The Week Ahead: Bringing the Arctic to the internet

A new approach might help pick up the agonizingly slow pace of bringing fast internet to the North.

In 2016, the Arctic Economic Council held its first Arctic Broadband Summit amid frustration that, despite all the talk about pokey internet speeds in the North, little was being done about it.

Bringing together policy makers and industry representatives in Utqiaġvik (then known as Barrow), Alaska, was intended to give those who make decisions about telecoms the full Arctic internet experience, and in so doing get them to understand what it means to be cut off from its opportunities.

On June 27 and 28, the AEC holds its third internet summit. Like the Utqiaġvik meeting, and last year’s gathering in Oulu, Finland, the 2018 edition is billed as a ‘Top of the World’ summit, but this year the organizers will instead be bringing the Arctic to the decision-makers.

[Regional differences complicate efforts to bring broadband to the Arctic]

Holding the summit in Sapporo, in far northern Japan, emphasizes the Arctic as a region of commercial opportunity, says Tero Vauraste, the managing director of Arctia, a Finnish firm that operates icebreakers, and the current chair of the AEC.

“We’ve seen that there is growing international interest in the Arctic,” Vauraste said. “This is us showing that the Arctic is interested in them, too. The Arctic is not a closed club.”

Getting internet firms to go from interested to investors, though, will require that they are convinced there is profit to be made.

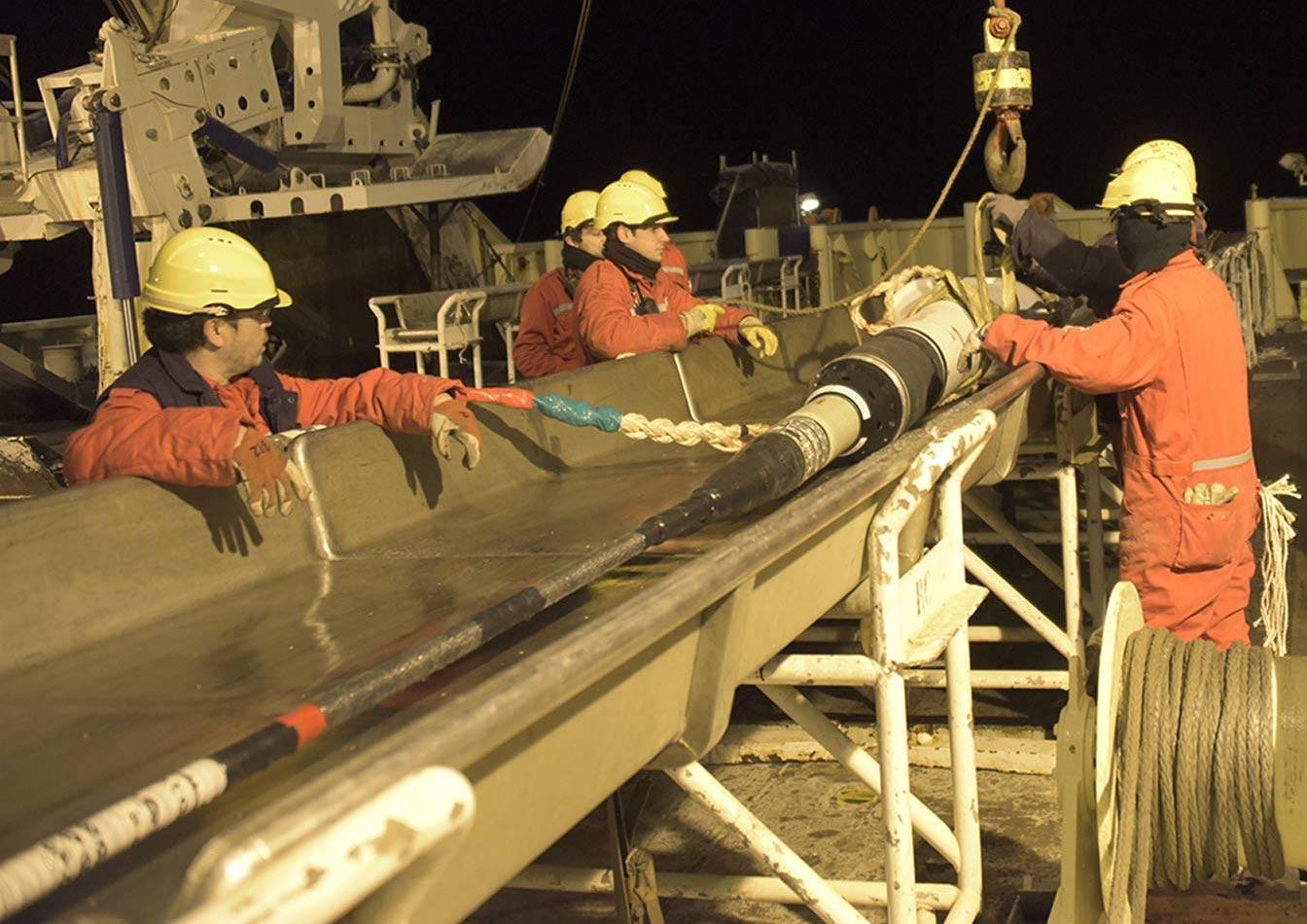

One sales pitch they will hear is that — just as it does for shipping physical goods — the Arctic can offer a shorter route for data to travel between population centers. This is something Quintillion, an Anchorage-based firm, is already taking advantage of by laying a fiber optic cable that eventually aims to link Japan with London via the Northwest Passages.

For the communities it passes, this could be like suddenly having an interstate passing by where once there was a footpath. There is no guarantee they will end up with on-ramps to that interstate, but Vauraste reckons that, once the infrastructure is there, it will make it easier for firms to take advantage of the Arctic’s other selling point: cold temperatures that can cool the computers that store their information.

Placing a data center in a cold climate can reduce power consumption by as much as half, and bring down overall operational costs by a tenth. This is something well connected cold-climate countries and big tech firms have already capitalised on. Last week, for example, Microsoft, a software-maker, announced it would build new data centres in Oslo and Stavanger, Norway.

Access to renewables, such as wind in Finland, geothermal in Iceland or hydroelectric in Greenland, sweetens the pot, but increasingly the top of the world is realizing that it needs to give outside firms a good business case if its people are to stop ranking at the bottom in connectivity.

A fine kettle of fish

Mackerel fishing has a brief history in Greenland: The species were first caught in the waters off the island’s eastern coast in 2011. The early results seemed to indicate the fishery would be wondrous: In 2014, 73,000 tons of mackerel, one of the world’s most lucrative fish species, were caught. Their sale value amounted to a quarter of the country’s export earnings that year.

Since then, the results have been disappointing, with catches the past three years falling far short of the total permitted, though this appears to have more to do with poor administration than anything else.

Water temperatures determine when the mackerel season gets underway each year, and it is possible that this week the annual migration will reach far enough north for boats to begin fishing the 66,000 tons they were allotted this year during negotiations with the EU and other North Atlantic countries.

[Greenland moves to join North Atlantic mackerel fishing agreement]

In all, the 20 countries that fish for mackerel are permitted to land 817,000 tons. Although this is about 50 percent more than scientists recommend, bringing the figure down is unlikely. As the mackerel move further north in search of cooler water, new countries — first Iceland, now Greenland — are arguing they have the right to fish for them. Meanwhile, other countries whose claims have become more tenuous as the mackerel have moved away, have shown themselves unwilling to give up their quotas. So tetchy is the situation that when mackerel arrived in Icelandic waters in the late 2000s, the EU and Norway initially refused to recognize Icelandic fishermen’s right to fish for them.

Icelandic studies later showed that the arrival of the mackerel was no fluke; as ocean temperatures had risen, they could now be expected to return each year. Greenland’s own approach was to label its mackerel fishing as “experimental,” allowing it remain outside the negotiation system until it had enough information to base its claim on, while at the same time working out the kinks of its own quota system. Should they succeed, landing their share of mackerel will be an easy task, however briefly it lasts.

The show goes ever on

First staged in 2005, the Alianait arts festival has become Nunavut’s largest event. The festival, most recognisable for the purple and gold big top that houses its main stage, runs this year from June 29 to July 2, but its impact will continue to reverberate after the show comes to a close.

Part cultural institution, Alianait has a year-round presence in the form of the concert series it instituted in 2010. In addition to Iqaluit, performances are held in other Nunavut communities.

Part community movement, Alianait works with schools and other organisations to use art and music to teach cultural skills to young people.

As far as Alianait is concerned, all Nunavut’s a stage, all year round.

The Week Ahead is a preview of some of the events related to the region that will be in the news in the coming week. If you have a topic you think ought to be profiled in a coming week, please email ne**@ar*********.com.