The Week Ahead: Lands of plenty

In the Arctic, hunger is often the catch of the day. It does not need to be that way.

By far the biggest Arctic event this week is the annual Arctic Circle Assembly in Reykjavík, Iceland, which gets underway on Thursday. ArcticToday will preview that conference separately later this week.

But several other events of importance to the Arctic take place this week, too. Among them is the United Nations’ World Food Day, on October 16. World Food Day — and its cousin, Zero Hunger, one of 17 anti-poverty goals the UN hopes to reach by 2030 – seek to address the problem of malnutrition, first and foremost by addressing shortcomings in the agricultural sector, given its fundamental role in improving the food security the one out of every nine people estimated to be malnourished worldwide.

No single figure exists for malnutrition in the North, but a patchwork of studies suggests a dire situation: A 2012 survey, for example, found that at least 63 percent of Inuit households in the Canadian Arctic were food insecure (a condition defined as lacking reliable access to a sufficient quantity of affordable, nutritious food). This in a country where the national rate was otherwise close to the global average.

Even in places where the figures look promising, a closer analysis reveals deep inequalities — while at the same time suggesting where efforts to address the situation ought to focus. In a 2010 survey of the situation in Qeqertarsuaq, Greenland, the overall food-insecurity was found to be 8 percent. However, amongst women, seniors and those who did not hunt, access to adequate food was considerably lower.

[More than half of Inuit in northern Canada don’t get enough food]

Typically Northern diets are comprised of nutrient-dense animals and plants harvested from the local environment, often referred to as country foods. The more purchased, processed food a diet includes, the less nutrition it tends to provide, while at the same time raising the cost of living. This underscores that, even though a country-food diet is not free (hunting requires time and hunters must pay for things like ammunition and fuel), given an equal amount of money, in the North, it provides more nutrition than one composed primarily of purchased food.

Because there are costs involved, Northern residents who want to be active in the traditional economy need to be a part of the money economy as well. More money to buy food and less time to hunt it has been shown to result in a gradual drift away from country food, though. Some initiatives, such as a recent relaxation of a Greenlandic regulation that prevented hunters and fishermen from selling anything but fresh fish and meat at the country’s open-air food markets, seek to reverse the trend by supporting the establishment of a bigger market country food.

Recent developments have underscored that the region, despite its poor nutrition statistics, should be one of bounty: Earlier this month, representatives from five Arctic states, four major other major fishing countries and the EU, signed an agreement that will delay the start of commercial fishing in the international waters of the Arctic Ocean. One of the goals is to prevent coastal fish stocks, of the sort local fishermen rely on, from being depleted. And, at the more practical level, EALLU, a book produced by indigenous groups, was named the best food-book of the year at the 2018 World Cookbook Awards.

[Food in Greenland: Market economy]

This goodness may be in peril: The report accompanying the Qeqertarsuaq study warned that the changing environment may exacerbate food insecurity for everyone. Others, though, point to the benefits of a warming climate: New fish species follow warming ocean currents, and, on land, cold-hardy crops such as carrots and potatoes can either become new additions to traditional diets, or be grown and sold.

Even in bad years, this can be turned to local growers’ advantage. Greenland’s potato harvest, which got underway at the end of September, is looking to be about 60 tons, half of last year’s total, due to a colder-than-expected growing season. But because the potatoes are harvested will have spent more time in the ground, their quality will likely be higher, and should allow them to fetch a higher price. If life hands you a lemon, the solution, Arctic residents are finding, is to make mashed potatoes.

Hearing. Listening, too?

Also this week, at the Canadian Senate, Natan Obed, president of ITK, which seeks to protect the interests of Canadian Inuit, will provide testimony to its special committee on the Arctic on Monday, October 15.

Obed previously addressed the Senate in January, when he testified before its committee on aboriginal peoples. At that time, he was asked to answer six questions, relating to things like how he envisions the future of the Inuit and their relationship to Ottawa.

This time around, the line of inquiry will stem from the Arctic committee’s mandate “to consider the significant and rapid changes to the Arctic, and impacts on original inhabitants.” In practice, that means speaking with representatives of the country’s northern territories and other parts of the country that play a role in the Arctic, to come up with suggestions for what Ottawa’s priorities for the region should be.

Past witnesses, called since the committee’s first meeting in March, have included a distinguished array of individuals with something to say about the region. During his January appearance, Obed, however, openly aired his doubts what impact talking to lawmakers has.

“The challenge is always that the federal government has its own prerogative on how it makes decisions, on where it invests money, on who it listens to and who it doesn’t.”

By calling Obed in again, senators will have a second chance to prove that they listen during their hearings.

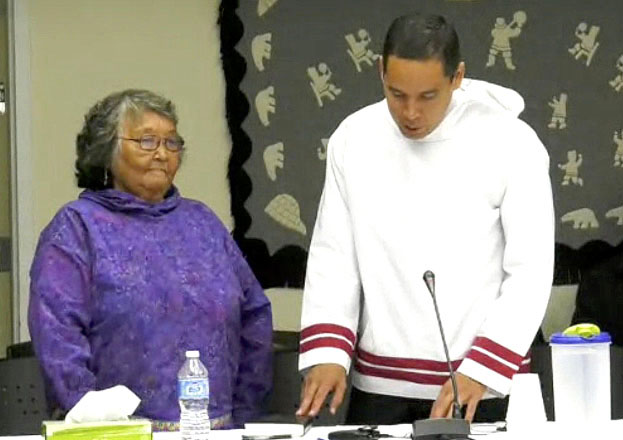

Progress keepers

And this week, the 186 federally recognized tribes that make up the Alaska Federation of Natives hold their annual convention in Anchorage. The three-day gathering, attended by more than 3,000 delegates, is, at its core, an opportunity to discuss issues of importance to the state’s Indigenous residents, but the involvement of lawmakers in Juneau and Washington ensures that what happens there gets discussed elsewhere.

Many of the convention’s events are unrelated to politics. An arts fair is a big attraction, as are dance and music performances. A number of local institutions hold events of their own to coincide with the gathering and is theme, the year: ‘innovation: past, present and future’. Among the events to be held this week, a discussion about education and a presentation about cultural appropriation are likely to be big draws.

Even so, the political element is likely to steal the show: The convention is taking place less than a month before the November 6 elections for national and state offices, including Alaska governor. This means some of the most widely watched and important events will be the debates between candidates.

The convention itself begins on Thursday, October 18, while a special elder-youth meeting will begin on Monday and wrap up in time to submit recommendations to the main event, ensuring, in the process, that the convention has what it takes to live up to its billing.

The Week Ahead is a preview of some of the events related to the region that will be in the news in the coming week. If you have a topic you think ought to be profiled in a coming week, please email ne**@ar*********.com.