Why domestic violence in the Arctic could surge with the coronavirus pandemic

Victims in remote, isolated communities in the Arctic already face limited resources for getting help. The pandemic is poised to make that even harder.

Around the world, rates of domestic violence and intimate partner violence are rising along with the spread of coronavirus.

Domestic violence often spikes during economic downturns and stressful times. Now, with the addition of national and regional lockdowns and new self-isolation and quarantine measures, many families may become trapped in abusive situations.

In the Arctic, where many towns and villages are extremely isolated, advocates fear this pandemic will bring with it an epidemic of violence as well — and that it will be much harder for those enduring abuse to seek help.

“The impact of this on victims is going to be probably a lot broader than we think,” Tami Truett Jerue, executive director of Alaska Native Women’s Resource Center, told ArcticToday. “We are really a vulnerable population for many reasons.”

[How the Arctic’s limited infrastructure could make coronavirus deadlier in the region]

In addition to their natural isolation, Arctic communities frequently have few resources for those enduring abuse or those who wish to break abusive patterns. Those suffering abuse frequently flee to the houses of family or friends, Truett Jerue said, but that may not be an option during this time of self-isolation and vulnerability to the virus.

And housing shortages across the circumpolar Arctic coupled with a lack of running water and sanitation in some communities can put more pressure on households.

The new shelter-in-place guidelines that many federal, state, local and tribal governments are adopting mean that more people are staying indoors, with children out of school and parents possibly out of work — which could result in rising tensions.

Jobs in Alaska, for instance, often depend upon tourism, fisheries or natural resource extraction — many of which are now seeing new restrictions because of the pandemic.

Add to that the high costs of living in the Arctic and no relief in sight for paying bills, and the pandemic could heighten existing issues “to a much more critical level,” Truett Jerue said.

“This is going to be one of those stressors that put some people over the top,” Truett Jerue said. “We haven’t touched even that little tiny fingertip of what I think is to come, in terms of the stress.”

The longer the pandemic and the accompanying economic downturn last, the worse the violence may be, she said.

Travel bans and self-quarantine rules

Many communities across the Arctic have locked down travel in light of the pandemic, often before the rest of their countries did so. Some communities are also prohibiting travel to neighboring villages.

But that makes travel out of a remote community more difficult than ever.

“Right now in Alaska, they’re tightening up even the rural travel into communities,” Truett Jerue said. This week, for example, Alaska’s main rural air carrier announced that it was shutting down abruptly.

“Trying to get someone to a regional shelter could be really problematic as well, because the planes aren’t going to be running regular schedules, and they may not be taking passengers unless it’s an emergency,” Truett Jerue said.

And, she said, an abusive situation might not be seen as a medical emergency — at least, not until it’s too late.

Even if an abuse survivor is able to make it to a shelter in one of the hub communities in Alaska, like Nome or Kotzebue, those shelters were already near capacity before the pandemic.

“They’re all trying to put isolation rooms in their shelters, but they’re already overcrowded,” Truett Jerue said.

Requirements for 14-day self-quarantines after travel, as well as ongoing physical distancing, would be difficult or even impossible to observe.

“The safety of our staff, and the safety of other residents, has to be taken into concern when you look at shelter living,” Truett Jerue said.

Some shelters, like the Abused Women’s Aid in Crisis center in Anchorage, previously needed to expand. AWAIC broke ground on their expansion last fall, aiming to go from 52 to 67 beds.

But in the meantime, it’s already full. Although AWAIC often operates over capacity, demand is at an “all time high,” Anchorage Daily News reports.

“All of us that are doing this kind of work are really trying to kind of get ahead of it, trying to come up with solutions around all of what this means,” Truett Jerue said.

More resources needed

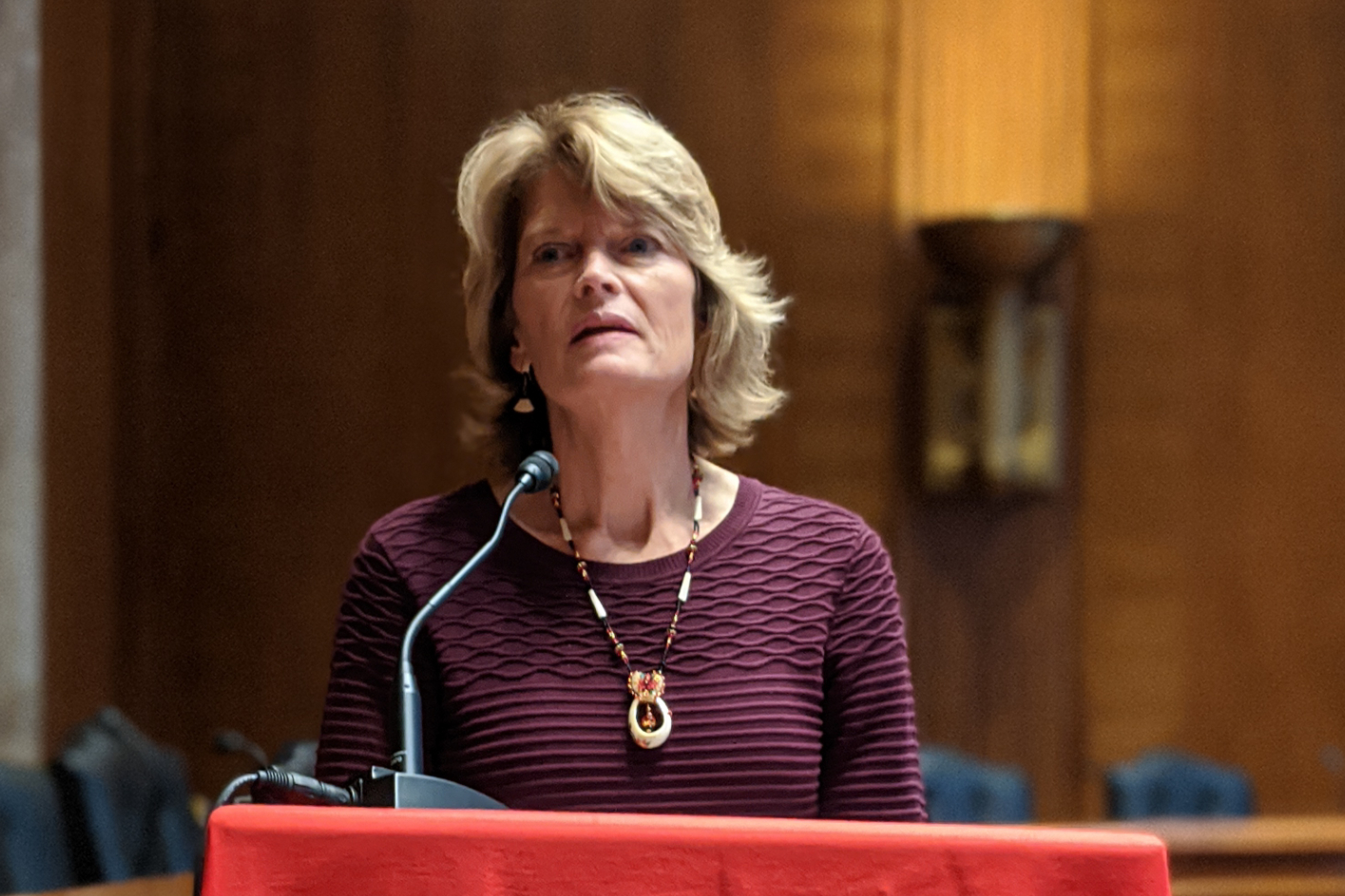

On March 23, U.S. senators Lisa Murkowski, a Republican from Alaska, and Amy Klobuchar, a Democrat from Minnesota, called for additional resources to battle rising rates of domestic violence.

“An unintended but foreseeable consequence of these drastic measures will be increased stress at home, which in turn creates a greater risk for domestic violence,” they wrote.

Previously, Murkowski co-introduced Savanna’s Act and the Not Invisible Act, along with Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto, a Democrat from Nevada, both intended to curb the epidemic of violence against Indigenous women and girls. The bills passed the Senate unanimously on March 11.

Alaska has one of the highest rates of intimate partner violence in the United States. Half of women in Alaska experience some form of violence in their lifetimes, and the numbers are even higher among Alaska Natives. More than 84 percent of American Indian and Alaska Native women experience violence during their lifetimes.

Alaska also has the highest rate of women murdered by men. Among Alaska Natives, the rate is three times that of their non-Indigenous peers. Murder is the third-leading cause of death among Indigenous women in the United States, and Alaska has one of the highest rates of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in the country.

In February, Murkowski also co-introduced a bill to prevent human trafficking, a growing problem in Alaska and across the North. The pandemic — and the attendant economic downturn — could increase trafficking throughout the Arctic.

A major part of these pieces of legislation concerns law enforcement: improving data collection, coordinating across agencies, reopening unsolved cases. Cold cases and a backlog of samples have mounted in Alaska, with some survivors waiting decades for progress on their cases.

Meanwhile, the high rates of physical and sexual violence in the Arctic are compounded by limited and under-funded law enforcement in the region.

About one-third of Alaska villages have no law enforcement at all. Communities with no police officers and no road access have about four times as many sex offenders as the rest of the country.

In other places, the system is teetering on the brink of collapse, with few resources to investigate crimes or assist victims. Some village police officers earn as little as $10 an hour, an investigation by Anchorage Daily News and Propublica found last year.

The investigation also revealed that dozens of criminals were hired as police officers in remote villages — including Stebbins, Alaska, where all seven cops have been convicted of domestic violence in the past 10 years.

Last June, the Department of Justice announced emergency funding to address the public safety crisis in rural Alaska. The state of Alaska also announced planned changes to the system at the end of last year.

But with attention and resources now directed at the coronavirus pandemic, these changes may be slower than planned.

Even when police officers are present in Arctic communities, they may perpetuate inequity within the system, making it harder to break patterns of abuse.

In Nunavut, for instance, Inuit women are frequently the targets of “racialized policing,” according a January report on gendered violence against Inuit women.

Women reporting domestic violence are routinely dismissed by police and sometimes removed from the abusive situation, instead of having the abuser removed, the report said.

Yet in Nunavut, women are 13 times more likely to be victims of violent crime and 12 times more likely to be sexually assaulted than their Canadian peers.

Women across the Canadian North must travel the longest distances in the country to find shelters.

Inequity spanning the Arctic

At the Arctic Circle Assembly in Reykjavik, Iceland, last October, several leaders and advocates discussed domestic violence and gender inequality.

“Gender equality has been almost absent as a topic in the governance of the Arctic,” said Eva Maria Svensson, deputy head of the department of law at Gothenburg University in Sweden. And when it is spoken of, she said, “there is actually a huge gap between the rhetoric on gender equality and the outcome.”

In northern Sweden, there’s a complete lack of resources, including counseling, for those suffering domestic violence among Sámi communities, one report says. Official documents — including police reports — are rarely translated into Sámi language.

In Norway, nearly half of Sámi women and one-third of Sámi men said they’ve experienced some form of violence in their lifetime, rates higher than their non-Indigenous peers. Yet Sámi victims of violence are less likely to go to the police, a report found.

It’s difficult to find statistics from Russia that separate out its Arctic regions. But between 5,000 and 7,000 women suffer domestic violence each year nationwide, and almost 2,000 children have been killed by family members, according to the police. Yet Russia still decriminalized first-time offenses of domestic violence in 2017.

Even before the pandemic, the Arctic was already undergoing political and environmental changes. All of these changes can put pressure on existing inequities, including violence, in the region.

“The changes in the Arctic, they affect everyone — but they don’t affect everyone in the same way,” Hjalti Ómar Ágústsson, project manager for gender equality in the Arctic at the Icelandic Arctic Cooperation Network.

Iceland, the country closest to reaching gender equality in the world, has one women’s shelter for the entire country. One in four women in Iceland have been sexually or physically assaulted.

Sara Olsvig, chair of Greenland’s Human Rights Council and head of UNICEF Denmark’s office in Greenland, urged advocates to continue focusing on the rights of the marginalized — including Indigenous women and children — in light of these rapid changes.

“Whenever the society is changing that drastically, as we are seeing in our homeland, we must be even more aware of our rights,” Olsvig said.

Violence against women is “extreme” in Greenland, she said. About two-thirds of women in Greenland have experienced or been threatened by violence, and girls and women also face very high rates of sexual and physical abuse. In Greenland, nearly one in three children have been abused — rates about nine times higher than in Denmark and Norway.

In search of solutions

On March 29, Greenland temporarily banned alcohol in Nuuk and in two other communities in southwest Greenland. Martha Abelsen, Greenland’s minister for health, social services and justice, said that “domestic violence has been on the rise in recent weeks” in Nuuk.

According to a statement from the government, “the coronavirus situation and especially the closure of Nuuk are pushing families who are already challenged.”

“The government wants these women and their children to get the help they need, so they have a safe place,” Abelsen said in the release.

Last week, Cambridge Bay in Nunavut also banned alcohol for two weeks due to coronavirus concerns. Nearly all calls to the local police were related to alcohol, the mayor said.

Some communities in Alaska have also looked into banning alcohol, Truett Jerue said, but so far they have run up against tribal and state sovereignty issues.

The high rates of violence in the circumpolar North have been compounded both by “the lack of services that could possibly help people make different choices,” said Truett Jerue.

This pandemic could limit those services even more.

“We already face so much disparity in getting services for victims, particularly of domestic violence or even sexual assault,” Truett Jerue said.

“And now we have other challenges that are going to create a bigger disparity.”