Why Russia’s thawing permafrost could speed up global climate change

If Siberia's permanently frozen soil continues to melt, the impact of released greenhouse gases will be felt around the world.

MOSCOW — As vast expanses of Siberian permafrost have been thawing amid an overall rise in annual temperatures, greenhouse gases are being released into the atmosphere, threatening to further expedite climate change on a global level.

Permafrost spans northern Russia, containing deposits of carbon matter for thousands of years. When thawing, such soil can release carbon-based greenhouse gases, such as methane.

Scientists are concerned that a thaw could be occurring on a massive scale.

“We are currently observing a very rapid course of certain thawing processes,” Mathias Ulrich, a geographer and permafrost expert at the University of Leipzig, says.

“Large amounts of carbon are contained in the permafrost, probably about twice as much carbon as is currently present in the atmosphere,” according to Ulrich. There is a potential for “enormous greenhouse gas emissions, which in turn would exacerbate current global warming.”

Two of the world’s hottest years in recorded history took place in the past five years, with temperatures in 2019 second only to 2016, according to the World Meteorological Organization.

“Since the 1980s each decade has been warmer than the previous one,” the organization said in a report. “This trend is expected to continue because of record levels of heat-trapping greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin has called for the country to undertake measures to prevent global warming during a nationally televised press conference two months ago.

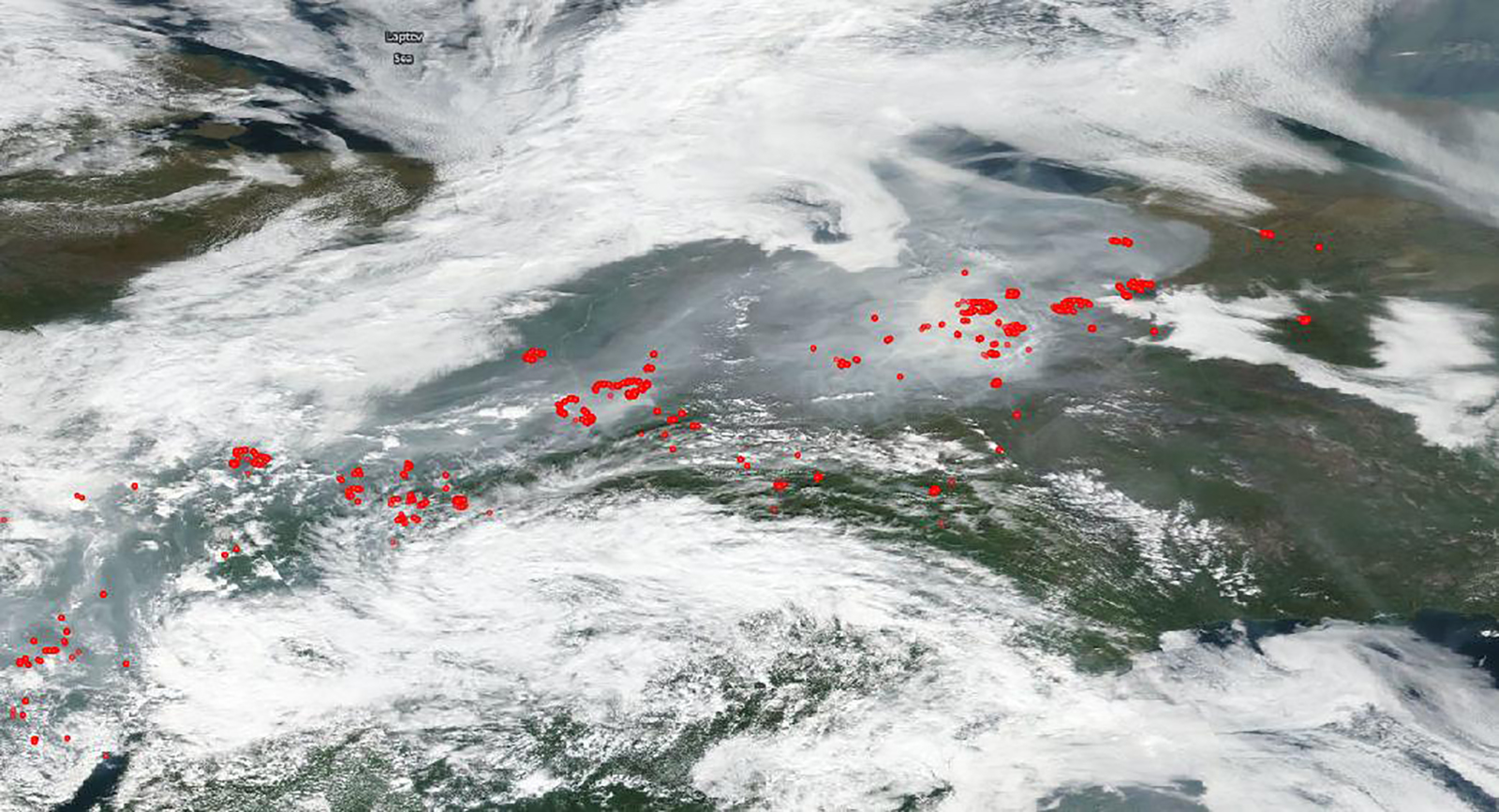

Russia, the world’s largest country by territory, is warming at a rate more than twice as fast as the global average, according to Putin. The temperature rise has led to increased wildfires and flooding, among other consequences, he has warned.

Russia’s Environment Ministry provided a similar assessment in a report a few months prior, saying the past four years have been the hottest since global temperatures have been recorded.

Growth of greenhouse gas concentrations is one of the key factors driving climate change, the report said.

“In many respects, the existing permafrost models are currently slower in their response to warming than the reality of the observations shows us,” says Guido Grosse, a permafrost researcher at the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research.

If large quantities of greenhouse gases are released, the goal of limiting global warming to an acceptable level would be even more difficult to achieve, according to Grosse.

The United Nations Environment Programme has also warned of a possible domino effect.

Last month scientists from Russia’s Tomsk State University, together with colleagues from other countries, determined that the average annual temperature in Siberia had risen by almost four degrees Celsius in the past 50 years.

Yelena Parfyonova, a researcher at the Russian Academy of Sciences, has estimated that if greenhouse gas emissions are not reduced, the permafrost area could shrink by 25 percent by 2080.

Melting permafrost also poses a threat to cities in such regions, Grosse said.

“With the defrosting of ice-rich permafrost, any infrastructure — buildings, roads, runways and pipelines — is damaged or is massively more expensive to maintain.”