What old caribou antlers in Alaska’s Arctic refuge can tell researchers about historic migrations

By analyzing isotopes in shed antlers, scientists can reconstruct how caribou moved across the North Slope in decades — and centuries — past.

The Gwich’in people of northwestern Alaska and northeastern Canada have a traditional name for the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge: “Iizhik Gwats’an Gwandaii Goodlit,” meaning “The Sacred Place Where Life Begins.”

Now a new study of the chemical makeup of discarded caribou antlers gives support to that traditional name, which is invoked in the Gwich’in campaign against oil development in the refuge’s coastal plain.

The study of caribou antlers discarded over past decades — and, in some cases, centuries — shows a longstanding fidelity among the Porcupine Caribou Herd to the coastal plain as a calving site.

Meanwhile, for animals from the Central Arctic Herd, which generally ranges to the west but also includes animals that use the refuge coastal plain for calving, the story is different, according to the study, published in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. Antlers discarded in the refuge by Central Arctic Herd caribou have a chemical fingerprint showing a marked change after the 1970s in landscape used in summer.

The shift in territory used by the Central Arctic Herd coincides with the start of North Slope oil development and production, said University of Cincinnati geologist Joshua Miller, the study’s lead author.

[Even after decades, caribou still aren’t fully used to oil development, scientists say]

“Notably, there is a big difference between what the herd is doing presently, in the last decades, compared to what they did in the past decades,” said University of Cincinnati geologist Joshua Miller, the study’s lead author.

The shift in territory used by the Central Arctic Herd coincides with the start of North Slope oil development and production, Miller said. It does not prove that oil development drove the shift, he said, but the correlation in timing is strong.

While the Porcupine herd’s summer range “stayed pretty stable,” the Central Arctic herd animals, as shown by the distribution of their antlers, have dispersed and expanded the territory that they use in summer, compared to past decades, Miller found. “It looks like habitat use was much more constrained prior to the 1980s,” he said.

The findings add to a body of scientific evidence showing that the Central Arctic herd — with territory that includes the heart of the North Slope oil operations and facilities — has changed its range and behavior in response to that industrial development. One recent study, for example, showed that Central Arctic caribou are demonstrating an aversion to oil facilities, avoiding close contact except when there is no option other than to pass through oil fields to reach coastal areas.

Pinpointing why the Central Arctic Caribou Herd changed its behavior may be difficult because its size has fluctuated widely. The herd numbered only about 5,000 in the 1970s — and was not even recognized as a distinct herd until then — but then the population expanded more than 10-fold, peaking at 68,000 animals in 2011 before declining again. The herd now numbers about 30,000, according to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

“A lot of things happened at the same time with the Central Arctic herd,” he said.

The history of the Central Arctic herd is invoked by both supporters and opponents of oil development in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge – with supporters pointing to the herd’s growth since the 1970s and opponents pointing to demonstrated oil-field disturbances. At issue is the effect of drilling on the Porcupine herd, which numbered 218,500 animals as of 2018, the most recent count.

[Researchers are watching the balance between Nunavik’s wolves and caribou]

Miller said his study of antlers shows a way to examine caribou behavior far into the past, to times before biologists were keeping track of populations and ranges.

His findings are based on the analysis of 65 antlers he and his colleagues collected in five field seasons in the refuge, where thousands of antlers have been dropped by female caribou over the past decades and centuries.

Each of the summers Miller was in the refuge, he and his research partners spend weeks camping in the refuge, floating on rivers and venturing into territory used by not just caribou but other animals like muskoxen.

The antlers he collected were analyzed for strontium, an element that can substitute for calcium in bones, including in antlers. Different geographic regions on the North Slope have different types of strontium.

The isotopes in strontium show what plants the caribou were eating and where those plants were located, he said. The underlying geology of the refuge coastal plain and the central North Slope area to its west are different, thus creating different chemistry in the plants that caribou eat.

“While tissues are growing, they are basically recording the plants that the animals are eating,” Miller said.

A limitation of his study was the geographic restriction of his work. Miller said. While some of the Central Arctic herd used the refuge coastal plain for calving, much of the herd does not.

“Of course, there’s lots of calving ground that we didn’t see outside the Arctic plain,” he said.

An important finding was that caribou antlers can show, through isotope analysis, herds’ movements from centuries ago.

The frigid temperatures of the refuge keep antlers intact for hundreds of years, with very little weathering, Miller found. The oldest specimen he collected dates back to the 1300s, attesting to the timelessness of caribou in Arctic Alaska.

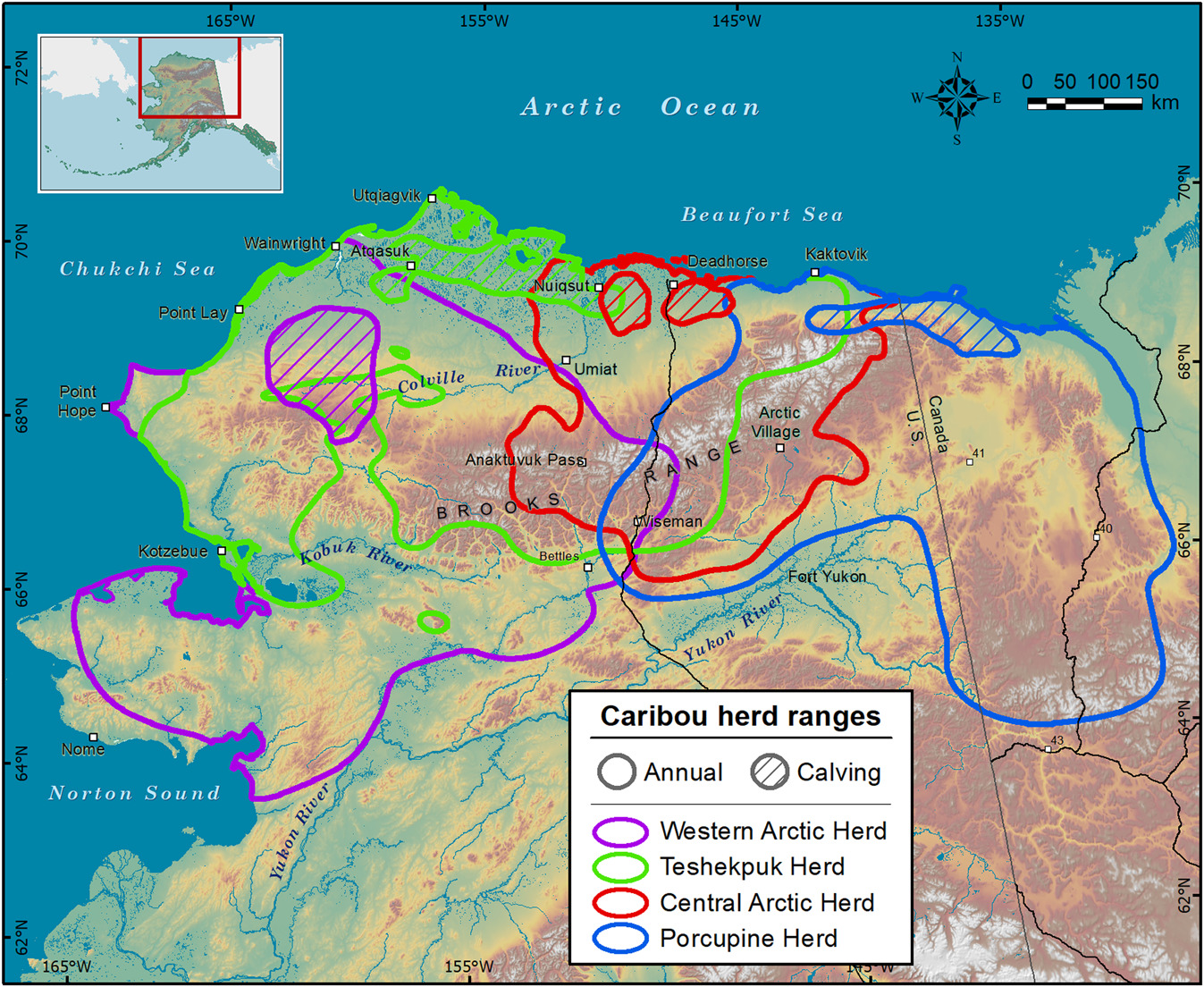

Miller said he hopes to expand the geographic scope of his antler analysis in the future. That could include work in the western part of Arctic Alaska, possibly examining migration patterns of the Teshekpuk Herd farther to the west — which uses a different area targeted for new oil development, the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska — along with more study of the Central Arctic herd.

While Alaska’s Arctic caribou herds generally have distinct calving grounds, recent research shows a lot of mingling on the North Slope. There is even an area used by all four herds — the Western Arctic Caribou Herd, most recently estimated at 244,000 animals, and the Teshekpuk Herd, estimated at about 56,000 animals, as well as the Central Arctic and Porcupine herds. The findings about herd mingling are detailed in a study published in August in the Journal of Wildlife Management.