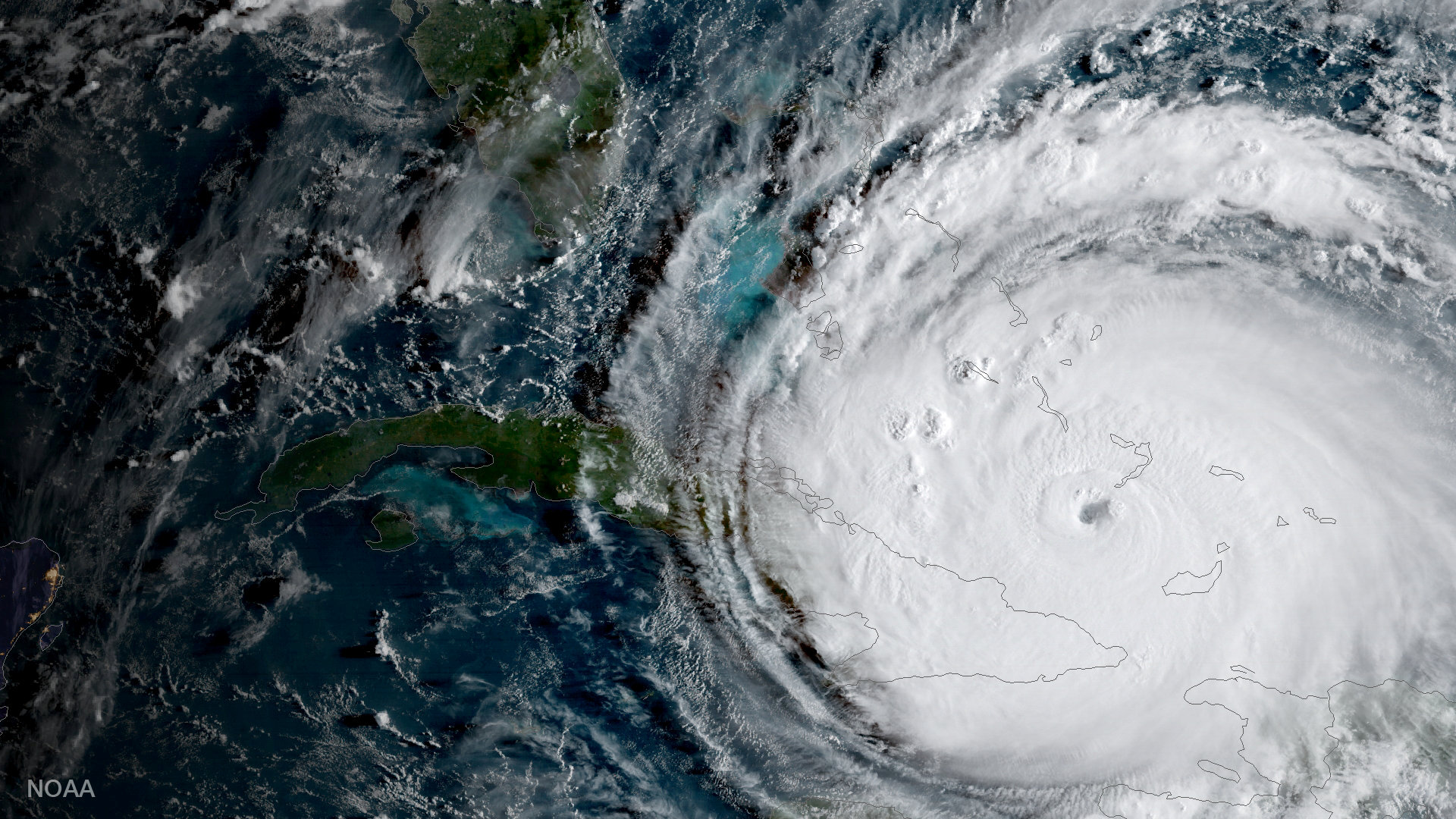

[Continuous satellite coverage in the Arctic could help predict extreme weather around the globe]

Add to that an increasing understanding of the connection between weather in the polar regions with weather elsewhere and it becomes clear that better polar weather prediction could mean better forecasting for hundreds of millions of people outside the region as well.

Although the science is not yet proven, it is believed that warming Arctic air masses and declining sea ice affect ocean circulation and the jet stream. In the Northern Hemisphere, this might give rise to extreme weather events such as winter cold snaps, summer heat waves and droughts. Other studies suggest there is a connection to the way hurricanes and even tornadoes behave.

The importance of good weather forecasting in the Arctic has not escaped the Arctic Council, which, during the Finnish chairmanship, has made it one of four focus areas. Likewise, the World Meteorological Organization, is hoping that its ‘special observing period’, which ends on September 30, will give scientists a better handle on the region’s weather.

[In Alaska, the National Weather Service must change as rapidly as the climate]

The WMO has used the two-month campaign, carried out in connection its Year of Polar Prediction (which, despite its name, spans from May 2017 to May 2019), to facilitate observations that, in other parts of the world, are considered routine: launching weather-balloons, setting up meteorological stations and tracking weather events from the air and from space.

A key element of the WMO-led 10-year Polar Prediction Project, which concludes in 2022, the special observation period was intended as an opportunity for meteorologists to gather as many observations from the region as possible. Once collated and processed, they should lead to more precise predictions of what the weather will be like. That is a welcome outlook at any latitude.

Déjà vote

Lawmakers in Greenland preparing for the opening of Inatsisartut, the national assembly, on September 28, will have seen some of the weightiest issues on the legislative docket before, including a much-delayed fisheries reform and airport construction (though, if passed, this bill would likely be the last of a series of incremental legislation relating to the project).

Further discussion of whether to place an official representative in Beijing may also come up on November 12, during the foreign minister’s presentation of the government’s foreign-policy priorities.

Perhaps most likely to give legislators a sense of déjà vu, however, will be a proposal to hold a referendum on whether uranium mining should be permitted.

The matter was resolved 2013, when the assembly overturned a ban that had been in place since 1988. The problem, though, according to IA, the party that has asked Inatsisartut to take up the matter again, is that the measure passed by a single vote.

With no clear political majority, a public that remains evenly divided on the matter and an ongoing debate, the two camps are more entrenched than they were before the 2013 vote, IA says.

Meanwhile, a project in southern Greenland involving uranium mining is preparing to ask for final approval to begin operation. The dispute there shows why the topic is so hotly contested: Those that live near the site of the proposed mine are asking it to be rejected, out fear that the dust it kicks up will render their town uninhabitable. Backers warn that anything less than wholehearted backing will do irreparable harm to a nascent mining industry.

In asking Inatsisartut to turn the vote over to the people, IA points to a 2014 poll finding that 71 percent of voters, regardless of how they felt about the issue, were in favor of a referendum. For IA, asking voters to decide could prove a popular way to duck a potentially unpopular decision.

Arctic connections

On September 26 and 27, the Arctic Council’s Task Force on Improved Connectivity in the Arctic gathers in Copenhagen.

Established in 2017, and based on the work of the Task Force on Telecommunications Infrastructure in the Arctic, which existed between 2015 and 2017, the TFICA, is responsible for comparing the region’s telecommunications needs with available infrastructure technologies, and, to the extent possible, projected technological and commercial developments that might change how feasible it is to connect remote communities.

The task force also works with the telecommunications industry and the Arctic Economic Council to encourage the creation of required infrastructure. One way to do this is through subsidies; another would be to partner with commercial operations, such as mines, to ensure that their local networks extend to nearby communities.

Another proposal is to convince companies to use the Arctic as a proving ground for technologies that could be rolled out in other remote areas. If successful, these firms can claim that if they can make the connection to the Arctic, then they can make it anywhere.

Read more about the work of the TFICA to date

The Week Ahead is a preview of some of the events related to the region that will be in the news in the coming week. If you have a topic you think ought to be profiled in a coming week, please email ne**@ar*********.com.