The Week Ahead: Degrees of difference

Even if climate scientists gathered in Poland this week and next can come up with a way keep global warming at bay, an ice-free summer is likely in the Arctic’s future

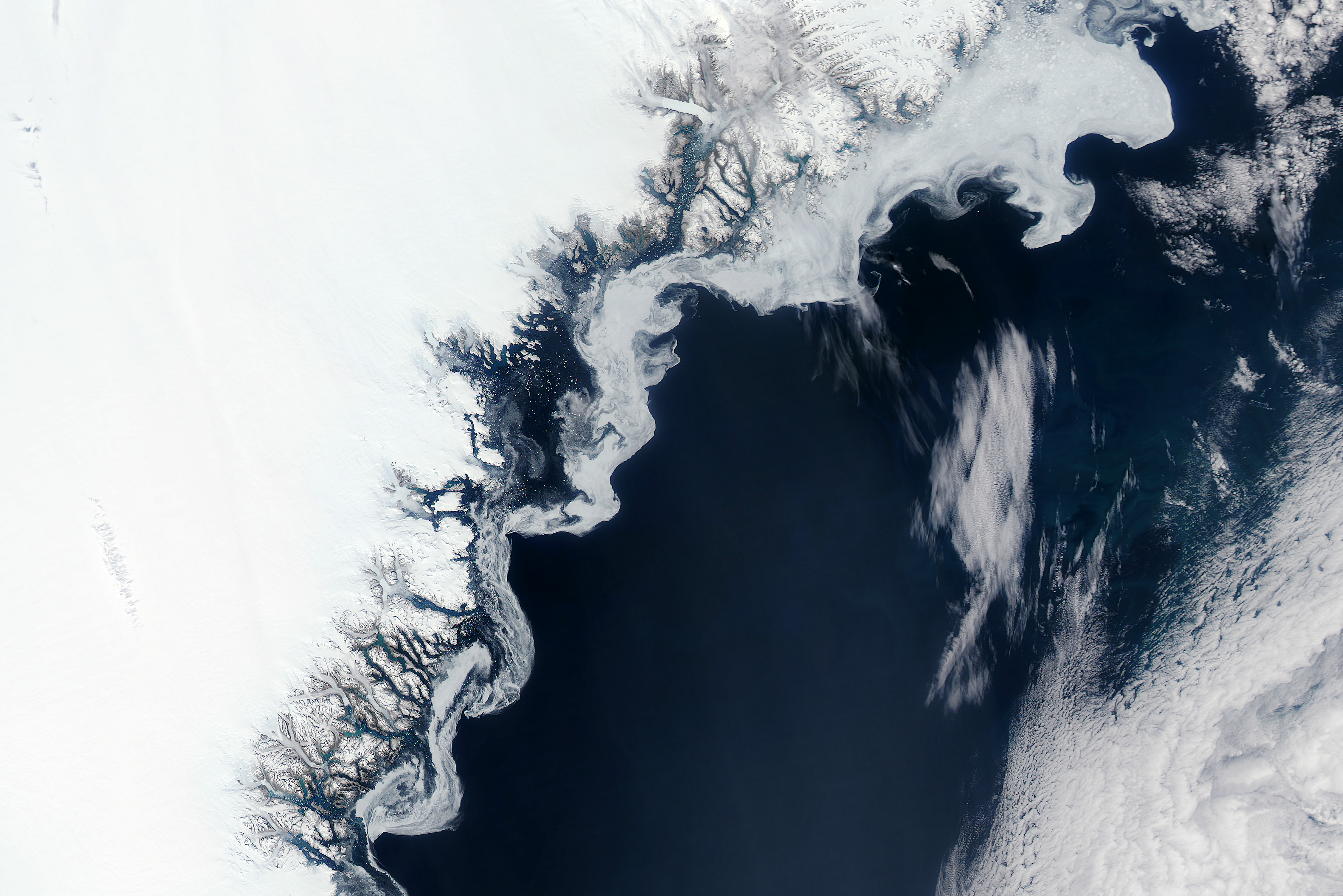

At least once in the next fortnight — although more probably several times — you will hear that temperatures in the Arctic are rising twice as fast as elsewhere on the planet, and that an “ice-free*” summer in the Arctic Ocean can be expected some time before the end of the century, and perhaps as soon as 2040.

The former is a matter of observation and difficult to dispute. The latter, on the other hand, is a matter of interpretation, and previous forecasts for the first Arctic ice-out have proven overly pessimistic.

Still, sea-ice extents are clearly declining: The 12 lowest summer extents have all been recorded during the past 12 years, according to the Colorado-based National Snow and Ice Data Center. And both this fact, as well as the temperature observations, are among the ever-more-numerous examples scientists point to when calling for action to reduce carbon pollution, and to address the problems caused by the warmer temperatures previous pollution has caused.

[Sea ice should be rapidly re-freezing in the Arctic Ocean right now. It’s not]

On Monday, December 3, and for the next two weeks, scientists and others involved with such efforts will gather in Katowice, Poland, for the granddaddy global-warming gathering of them all: the annual U.N. climate conference, which brings together representatives from over 200 countries.

The aim this year is to write the rulebook that will guide the 196 countries that adopted the 2015 Paris Agreement, due to take effect in 2020. This means sorting out things like how to measure carbon pollution (and how to check to make sure that countries aren’t fudging their figures) as well as how to finance the initiatives that will be necessary to reach the agreement’s goal of a maximum 1.5 degrees Celsuis rise in global temperatures, compared with pre-industrial levels.

Previously the target everyone talking about was 2 degrees C. Measured in Arctic terms, the half-degree difference would mean an increase in the likelihood of an ice-free summer from once every 40 years to once every 3-5 years, according to a paper published earlier this year.

Another measure presented in the paper suggests that keeping temperature increases to 1.5 degrees C, rather than 2 degrees C, reduces the chances of an ice-free summer by 2100 from 100 percent to 30 precent. “For warming above 2 degrees C,” according to Alexandra Jahn, one of the authors, “frequent ice-free conditions can be expected, potentially for several months per year.”

Yet, even the 2 degrees C target may prove too hard to hit. Given the current trends (which, in part, saw an increase in carbon pollution in 2018), temperatures are likely to rise by at least 3 degrees C by the end of the century.

Were temperatures to rise that much, ice-free conditions, Jahn’s paper finds, could be expected every year.

The delegates in Katowice will have a lot of topics to address in the coming weeks, but, if Jahn’s various temperature scenarios can be assumed to hold true, then the question of whether they can dispel the possibility of an ice-free Arctic will not be one of them.

*Regardless of which definition you use, “ice-free” doesn’t mean completely devoid of ice. When talking about a single year, “ice-free” typically refers to a minimum September sea-ice extent of less than 1 million square kilometers. When looking at period of several years, “ice-free” typically refers to a minimum extent of less than 1 million square kilometers for at least five consecutive years.

Far East meets High North

Talk Asia and the Arctic, and typically it is China that comes to mind. This week, however, the organizers of Arctic Circle, a big annual gathering in Iceland, will put on their eighth forum not in Beijing or Shanghai, but in Seoul.

As with past forums, the South Korea meeting, being held December 7-8, is a co-organized locally and designed as a way to drum up interest in the Arctic among those unfamiliar with the region. For local businesses and universities, the events provide a platform for showing what they can contribute. A 2017 event, held in Edinburgh, for example, was used to make the case for Scotland taking a greater interest in the region.

South Korea’s foreign ministry, a co-organizer of week’s event, has something similar in mind, though it will likely have an easier time making its arguments than either Edinburgh or even Beijing, which will organize a similar event in 2019.

[For Asian countries, Arctic co-operation reflects regional realities]

Like China, South Korea, was granted observer status with the Arctic Council in 2013, and both have long had an interest in taking advantage of the shorter distance the Northern Sea Route, a shipping lane through the Russian Arctic, offers.

South Korea, though, has the advantage of being able to point hesitant businesses in the direction of the Korea Shipowners’ Association, a lobby group representing some 200 firms, that last year became the first non-Arctic member of the Arctic Economic Council. This suggests to businesses in other industries that there are serious opportunities in the region. It also displays to potential partners in the Arctic that South Korea is willing to involve itself in regional organizations.

Helping its firms get a better toe-hold in the region would also help further Seoul’s aim of using its New Northern Policy, launched as a way to expand economic ties with its nearest neighbors, to push development of the Northern Sea Route and gas reserves in northern Russia. In addition, Seoul has suggested establishing a free-trade area with the Eurasian Economic Union, a Russian-led group of former Soviet republics.

The idea, which is supported by Moon Jae-in, the South Korean president, is promoted as a way to give South Korea a “third route” for economic growth, in addition to its long-standing ties to the U.S. and Japan, and its more recently established connections with China.

Like with much else when it comes to Asia, South Korean interest in the Arctic has been overshadowed by the scramble to understand China’s intentions in the region. That is understandable, but instead of fretting over what Beijing might be getting up to, perhaps more thought should be going to how to encourage Seoul do to more of what it is already doing.

The Week Ahead is a preview of some of the events related to the region that will be in the news in the coming week. If you have a topic you think ought to be profiled in a coming week, please email [email protected].