When Boeing proposed the world’s largest plane for Arctic shipping

Climate change means a new plan to ship Alaska's Arctic gas to market by tanker is realistic — but pipeline alternatives have a long history in the state.

With climate change and the continuing decline in Arctic sea ice, a new proposal to export liquefied natural gas from Alaska in icebreaking tankers has become far more practical than anyone would have imagined even a half-century ago.

The Russian natural gas giant Novatek is already exporting LNG from the Yamal Peninsula by ship, so there is some precedent for the Alaska Qilak project now under discussion. It would operate year-round with icebreaking tankers docking 6 to 8 miles off the North Slope coast near the Point Thomson oil and gas field.

Climate change has certainly led to a change in the attitude that a gas pipeline — a project that faces many economic and political obstacles — is the only future option.

But in one sense, the discussion of non-pipeline alternatives for exporting Arctic resources is almost a replay of what happened a half-century ago.

While it’s true that several of the world’s largest oil companies were already thinking about an oil pipeline when Alaska’s giant oil strike happened in 1968, there were competing transportation ideas from the start.

In hindsight, most of the notions put forward were complicated, impractical or impossible, but unconventional ideas received at least passing attention because there was a degree of uncertainty about whether a pipeline would actually be built.

The idea of pipeline generated strong opposition at the time from environmental groups, which led visionaries, dreamers and inventors to suggest alternatives.

Oil had never been developed in a place like the North Slope of Alaska before and at first the technology to get it produced and shipped to market did not exist.

The most practical of the alternatives was to use icebreaking tankers to export oil. This idea received its grand test with the 1969 voyage of the S.S. Manhattan, a giant tanker, retrofitted to sail in ice, that became the first commercial vessel to travel the Northwest Passage.

The $40 million test was deemed a success, but the high costs were such that the tests demonstrated that icebreaking tankers would not be feasible on a large scale.

The Manhattan had to be removed from multi-year ice at one point by an icebreaker and on its second experimental trip, one of the ship’s seawater tanks was punctured by ice.

Before trans-Alaska pipeline construction began in 1974, however, there was no shortage of eccentric and outlandish ideas, ranging from dirigibles and elevated conveyors to a trans-Alaska tunnel and a monorail.

The tunnel “does not appear to present a viable alternative,” the U.S. Interior Department said in a 1972 environmental impact statement.

Bud Brown of Arizona proposed a “multi-purpose self-propelled aerial tramway system,” which would have a pipeline suspended from the towers.

In 1969, General Dynamics proposed that a fleet of nuclear-powered 900-foot submarine tankers be created and dispatched through the Northwest Passage.

Roger Lewis, president of the company, said each tanker could carry 1.2 million barrels on a route from Alaska to Greenland in about 35 days. From there the oil would be loaded onto regular tankers.

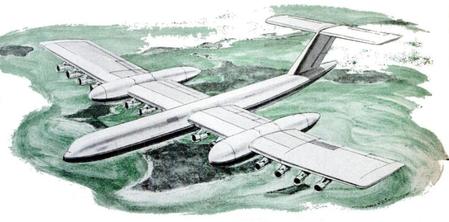

The most ambitious idea floated by a major U.S. company came from Boeing, which suggested using airplanes with 10 times the cargo capacity of a 747 to ship oil, natural gas and minerals from the Arctic.

The wing area on the design for the world’s largest airplane would cover more than three-quarters of an acre.

Boeing said the RC-1, the initials standing for “resource carrier,” would be powered by 12 jet engines and have 56 wheels on its landing gear. North Slope oil was to be carried in wing-mounted pods on the RC-1.

The plane never got off the drawing board.

The Interior Department wrote off most of the proposals that didn’t involve a pipeline, saying, “the various schemes generally have had little or no development and many ignore important Alaskan environmental conditions.”

In the end, the oil companies did not want to invest in alternative transportation technologies. They placed their bets on a pipeline that cost $8 billion and has been in operation for 42 years.

Dermot Cole can be reached at de*********@gm***.com.